Manhattan, Manna-hata, the Algonquins’ “island of hills,” 40 degrees north latitude, 76 degrees west longitude, is 12½ miles long and 2½ miles wide at its broadest point. Every day, 1.5 million people ride its buses and 3.5 million its subways. Each fare was $2.75 when my wife and I left the city for New Hampshire.

But 59,000 commuters now ride free on the Staten Island ferry. Vince Sweeney, a Staten Island historian, defines a ferry as a function rather than a boat: water-borne transportation regularly crossing some body of navigable water for the conveyance of persons, vehicles, and animals. The first Staten Island ferry of which we know started in 1708. It ran between William St. in Manhattan and the Watering Place (now Tompkinsville) on the east shore of Staten Island. Oarsmen powered the first ferries. Later, someone devised a horse-driven treadmill to propel the boats.

In 1810, Cornelius Vanderbilt, a handsome, profane Staten Islander, borrowed $100 from his mother to run a ferry from Stapleton, another east shore town, and the foot of Whitehall Street. Seven years later, he launched the first steam ferry, the Nautilus, and charged an extortionate 25-cent fare—children half price. By contrast, the nickel fare was sacrosanct for most of the 20th century, rising to 25 cents and then 50 cents only under pressure of the city’s fiscal crises. Then, on July 4, 1997, Mayor Giuliani decreed there would be no more fare: just in time for that year’s mayoral elections.

For five years, five mornings a week, I walked to the ferry terminal in St. George, Staten Island to catch a ferryboat. From its bow, Manhattan’s towers gleamed on the horizon like the fabled City of Cibola, or El Dorado, or like a vision of the City of God. The boat rumbled from its slip: a flock of “the pitiless, the eye-pecking gulls” gathered astern to wheel and soar, serene and observant, over its bubbling wake. Then, as the boat passed the great bronze statue on Bedloe’s Island, the opening lines of Hart Crane’s “The Bridge” suddenly made sense:

How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him,

Shedding white rings of tumult, building high

Over the chained bay waters Liberty—

My paternal grandfather saw the same statue from an immigrant ship in 1906. He was then an 18-year-old adventurer who’d escaped conscription into the armies of the Czar by crossing the border into Austrian Poland beneath the load in a manure wagon. He had thence made his way through Austria, Germany, and Belgium (where he quickly picked up a sound idiomatic French, which he could speak well into his ninth decade), to England, whence he sailed from Southampton.

Within a century of his arrival, his experience—of a long sea passage, closing with the vision of a mighty woman, “her lamp the imprisoned lightning”—has become uncommon, if not unknown. Men and women no longer come here in steerage. They land from airplanes, something of which my grandfather probably had no knowledge in 1906, a practical technology even now barely a century old. Crane writes:

O sinewy silver biplane, nudging the wind’s withers!

There, from Kill Devil Hill at Kitty Hawk

Two brothers in their twinship left the dune;

Warping the gale, the Wright windwrestlers veered

Capeward, then blading the wind’s flank, banked and spun

What ciphers risen from prophetic script,

What marathons new-set between the stars!

