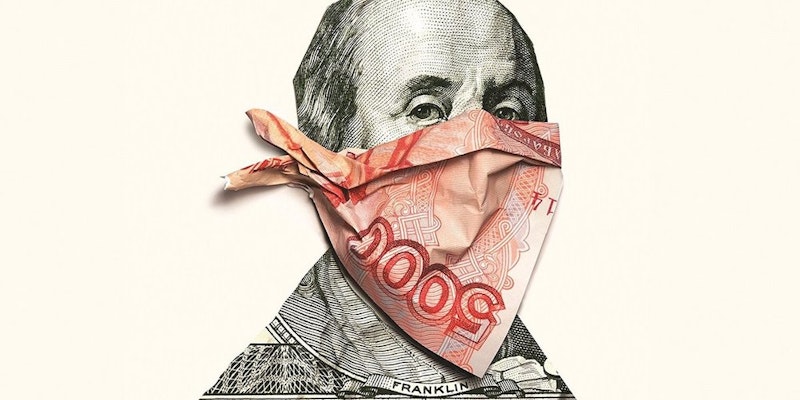

Oliver Bullough’s Moneyland is a geographical study of a nation that has no geography; no borders, either, and no territory as it’s usually understood. This is a conceptual land, shaped not just by money but dark money. Its flora and fauna are a hodgepodge of species from around the world making a bizarre ecosystem: Swiss bank accounts, passports from Malta, diplomatic credentials from the Central African Republic. Bullough attempts to map out the contours of this hidden continent of wealth, and explain what its quiet imperialism means for the rest of the world.

Moneyland’s surprisingly engaging for an economics text, dominated by Bullough’s wry voice as he lays out in simple terms how the global dark money supply grew and why—along with what it’s being used for now, and why it’s a problem. Bullough has a knack for breaking down complex financial concepts into simple explanations, vital for what he’s doing. This is a determinedly popular natural history of the non-country of Moneyland, aimed at making clear what’s happening in the land of the ultra-wealthy.

The first chapter gives a brief overview of the early days of Moneyland, starting in the 1960s with the invention of bearer bonds, which, paired with Swiss bank accounts, allowed for money to become not just hidden but mobile. Bankers excused the existence of these instruments as a way for Jews who’d stuck money in Switzerland before the Second World War to move it easily to wherever they’d gone on to build a new life. Unfortunately, it also made it easier for fleeing Nazis to build their own new lives as well.

Things have become much more complex and flexible since those days, and much grander in scope. Thus the buying of passports and indeed of ceremonial diplomatic positions that confer diplomatic immunity. Bullough spends a fair amount of time trying to get across how big a problem Moneyland is, not easy when dealing with numbers in the trillions. He also tries to get across the nature of the problem Moneyland poses, and here he’s got a less difficult job.

The basic problem with Moneyland is corruption. There’s some dark money that’s dark for potentially good reasons, but not much of it. Some of it’s dark for sleazy reasons—to hide assets from a divorce court or a bankruptcy court, say. And some of it’s dark because it’s been gained illegally, or extracted improperly by a leader from his or her country, usually a country that can’t afford the loss. Bullough identifies a set of processes that allow the money to be hidden, laundered, and spent.

He also, crucially, shows the end result of Moneyland’s influence by recounting scenes from the Ukraine. In his telling, Ukraine’s a society almost entirely corrupt—that is, in order to live and keep the machinery of life going, you need to take part in corruption. Hospital technicians have to take bribes from patients not just to keep a roof over their heads but to keep their machines going. The money that’s supposed to take care of those machines and hospitals has been stolen; it has been drawn into Moneyland.

If the worst of Moneyland’s effects are local, Moneyland itself is global. Partly because it draws inhabitants from around the world, businessmen and oligarchs and royals of various countries. But mainly because it operates by pitting countries against each other, by selecting the best jurisdiction for its needs—finding the nation that requires the least information when incorporating a business, say, so you don’t have to state who’s behind it. Or choosing which country has the most beneficial tax shelter. Or simply finding a way to slip between the laws of two different countries. It’s the downside of globalization, a race to the bottom in global finance.

The rich don’t do all this on their own, of course. Whole industries that grow up around them, dedicated to helping them, dedicated to trying to get a piece of their pie. Bankers and financial services. Lawyers, naturally. But concierges, as well, people who know how to find things and get things done. Real estate dealers. And PR men, who shape the narratives of Moneyland—along with libel lawyers, who establish what cannot be said. Moneyland’s global ability to select the most convenient legal code from among a host of nations comes into play here as well: libel tourism lets a rich person who wants to stop news from spreading select a jurisdiction (the UK is popular) in which to bring a suit that could potentially ruin an inconvenient truth-teller. Even if the truth-teller wins the case.

Accordingly, one wonders what Bullough himself cannot say. He gives an extended example of a story he couldn’t run, because outlets contemplating it received threatening letters from lawyers determined to quash it. The bullying worked; his recounting of the episode in the book has to be so general the principals can’t be identified.

That case notwithstanding, he presents some remarkable interviews, particularly with weary Ukrainians describing failed efforts to stop corruption in their country. He describes various run-arounds he’s given by agents of various bureaucracies. He also cites a number of authorities in endnotes, but the main flow of the book isn’t bogged down by precise attribution—again, this is a book aimed at the popular market.

And as such it works. The structure’s very loose, but Bullough’s repetition of his central points is effective at driving them home. Moneyland, he argues, is a global structure always seeking the weakest points in the international system that’s supposed to regulate finance and keep things above-board. The love of money, it has been observed, is the root of all evil; Bullough shows how the one produces the other, at enough of a distance that the rich people who indulge their love don’t have to face the evil. They can pay other people for that.

Remarkably, this isn’t a despairing book. It has a tone of gentle irony that mostly works. Bemusement may be the best word for his approach: bemusement at how a system built by bright people with the best of intentions produced not just occasional corruption but a shadow-country, a weird anti-geography whose community is built on corruption.