There’re a handful of scenes I have to write. But they’re big scenes. Some have a lot of characters and events, some have heavy emotion. Each of them completes the story of one character or another. As I see it, each scene tells you (sorry, shows you) why we’ve been following the character. The character’s life comes out in a certain place; the character ends up, and we see what they’ve been doing in the book all this time. When these scenes are done, my book is done. No, I can’t write them and you can see why.

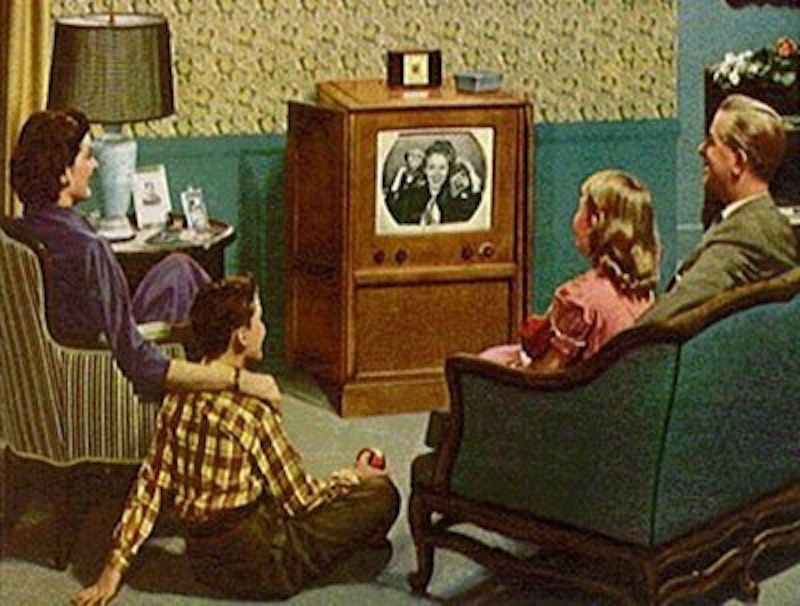

An added problem: some of the scenes I believe in, well, not so much. I know how their plot lines came about. The main action of the novel runs from 1965 through 1969, the years that my book’s made-up TV series is on the air. I know that I looked at my timeline and saw that, for two of the characters, the second half was largely bare. These were the two older members of the TV program’s cast. One is an amiable but selfish ex-cowboy actor, the other a gallantly professional B-movie actress. They’re both pushing 60. I’d written some good scenes for Harry and Tony, but in each case this meant one big scene and a few smaller ones, and each of the big scenes left its character with years to go before the action hit 1969 and the finish. I tried to think honestly about what unfinished business I could fill in for the two. I came up with material, and I know it’s the result of conscientious effort to cope with an artificial problem. This doesn’t inspire confidence.

But I do believe in the scenes about Olsen and CG, the show’s junior leads. Their story is one I feel like telling. But not enough to actually tell it. I believe in their story, but I know the work involved in writing about emotion. If the stuff doesn’t surge out, it must be picked free of the interference cluttering its face. Dust is sifted out of the way, and an edge becomes visible here, a corner there. The pouring-out process can be more convulsive than I like. The picking-and-sifting process is worse. It takes cross-eyed attention to the back of the mind, and it keeps going for as long as I don’t feel sure, which is forever except I stop. At the time it feels like a life sentence.

With other characters, problems hit me from other angles. I have a black character, Washington Ferris. Over the course of years, I hit on a series of events for him that I liked. One came to mind, and then another down the line, and then another in between those two. I saw where I’d been going, and I wound up with an outcome that chuffed me because it suited him so well (he’s a nut). Then social media put a thought in my mind: this outcome depended on having a black man driving around 1960s Los Angeles. In fact, he had to do it regularly and at length, as a pastime, and he’d be driving a fancy car. What about the police? Now, conscientiously, I have to answer that question, and I hope the plot line is still intact when I’m done.

We’re left with two more characters, the main protagonists of the book. This is Eppinger, the foolish old man who started the TV show, and Len, the canny but emotionally dislocated young fellow who pushes him out and takes over. Eppinger suffers from the same problem as the other old characters: not enough to do in the book’s later parts. He sits around and gradually senses that Len has frozen him out. Actually, I’ve written those scenes, but they’re short on forward motion. What must be written is Eppinger’s discovery that his TV show, though canceled, has held on to its fans. They still love him, they’re crazy about him, and the vain old fellow feels the sky smile at last. Doing this scene shouldn’t be so hard. Eppinger gets an invitation in the mail to be guest of honor at the first fan convention for his show. The twist: Eppinger, being a dummy, had met one of the organizers and told him all the reasons a convention made no sense. Now here he is, being disproved, and he’s forgotten the conversation (he was tanked). Nor does he sense how big a windfall lies ahead. But he opens his mail and history finds him.

I suppose what bothers me is that he’s alone. A bit of aloneness goes a long way, and my novel has a lot. Eppinger already gets the largest helping; yet here, at his climax in the story, he’s alone again. It bothers me how I rioted in Eppinger’s aloneness when thinking up his denouement. Before his moment with the envelope and the invitation, I planned for him to trek home along the winding streets and tiny backyards of the Hollywood Hills. He’d do this on foot, drunk from a party and taking disastrous shortcuts, and it would be at night. Given the period’s Manson atmosphere, I’d better think some about why he doesn’t get shot—in fact, might readers expect him to get shot? And why did I want to do one more long scene in which Eppinger is all by himself? I suspect that I fell into a creative slouch, that I did what came easiest and then felt as if inspiration had burst forth. And it’s been 14 or 15 years since I thought of Eppinger’s trek. All that time I figured I at least knew what his ending would be, even if the others threw me. Now I decide otherwise.

And don’t ask me about the young guy. Back when I thought up Eppinger’s trek, I was making my first attempts at Len’s scene with his parents. It’s been a decade and a half of emotional paralysis, and that deserves a post in its own right.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3