A man measures his life by what he's done, but it's the things left undone that haunt him.

I sit here at my desk, feeling somewhat pleased with the words I've put down on paper. Maybe it's a column for UnHerd, an obituary for The Ringer, or just another white paper for the consultancy that pays most of my bills. I lean back in my chair, adjust my size-eight thinking cap, and imagine I've really accomplished something. But have I?

I've churned thousands of bylines—hundreds just for Splice Today, which is my de facto home base. I've lifted weights that would make most men's knees buckle. I've taught law and history to college kids and argued cases in court. I’ve ascended Vancouver’s Grouse Grind not just twice but thrice. But what about all the stuff I haven't done?

I knew a guy once, a big-time professor in his emeritus phase. He'd pound out his final monograph on an old Underwood, churning out copy like a machine. Every afternoon he'd leave the office feeling like he'd conquered the world. His CV was stuffed. But one day, he pulled me aside and talked about the monographs he never wrote.

"Oliver," he said, "you ever think about the things you can’t get to? I’m 83 years old, and I wrote six books—that’s it. Six. How many books have been written? And then—how many haven’t?"

I replied with some cliche along the lines of "that way madness lies." But he had a point.

No matter how much you do in this life, there's always more you didn't do. It's like trying to empty the ocean with a teaspoon. You can scoop out water all day long, feeling mighty proud of yourself. But the ocean's still there, vast and unconquered.

I once interviewed the great bodybuilder Frank Zane after he'd retired. Here was a guy who'd done it all—set records, won championships, had a wonderful marriage with a woman he loved. But you know what he talked about? All the contests he didn’t win. The shows he should have won. The what-ifs and the could’ve-beens. He wasn’t sad, merely philosophical. He won the Mr. Olympia three times, but he also lost a few times when it counted—most notably 1980, when Arnold Schwarzenegger came back and beat him. Was that all there is?

It's not just the big shots, either. Walk into any gym in this city and you'll find guys talking about the lifts they never attempted. The competitions they never entered. The records they never broke. We're all carrying around the weight of our unfinished business. The risks we were too scared to take.

I knew another bodybuilder, not a legend on the order of Frank Zane but a real go-getter type nonetheless. He was always hustling, always working an angle. Made what he claimed was a fortune selling steroids by the time he was 40. You'd think a guy like that would be satisfied, right? Wrong.

"Why the long face?" I asked him. "I thought you were on top of the world, selling all those worthless powders and pills."

He shook his head. "It's the pits, Oliver. I just spent a mint to cut a deal to stay out of prison on some drug charges. Turns out all those supplements I was pushing weren't exactly FDA-approved."

See, that's the thing about success in this game. It shows you how much more there is to achieve. But it also shows you how far you can fall. It's like climbing a mountain. You struggle and sweat and finally reach the summit. But when you get there, you realize the climb down can be just as treacherous. One wrong step, one bad decision, and you're tumbling all the way back to the bottom.

"For every good deal I made," he said, "there were a hundred I passed on. For every lift I hit, there were a thousand I didn't attempt. I could've been so much more." But more to the point, he could've been so much less. A number in a cell block, forgotten by the world he once dominated. That'll get anyone down.

Writers have it worse than most, though. We're cursed with imagination. We can picture all the stories we haven't told, all the characters we haven't brought to life. It's enough to drive a man to drink. Or in my teetotaling case, to do more deadlifts. You finish a piece of writing and for a moment you feel satisfied. Like you've captured something true and important. But then you look out the window and see the whole world going by. All those lives and stories you'll never know, never tell.

But you can't throw in the towel. You keep writing, keep lifting, keep teaching. Because what else is there?

My dad’s best friend was an old alcoholic used car dealer who’d been in the game for six decades. His hands shook so bad he could barely write up the orders, but he still came into his little trailer office every day. I asked him why he didn't call it a career, enjoy his golden years.

He looked at me like I was simple. "And miss when somebody walks in to buy me out of this shithole so I can finally retire? No way."

The big sale is always just around the corner. The big lift is always the next one. The best is always yet to come. It's like trying to describe one of my workouts. You can talk about the weights, the reps, the sweat. But you'll never capture it all. There's always more beneath the surface, more weight that could be added to the bar.

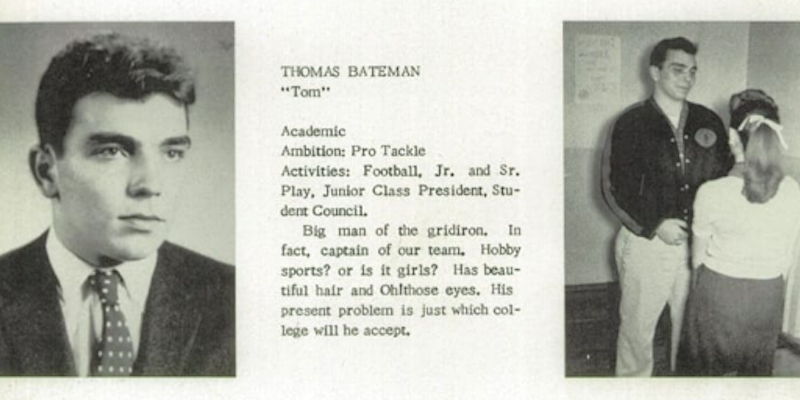

I once asked my old man if he regretted not making it to the NFL—the professional goal he had set for himself in his high school yearbook. He just laughed.

"Son," he said, "I captained the WVU freshman team. I started as a sophomore, right after West Virginia had some of its best teams ever—Sam Huff and Bruce Bosley and those people. How many guys can say that? Yeah, I never made the pros. My ACLs gave out on me. But I played the game at a high level. I was in the mix. I knew I was as good as those other bums. That's enough for me."

Maybe that's the secret. Not to worry about all you haven't done, but to appreciate what you have done. To know that every snap you played, every block you threw, every yard you gained, is a victory against the vast silence of the universe.

My old man was there. He was close—very nearly tapping the source, almost tasting the big time. And even with the injuries, even with the what-ifs, he found satisfaction in that.

I'll never write the great American novel. I'll never set an all-time powerlifting record. I'll never argue a case before the Supreme Court. But I can write my stories. I can lift my weights. I can do my work. And maybe that's enough.