In Search of Smiles is a book about a drug dealer. This is Alston Frederick Hughes, universally known as Smiles, who was one of the chief distributors of LSD in the UK in the 1970s. He was eventually caught and imprisoned after a trial which began on January 12, 1978, in a case which might be one of the defining moments in modern British history. It’s also a book about memory and its fallibility, about LSD and its effects, about the British Establishment and its war on the counter-culture, about life and having fun, and about how one person, at least, strove to become the person he was meant to be.

At the heart of the book is the story of Operation Julie, the police investigation into the activities of two parallel drug rings in the mid- to late-1970s, in which 120 people were arrested, putting an end to what was, until then, the largest LSD manufacturing operation in the world. The product that came out of their labs was one of the purest, most consistent forms that illegally manufactured LSD ever took, instantly recognizable to anyone who lived through the era as the microdot, a tiny colored pill not much bigger than a pinhead that packed a powerful psychedelic punch. It was cheap (50p a pill for many years) reliable and effective and it knocked your head into the stratosphere. It altered the perspective of a whole generation of young people, this writer included.

One of the funniest aspects of the book was the discovery that Smiles had lived in Marston Green, the weird little suburb of Birmingham where I spent the last days of my youth. He was there while I was there, 1970-71—a real hippie as opposed to a teenager living at home with his parents—even while I was sampling his wares for the first time in Elmdon Park with a friend, not more than a mile or two from where he lived. If I saw him during that time I would’ve remembered.

Andy Roberts is a historian of British psychedelic culture. His previous books include Albion Dreaming, Acid Drops and Divine Rascal, which I wrote about here. He has a no-nonsense, journalistic style which concerns itself primarily with establishing the facts behind the myths while allowing his subject, Smiles, plenty of room to tell his own story. Smiles comes across as a gregarious, intelligent, brave, loyal and fun-loving individual: not at all the image of a drug dealer you might expect.

This is down to the drugs he was dealing. While he certainly enjoyed the odd cocaine bender and a few lines of speed now and then, he never dealt in these drugs. He was a proselytizer for LSD and its ability to change consciousness and, while he made plenty of money in the process, he was also very generous, spreading it around liberally among those who passed through his door or who he came into contact with during his travels. At the end of the book Roberts tries to get some of his informants to say something critical about the man, fearing that he might be accused of writing a hagiography. No one would.

Smiles’ character is perhaps best summarized by his daughter, Rachel, who says: “He’s probably the kindest person I know and he’s incredibly honest. He’s incredibly clever and when I haven’t known what to do I can rely on dad to say, ok, do this. He’s sage, he’s wise. Kind to a fault and thoughtful and really massively sensitive.”

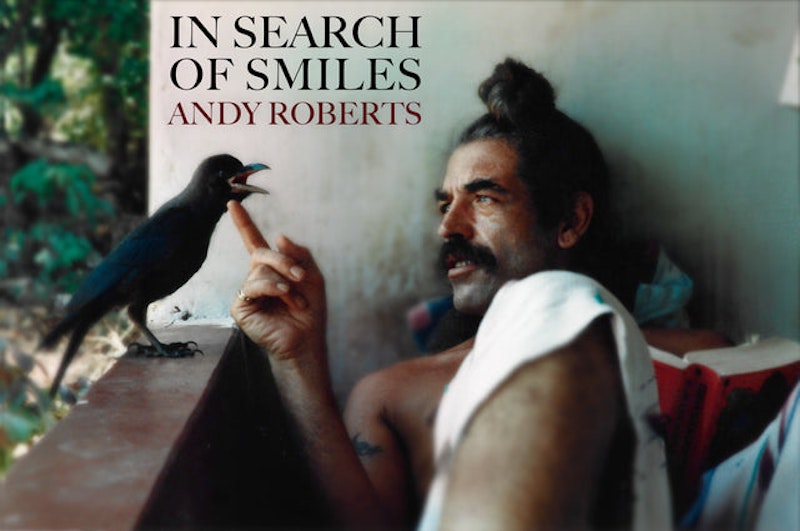

The cover of the book tells the story in itself. On the front we see Smiles, a handsome, dark-haired man with chiselled features and a moustache, long hair tied into a top knot, looking to his right. The back cover shows what he’s looking at. His arm’s outstretched and he’s chucking a bird under the beak. You can see the delight in the bird’s face, who appears to be singing, while you can also see the tenderness in Smiles’ eyes.

This stands in marked contrast to how the Operation Julie team wanted to portray him. He was arrested by armed officers who woke him up with a gun in his face. When the defendants were transported to court it was with an armed convoy with motorcycle outriders, while on the final day of the trial there were police marksmen stationed at key locations overlooking the court. British police are usually unarmed, so it would’ve taken special permission to have deployed so many guns. There was talk of connections to the IRA and the Baader-Meinhof Gang. The police would’ve known that this wasn’t true, as they’d observed the group for a long time.