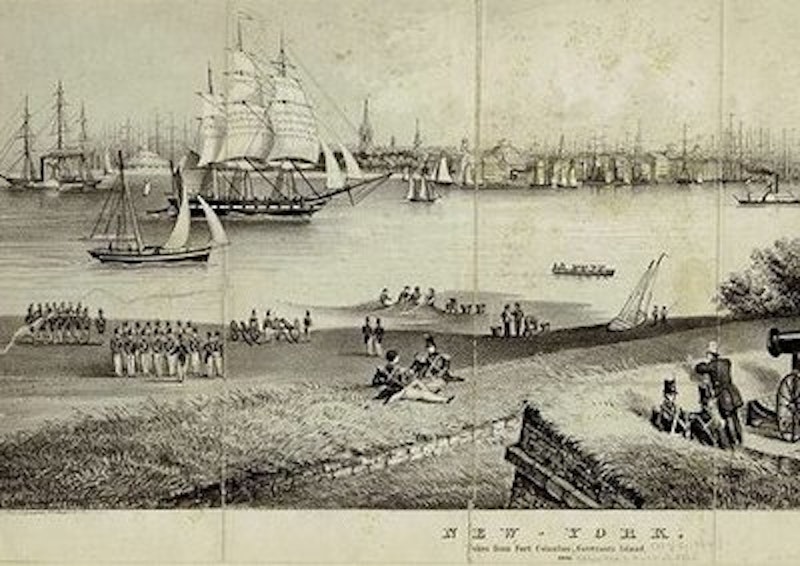

So, too, we have changed how we carry freight across the seas. Now the great container ships glide past St. George to Elizabethport and the Bay of Newark, where the containers stand stacked for transfer to train and truck. Of the hundreds of ships that once daily lined Manhattan’s shores with a forest of masts, only a few cruise liners now swing at anchor.

At Whitehall in Lower Manhattan, swift currents and contrary winds bumped my boat into its slip. Nearby, a pile driver alternated puffs of steam with hammer blows as it drives a wooden pile into the harbor floor. It was probably the last working steam-powered machine in Manhattan, if not the city. Nothing more surely measures progress than the obsolescence of steam, the driving force of the Industrial Revolution. The city’s last steam locomotives, the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal Railroad’s oil-burning switchers, serving the waterfront north of the Navy Yard, dropped their fires in 1962; the last steam ferryboat, the Verrazzano, stopped all engines in 1981.

New York’s older than Philadelphia or Boston, yet only a handful of pre-Revolutionary buildings have survived (St. Paul’s Chapel, on lower Broadway, is the only one in Manhattan). Walking uptown, I often unfairly contrasted the city with John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Colonial Williamsburg. Manhattan’s past exists side-by-side with the present, and though fragmented, often remains oddly alive. Williamsburg was barely a ghost town when Rockefeller began restoring what had been Virginia’s colonial capital. Today, the hamlet is beautifully restored and maintained. It presents a careful, corporate, and inoffensive vision of colonial history. I think then of Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic, a funny, insightful book, which describes how an Alabama school district avoided offending anyone over the War Between the States by dropping it down the memory hole: their history curriculum began after the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

Downtown’s tortuous, irregular streets are those laid out by the Dutch and the English—except Broadway, which was an Indian trail running north from the Battery before the white men came. Some street names have changed, usually for political reasons: Crown St. was renamed Liberty. But most remain the same. The indispensable AIA Guide to New York City notes that “Pearl Street was once the edge of the island where mother-of-pearl (oyster shells) littered the beach… Wall Street, the most famous, was the site of the northern boundary of New Amsterdam, where a wall was erected against the English and the Indians.” Of course, there have been no beavers on Beaver St. for nearly 300 years. One wonders about Maiden Lane.

Nor has anyone played bowls in Bowling Green, the city’s oldest park, since the end of the 18th century. In 1771, the royal government erected a gilt-bronze equestrian statue of King George III and a black iron fence with ornamental crowns. After the first reading of the Declaration of Independence on July 9, 1776, up at the Commons, just south of today’s City Hall, a mob of Patriots came downtown, toppled the statue, and broke off the crowns. The statue was broken up and carried away and melted for shot. A fountain has taken its place. The fence remains.

•••

Downtown’s tangled streets contrast with the grid of right angles and straight lines imposed on most of Manhattan by a board of street commissioners in 1807. Their plan was memorialized on the Randal Map, named after John Randal Jr., the engineer and surveyor who created it and drew it by hand.

Nearly 25 years ago, Harry Kleiderman pulled me into the Manhattan Borough President’s Topographical Bureau. Harry worked there. He was tough, profane, and worldly, and I liked him a lot. His romanticism escaped only in kindness to his friends, love of history, and fidelity to the memory of Tammany Hall. The Hall had gotten him his jobs: he had been a pick-and-shovel man for the Borough Department of Works (now part of the Department of Transportation), a confidential secretary to a Municipal Court Justice, and then a clerk in the Topographical Bureau.

We gossiped about politics. Then Harry asked whether I wanted to see the Randal Map. He opened the cabinet with the reverence one might reserve for the Ark of the Covenant. The map had been made in several parts and was mounted on rollers so cracks wouldn’t form along fold lines. Harry unrolled part of it.

