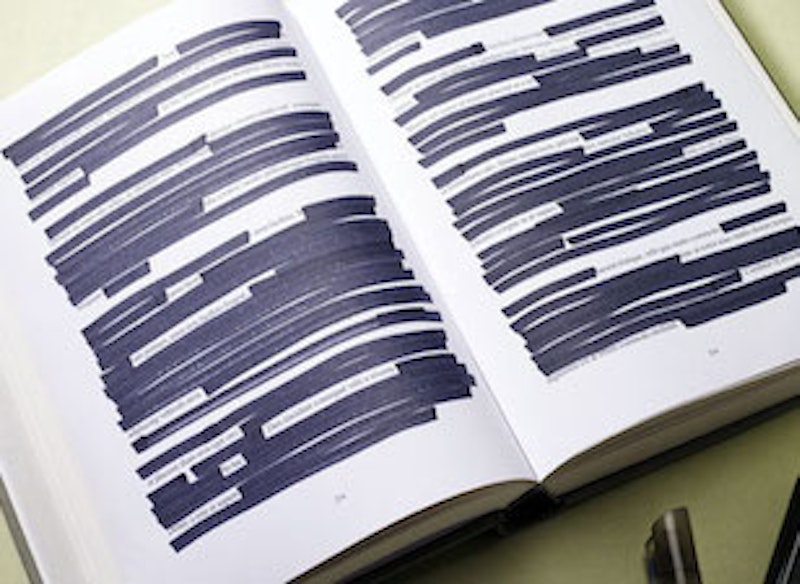

Much has been written about the Trump administration’s reshaping of the American judiciary, but surprisingly little has grappled with what a rightward tilt to the courts might mean for freedom of speech. People forget, perhaps, that the United States has a history of censorship. Reading Censored: A Literary History of Subversion & Control, the recent book by Matthew Fellion and Katherine Inglis, it’s clear how near that history is. And how easily it might be revived.

The form of Censored is a series of overviews, in 10 pages or thereabouts, of notorious censorship cases. Most are about works of literature, beginning with the history of unauthorized English translations of the Bible and moving forward chronologically at a smart pace; the second half of the book deals with cases from roughly the past 100 years. Themes emerge over time, a history of censors and crusaders and publishers, as the cast of characters who fight over one book may return for another fight a decade or two later. Issues recur within a specific legal tradition; all the examples in the book are from the United States or United Kingdom, with one look at a case from Ireland.

The US and UK become contrasting examples of approaches to censorship within a broadly similar legal tradition: similar tests of obscenity, in particular. The introduction briefly considers expanded definitions of censorship some have suggested for the contemporary world—in which private businesses like search engines can be seen as vehicles for censorship—while an afterword sums up the book’s idea of what censorship should be understood to mean: a kind of repression deriving from a power imbalance, necessarily something inflicted on the less powerful by the more powerful. (Which is one reason, argue Fellion and Inglis, why university protests can’t be considered censorship.)

Some of the cases the book examines lead to discussion of various principles about the boundaries courts have drawn between freedom of expression and the power of authorities—prison authorities, for example, or school authorities. Here, as elsewhere, the book is on the whole clear, moving quickly over complex issues. Sometimes perhaps too much so; there’s a funny story about Bennett Cerf fighting the censorship of Ulysses in the United States that the book ignores.

Briefly: Cerf, who wanted to publish an edition of Ulysses in the 1930s, had to import a copy of the book from Europe and have it seized at customs in order to bring it to trial to convince a judge that it wasn’t obscene. He had a copy specially prepared, pasting in reviews that hailed the book as a modern classic. But when his agent brought it to customs, the customs inspector waved him through without checking his luggage. Cerf’s agent had to tell the inspector he thought there was contraband material in his bags, and direct the baffled inspector where to search. “Aw, hell,” said the inspector when he found the book, “everybody brings that in,” and again tried to wave the man through. This is relevant as a reminder that before Ulysses was established as a fundamental text of 20th-century literature, it was read as an underground dirty book.

In fact, it’s interesting to observe the reasons the books discussed in Censored were suppressed. Many of them are now regarded as classics (Ulysses, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lolita, Huckleberry Finn) or as critical in their fields (The Well of Loneliness, EC Comics). All of them made somebody uncomfortable, usually in some way to do with sexuality. Sometimes it was due to direct ideological or political reasons, as in the first English Bibles. But either way, in the story Censored tells over and over, authorities argue that some test established as precedent shows that a given book tends to deprave or corrupt. Inevitably the test also finds important works of literature occasionally also obscene.

Censoring a book, in short, raises some philosophical questions. Most people who think that dirty books are bad also think that very good books in some way dilute anything dirty in them. What’s strange is that these assumptions go largely unquestioned and unstated in legal cases. There’s a recurring fiction here, that the utility of books and the effect of fiction can be decided clearly.

That fiction, the argument for censorship, is always implicitly in conflict with the values of a democracy. If people’s behavior can be reliably programmed by texts, what’s the point of letting people vote on anything? They’ll just vote according to how they’re programmed. Of course reading a book changes someone, but the question is whether that shape can be predicted. Censors think so, or at least believe that various elements of the population (women, children, the lower classes) are uniquely vulnerable to the malign influences of texts. And yet, with Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover at large in the world, nations haven’t yet collapsed due to any obvious influence of these novels.

One might wonder if the reasons for censoring these books are what the censors say they are. Did Lady Chatterley’s Lover annoy the authorities of its day because there was sex in it, or because it implied that men were immature about sex? Or because it had a subversive view of World War One?

In this case, as other obscenity trials, authorities read out passages of the text even though the legal doctrine they were working with insisted that books could only be banned for a general theme, not specific passages. One must, perhaps, be open to the possibility that censors have especially dirty minds. But then censors must repress what they cannot bear to have spoken openly, and be open about sex and alternative ways of performing sexuality is also to be open about alternative ways of constructing society.

Conversely, then, more than being about sex, censorship’s about conformity. Fanny Burney’s father kept her from staging her play The Witlings because in the 18th century it was improper for women to do that sort of thing. The mere concept of homosexuality led the United Kingdom to censor The Well of Loneliness. Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza was censored in a New Mexico high school and the school’s Mexican-American studies program was shut down because what was being taught was too disturbing to the authorities—however historically accurate.

Censored is a book about power; about those with power trying to enforce their view of reality and morality on those with less. It’s smoothly written, and presents the development of two different legal traditions defining freedom of the press. It brings out the psychological stress so often involved in censorship. Freud was not wrong about everything, and the desire to repress writing is often a symptom of a broader neurotic desire to repress an awareness of reality. Fear of sex is a symptom of a fear of mockery, and the realization that the mockery is justified. Let D.H. Lawrence, in his own much-censored book, sum up what Censored shows us: “In fact everything was a little ridiculous, or very ridiculous: certainly everything connected with authority, whether it were in the army or the government or the universities, was ridiculous to a degree. And as far as the governing class made any pretensions to govern, they were ridiculous too.”