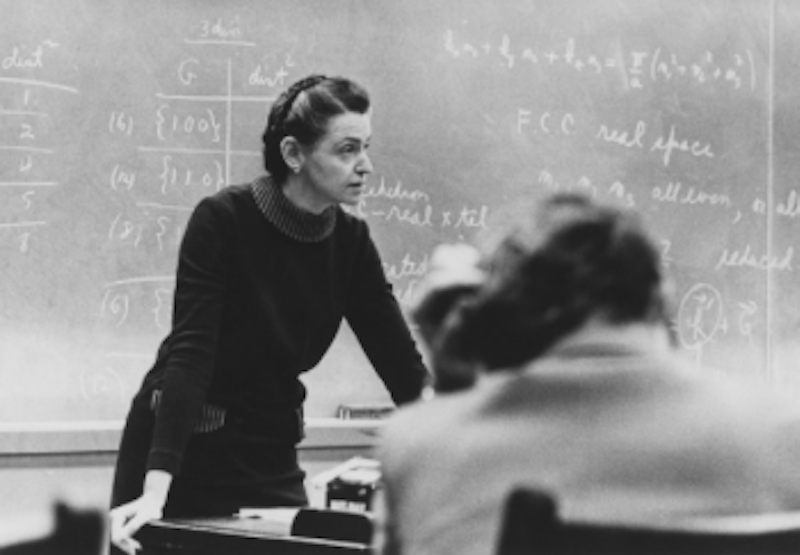

Mildred Dresselhaus (1930–2017)—physicist-engineer whose studies of carbon opened new vistas for science and technology; who published some 1700 papers; held MIT’s highest academic rank, Institute Professor; won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Medal of Science and Engineering and numerous other awards; served as president of the American Physical Society and other scientific organizations; often the first woman to achieve such distinctions—was a down-to-earth type, widely known as Millie and disinclined to seek fame.

Not long before her death, Dresselhaus starred in a General Electric commercial that asked, “What if we treated great female scientists as if they were stars?” It showed people clamoring for photos with Millie, naming babies after her, and so on. “I don’t really understand this,” she told her granddaughter upon receiving the script, but accepted it as a way to encourage young women to pursue science careers, a motivation she’d long held as a colleague and mentor. The commercial received much acclaim, with Jonah Goldberg as a rare detractor.

Carbon Queen: The Remarkable Life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus, by Maia Weinstock (MIT Press, March), is an engaging biography of a scientist who ought to be a household name, even if she didn’t seek to be one. Dresselhaus has received a well-suited biographer in Weinstock, a science writer and editor with whom I worked in 2000 at the web magazine Space.com amid the diverse leadership styles of Lou Dobbs and Sally Ride. Maia, who’s made a sideline of creating and promoting Lego figures of women in science and technology, met Millie in 2014 to present her with a Lego of the carbon pioneer.

Dresselhaus’ achievements were aided by a lack of interest in following the crowd. In the 1960s, early in her research career, solid-state physicists (who study bulk matter, rather than particles or fluids) were focused on silicon and other semiconductors, as these had clear potential in the emerging electronics revolution. Carbon seemed to offer little technological payoff, and its complex properties threatened to bog down research efforts. For Millie and her husband Gene, also a physicist, the carbon field’s sparseness was an attraction; there’d be less pressure to produce results quickly, and more flexibility to raise a family.

For the next half-century, Millie, Gene and a growing assortment of colleagues turned carbon science into an area rife with discoveries and applications. Their work would encompass the element in forms including graphene, sheets one carbon atom thick; buckminsterfullerene, a soccer-ball-like structure named for architect Buckminster Fuller; and nanotubes, minuscule cylinders that can be tweaked for desired strength, flexibility and other properties. Such research has translated into new composite materials, advances in computing and energy storage, and the emerging field of manipulating the micro-world known as nanotechnology.

Her background held little promise of such a career. Born Millie Spiewak to a Polish-Jewish immigrant family, she grew up in a rough Bronx neighborhood, but got a music scholarship to a Greenwich Village school. She attended Hunter High School, unique among the city’s magnet schools in accepting girls. Next was Hunter College, then a Fulbright Scholarship to Cambridge University and a doctoral program at the University of Chicago. Millie had classes with no other women, and professors averse to teaching one. Others encouraged her ambitions, including Rosalyn Yalow, second woman to win a medicine Nobel, and the famous physicist Enrico Fermi.

A prodigious work ethic and upbeat perseverance fueled Dresselhaus’ career trajectory. So did a supportive spouse; Gene, who had an impressive career and died last year, seemingly lacked insecurity about his wife surpassing him. Millie gave birth to four kids in the late-1950s and early-1960s, returning quickly to work each time. One vignette shows her uncharacteristically infuriated, when a lab denied her entry because her new infant lacked security credentials.

One lesson I take from Carbon Queen is that there’s nothing zero-sum about efforts to make science more inclusive of women, minorities and underrepresented groups. Economists have long decried the “lump of labor” fallacy that there’s a fixed number of jobs or opportunities; yet such an assumption seems implicit in much culture-war contentiousness. Dresselhaus’ role in opening and expanding carbon nanoscience demonstrates the benefits of getting more people to look into the innumerable questions science has yet to answer.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and is on Twitter: @kennethsilber