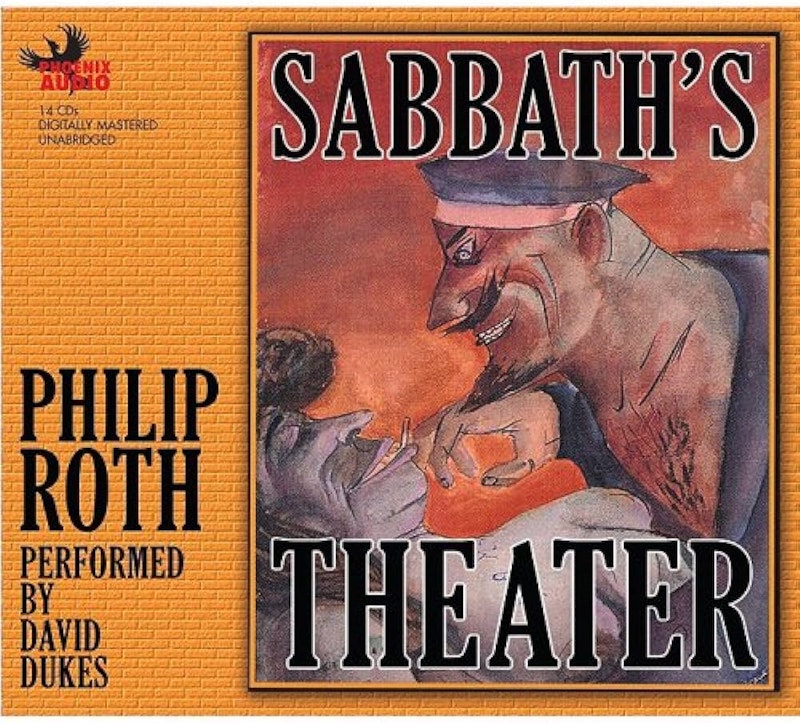

When I first read Philip Roth’s transgressive novel Sabbath’s Theater, published in 1995, I wasn’t ready for the author’s profound insights on life. At 44, I placed it back on the shelf having labored through the final pages in which protagonist Mickey Sabbath takes stock of his life. Recently, I re-read it, drawn by a memory that those pages might contain guiding principles and wisdom. Almost 30 years older, I was ready for Roth’s harrowing and eroticized treatise on marriage, aging, and mortality.

Mickey Sabbath is the flawed husband whose relationships with the women he obsesses over range from abusive to degenerate. A totem of phallic instinct, he’s forced to leave New York City after his exploits as a hand puppeteer and theater arts instructor, which include the recording of a lusty audiotape between him and a much younger female student, land him before a local magistrate, who hears testimony from accusatory women in the full blossom of feminist activism.

He relocates to the fictional Madamaska Falls, a small village upstate where he lives with his acholic second wife, and cheats on her with a local innkeeper’s wife, Drenka, a Slavic near-beauty who narrates to Sabbath the particulars of her string of extramarital affairs even as the couple has sex. Reading the novel in my mid-40s, I was captivated by Roth’s creative delve into the sexual behavior of uninhibited lovers—both Sabbath’s wives at the beginning of their relationships, and his “other” women. But the protag’s suicidal ideation and existential gnashing of teeth became tiresome as the story wore on.

Now in my early-70s, I found trenchant understanding on virtually every page of the book. In this excerpt, Sabbath reflects after Drenka succumbs to ovarian cancer and he learns that she’s left a diary revealing all, found by her surviving son, a Madamaska Falls police officer: “Or had she left it behind because she had not the strength to throw it out? Yes, such diaries have a privileged place among one’s skeletons; one cannot easily free oneself of words themselves finally freed from their daily duty to justify and conceal. It takes more courage than one might imagine to destroy the secret diaries, the letters, and the Polaroids, the videotapes, the audiotapes, the locks of pubic hair, the unlaundered items of intimate apparel, to obliterate forever the reliclike force of these things that, almost alone of our possessions, decisively answer the question: ‘Can it really be that I am like this?’”

As the story winds down, Sabbath is invited by a former associate to attend the New York City funeral of their former creative partner, whose ostensibly happily married life has ended in his suicide. Afterwards, Sabbath visits the shoddily-tended urban graveyard where his parents and brother—shot down in a B-52 bomber over Leyte in WWII at age 20—are buried. He purchases a plot for himself. Finding nothing but dreary memories and dissolution in NYC, he escapes again to Madamaska Falls, and on the dark night of his return throws himself weeping on Drenka’s grave. She, for him, represents the resonate love of a lifetime, and a reason to go on living.