Randal had drawn and named the streets with India ink and watercolored the land forms. There was the Collect Pond and Minetta Brook and Kips Bay, and the rolling hills of Chelsea that would all soon vanish beneath the pavements and landfills of the city. The map was perfect and exquisite. The Topographical Bureau and its predecessors maintained it as if it were the Holy of Holies because in a worldly way, it is: it’s the root of all land use in Manhattan. I lightly touched its edge for a moment. It’s made of a heavy parchment, to endure for the ages. The Randal Map is one of the few objects I’ve touched that’s so rare and unusual as to be literally priceless. Then Harry rolled it up again and closed the drawer.

•••

For some years, I wrote for a weekly paper, New York Press, published by Russ Smith and edited by John Strausbaugh. Each man had strong political opinions; neither cared whether a writer’s politics were right or left, as long as he or she could express themselves in clear, succinct, professional prose. The paper had a namesake, the New York Press, which was a flourishing daily newspaper from 1887 to 1916, when it merged into the New York Sun. In 1890, the Press published a guide to the best of Manhattan’s illicit pleasures: Vices of a Big City.

Vices professed a high moral purpose: warning both natives and tourists against places and neighborhoods where one might find the near occasions of sin. The newspaper did this by providing an exhaustively detailed list of whorehouses, concert saloons, dance houses, and the like, organized both geographically and by specialty. The odd combination of moral rhetoric and obsessive detail, down to addresses, gives Vices the flavor of “a kind of Real Estate Board brochure apprising (out-of-towners) of the superior facilities offered by New York.”

Indeed, Vices is the kind of thing that, as Richard Rovere wrote, “exposed the lasciviousness and corruption of metropolitan life in such a manner as to make them all but irresistible,” with knowing appraisals of the entertainments to be found at Harry Hill’s Dance House, Billy McGlory’s Armory Hall, and the French Madame’s on 31st St., where “the performance is of such a nature as to horrify any but the most blasé roue.” They rated even dives like Bertrand Myers’s concert saloon at 207 Bowery, “crowded with women nightly, who smoke cigarettes and drink gin,” or the “very low” whorehouses on Water St. between James St. and Catherine Slip.

Vices also describes what was probably the city’s first openly gay bar, Frank Stephenson’s Slide, at 157 Bleecker. Unfortunately, the rhetoric is overheated, as Luc Santé notes: it was described as “the lowest and most disgusting place. The places is filled nightly with from one hundred to three hundred people, most of whom are males, but are unworthy the name of men. They are effeminate, degraded, and addicted to vices which are inhuman and unnatural.” One imagines the gay visitor who had consulted the book, ignored the rhetoric, and caught the next bus for Bleecker Street.

•••

Such guides were probably not necessary to an old friend of mine, now dead. When I spoke at his funeral, I remarked, “He will be remembered for his amiable vices long after we are forgotten for our admirable virtues.”

I suspect the Colonel simply knew by instinct where to find what he wanted. Most of us talk: he conversed, and his conversation was the sort of thing one could only find in a great city. Decorated for his services in the Second World War, his blithe good nature had survived several unsuccessful marriages and consequent financial disasters; his gifts in certain intimate matters had enhanced his standing in every sense with several mutual female acquaintances.

One evening while we were at the bar of the Regency Whist Club, he said that he disdained tap water as a beverage. This was while the City’s water was still known as the Croton cocktail, before a former Mayor compromised land use and sewer regulations around the City’s Catskill reservoirs to ingratiate himself with upstate Republican politicians and real estate developers.

I was young and perhaps disrespectful, and we’d been tossing down double vodkas as though Prohibition was returning on the next train. My inhibitions surrendered to an impulse to tell the old man this was a strange affectation. One might politely translate my remarks as to say that he had said just so much, well, stuff to me.

He arched an eyebrow, murmured, “Meanwhile,” and then reminisced about a night in Madrid when, while dining with Prince Nicholas of Romania, he had refused water.

“The Prince agreed with me,” he said, “and announced that he himself never allowed any tap water to touch his lips.” My friend continued, “I then said to him in French, the language we were speaking, ‘But, Sir, how do you manage to clean your teeth?’ The Prince immediately murmured, ‘Ah, pour me laver les dents ja’i un petit vin blanc tout special.’”