I’ve just read John Higgs’ latest book, William Blake vs The World, for the third time in a row. It’s not often I’m so impressed by a book that I get to the end and promptly start all over again. It’s only happened with a few books in my life. Another was Witness Against the Beast by EP Thompson, also about William Blake. It’s worth comparing the two books.

Thompson’s book is an exposition of an idea first suggested by AL Morton in his 1958 work The Everlasting Gospel, that Blake was an antinomian: that he was from a tradition dating back to the English Civil War, characterized by such lost and forgotten groups as the Ranters and the Diggers. “Antinomian” means “against the law.” As a historian, Thompson identifies one particular group whose ideas bear some resemblance to Blake’s, the Muggletonians, and suggests some direct connection between them. Was Blake a Muggletonian, he asks?

Recent scholarship has rejected that idea, but it seems to me that this is a profound misreading of Thompson’s work. While the last quarter of Witness Against the Beast is an exploration of this strange, forgotten sect, which somehow managed to survive into the 20th century, the bulk of his book is about the parallels between the antinomian tradition—the English Dissenting, or English Radical Tradition, as it’s known—and the writings of William Blake; and it’s clear from the context and the language that there are such links.

Was Blake a Muggletonian? No. But the echoes of Civil War antinomian and dissenting thought were still extant in London during Blake’s lifetime, and it’s hard not to imagine that he wasn’t influenced by them. If we were to ask how those ideas survived for such a long period, from the 1640s to the 1750s, let’s remember that two of those strands are still in existence in the present, in the form of the Baptist Church, and the Quakers, both of whom were considered extremely radical in their day.

When I first read Thompson’s book, I identified strongly with the tradition he was describing, which began a process of exploring some of those ideas. It explained why Blake continues to have such resonance, and why, from the first time I read him, I became obsessed. I’m not the only one. The point about Thompson’s book is that it was written, not by a Blake scholar or a biographer, but a historian, and it takes a completely different approach to most previous books on the subject.