Roberts makes an interesting observation. He says: “The tenacity with which the police pursued the Microdot Gang has rarely, if ever, been equalled with regard to apprehending those who manufacture and distribute more dangerous controlled drugs.” It was an immense, and expensive, operation lasting several years, including the use of undercover officers, phone taps, surveillance equipment and huge expenses claims. So why hasn’t a similar team ever been assembled to stop the work of the drug gangs behind heroin and cocaine? “Arguably because the criminals involved in the heroin and cocaine trade are genuinely violent and dangerous people and the bribes or threats offered to police officers for their collusion are substantial. Armed police hunting down peace-loving LSD chemists and distributors proved to be a much less dangerous occupation.”

Two undercover officers were assigned to watch Smiles in the tiny village of Llanddewi Brefi in West Wales. These were Stephen Bentley and Eric Wright: known in the village by their false names, Steve Jackson and Eric Walker. Bentley later went on to write a book about his experience, Undercover: Operation Julie—The Inside Story. This is one of the most interesting aspects of the book as it allows Roberts to contrast Bentley’s memories of the events with those of Smiles. There are numerous contradictions in the accounts, the main one that Smiles says he knew they were undercover officers and told them so, while Bentley seems to think that their cover held relatively well. This is despite the fact that no information obtained by the officers was used in the court case.

The other fascinating aspect of this is the effect that being undercover had on Bentley. He grew to like and admire Smiles during the course of the operation and, in the guise of a hippie, he was required to take drugs with his quarry. They spent many evenings together stoned on Smiles’ high-grade hash and became friends. As Roberts puts it: “The tension between maintaining the false persona of ‘Steve Jackson’ and his real identity of Steve Bentley was reaching unbearable levels and at one stage almost led him to drop his cover story and confess everything to Smiles in order to warn him of the danger he was in.”

Smiles’ motives for the trade he chose to pursue are made clear in the book:

I have to say, acid changed my life—it was a real force for good for me and we thought we were doing something good for the world. I wanted everybody to understand that everything is absolutely and inextricably connected. I wanted people to understand that everything we do has an impact, so that if we change what we do, we can make the world a better place.

Did he make money from it? Yes he did, and this was the main thrust in the prosecution case against him and the other members of the gang. There was lots of money sloshing about. It was a sellers’ market. Everyone wanted what they had to offer. But their markup was minuscule, the philosophy being “sell it as cheap as you can, man.” The only reason they made so much money was because they were shifting it in such large quantities. Meanwhile Smiles was a one-man industry in Llanddewi Brefi, bringing wealth into the economy and good cheer into the pub, where he was often seen buying rounds.

As I say, the case against them was built entirely around the money they made as the prosecution was unable to show any major harmful effects. The one expert witness, Dr Martin Mitcheson, said that LSD was less dangerous to health than heroin, cocaine, amphetamines and barbiturates and shouldn’t be a Class A drug. A study of death certificates had not found a single one giving LSD as the cause of death, he said. His testimony was ignored.

The irony of this is where the court case took place. This was in Bristol Crown Court at the city’s Guildhall. As Roberts puts it:

In the 17th and 18th century, the City of Bristol had been a key port in a cycle of extremely profitable but morally dubious maritime trade. Arms and alcohol were sent from Bristol to West Africa and traded for slaves who were then ferried across the Atlantic in appalling conditions to be sold in America. Tobacco, molasses and slaves were then shipped back for sale in Bristol, a trading cycle that established the economic success and civic reputation of the City on barbaric practices and commodities that caused misery and death to thousands of people.

The Guildhall court room stood on the site of the slave auctions. The auction block on which the slaves were sold was where the dock now stood. There were oil paintings on the walls celebrating the history. As Smiles described it, “There was all these pictures of people being sold on the block, bales of tobacco, all that shit, what the fuck you telling me?”

What they were telling him was that they really didn’t care about people making money or harming other people with drugs. What they cared about was that it should be the Establishment doing these things. There was also an ideological question. Smiles and his friends weren’t really punished for selling drugs. They were being punished for stepping outside the cultural norm, for deprogramming a generation, for creating a new culture, one that was opposed to the dominant world view of the Establishment, which was even then in the process of destroying the world. They were revolutionaries, but not with guns, with consciousness. It was “a revolution in the head.” As Roberts says:

The trial perfectly illustrated the British Establishment, that thousand-year-old interlocking web of legislated power, privilege, status and wealth, as unable to countenance anyone who wished to expand their consciousness via the agency of LSD.

Smiles was unrepentant as he stood in the dock to receive his sentence. He expressed no regrets and offered no defense. His barrister made one, brief, pointed statement: “If the shareholders of the distillers can sleep easy in their beds well so will my client.” He was given an eight-year prison term, which he served with alacrity and wit, after which he returned to his outlaw life of adventure.

—Follow Chris Stone on Twitter: @ChrisJamesStone