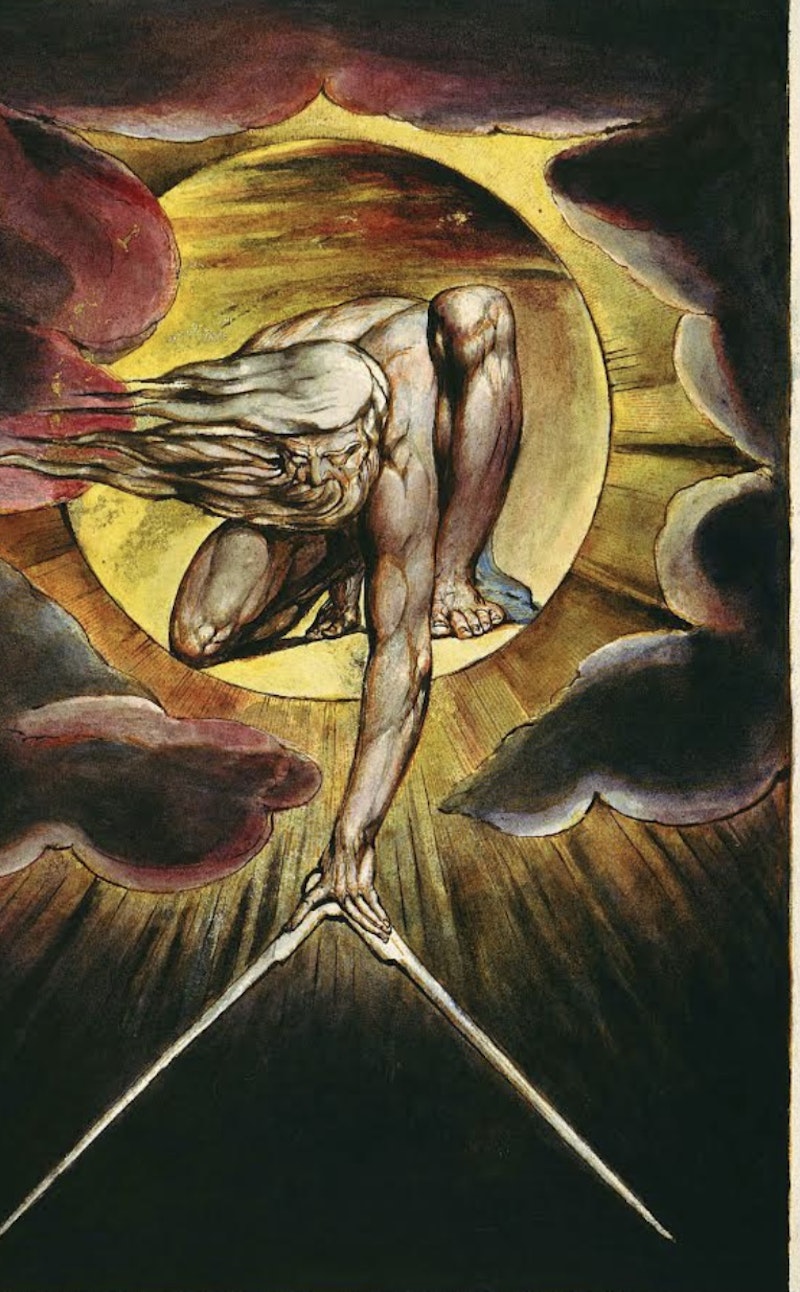

The same is true of Higgs’ book. Higgs is not a Blake scholar. He’s not a historian and his book isn’t literary criticism. It’s not biography, although it does contain elements of all these things. Rather, it’s an explanation, an exploration, a way of approaching Blake that makes him relevant to our own lives. Higgs’ book is as much about us as it is about Blake. If the book does contain biographical elements (how could it not?) it’s also the biography of one of Blake’s central characters, Urizen. You’d recognize him. He’s the subject of one of Blake’s most famous prints. Picture him. He’s naked in a circle of light, leaning down with a pair of compasses to measure the Earth below. His white hair and beard are blown sideways and he’s surrounded by dark, ominous clouds. He’s called The Ancient of Days.

This is Urizen, an image that originally appeared in one of Blake’s prophetic books, Europe a Prophesy, and which he recreated at intervals throughout his life. You’d probably imagine him as a representative of God. As Blake said in his later book Milton, “Urizen is Satan.” This would probably have come as a great surprise to the custodians of St Paul’s Cathedral, on whose dome an image of Urizen was projected during the Blake exhibition at the Tate in 2019. I wonder if they would’ve allowed it had they realized who Blake himself identified the image with?

There are different interpretations of what the name “Urizen” means. Probably a combination of “your horizon” and “your reason.” Urizen is the representative of rational thought, and is echoed again in another famous Blake image, of Newton sitting on an antediluvian rock, leaning down and measuring out geometrical shapes onto a roll of paper. Newton is absorbed in his task; so much so that he’s unable to appreciate or even acknowledge the astonishing beauty of the world in which his focused study takes place.

Here is Higgs’ description of the character: “Urizen is the personification of reason. He is the intellect that creates law, he is controlling and associated with language, and it is he who constructs the human-scale world of rationality and logic in which contrary positions cannot both be physically true. Urizen is the conscious observer that forces Schrodinger’s cat to become either alive or dead.”

The reference to Schrodinger’s cat tells us where Higgs is going to take his story. Higgs is first and foremost a student of Robert Anton Wilson. He takes a similar approach. His book ranges over a wide variety of subjects, taking in quantum mechanics, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, culture and theology in a way that links these disparate elements together into a coherent narrative.

Urizen is central to Higgs’ book, as he is to Blake’s work, because Urizen is central to us. He is us: us as we appear to ourselves. Us as the story of our lives which we construct and reconstruct on a daily basis. Us as the default mode network, the top-down, rational model of the Universe we carry around in our heads, which allows us to navigate around our world efficiently but which, as Higgs describes it, “cauterises chaotic imagination.”

Urizen is the ego, the creator God who made the world in his own image. Blake’s entire output is about rebalancing the world, recreating it in the imagination, liberating it from the limitations of one-dimensional thought and returning us to the visionary world from which we came, and which Blake himself still inhabits.

It’s this that makes Higgs’ book so useful. He wrests Blake out of the hands of the academics and returns him to the people, where he belongs. He shows us how relevant Blake’s vision is in this time of crisis and confusion, and how crucial it is for all of us to try to see the world the way Blake saw it, not as “the single vision” of “Newton’s sleep,” but in all its multifaceted, dynamic, imaginative, psychedelic, multidimensional, visionary glory. Reading Higgs’ book is one step towards experiencing that world again.