Many people—enough, at least, to create a recurring Internet incantation—are convinced that the “return to normal” will be stymied and crippled by all of their new mental disorders and illnesses. I’ve lost my head—check to make sure? I’m not sure how one could lose the ability to function socially in a year, unless alone in a cave or solitary confinement. The modern world is lonely and everywhere there are walking marks, whether for money or ideology. I don’t think anyone would dispute that—despite having a Democratic president and a media and pop culture that are, especially lately, aggressively permissive and high on acceptance—we’re living in a conservative period. When people are afraid to speak what they feel, they’re living in a conservative period.

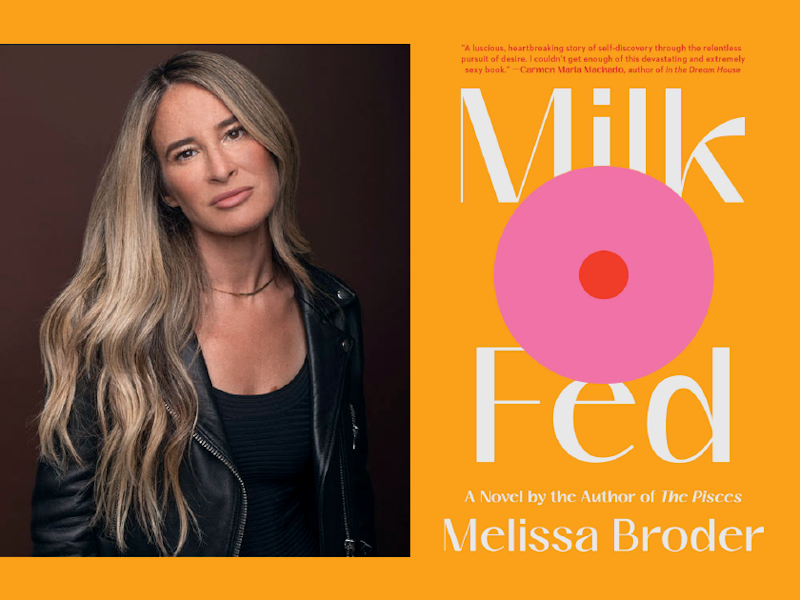

Melissa Broder occupies a safe place in contemporary literature, but she distinguishes herself by evoking a vast modern loneliness and the extreme specifics of the most personal and graphic fantasies and desires a person can have. Her work is often revelatory, and with her new novel Milk Fed she accomplishes something very difficult: make the traditionally “disgusting” into something beautiful, even erotic. She’s a writer who’s more unbridled than she gets credit for.

Milk Fed follows Rachel, a young woman in her late-20s working at a talent agency in Los Angeles. She’s single and has an admittedly severe eating disorder, exacerbated by a simultaneously overbearing and emotionally cold and distant mother. “A bad Jew,” still one who falls in love with an Orthodox woman at the frozen yogurt place she goes to for a precise calorie count. The Orthodox woman, Miriam, weighs a lot more than Miriam and doesn’t seem to care about it at all, much less the opinions of others. After fantasizing about being mothered and seduced by her female boss, Rachel dives into a slow burn affair with the observant Miriam, who plays and remains hard to get until she can hold no more.

Moments in Milk Fed are riskier than any adjacent fiction, and the novel’s focus on bodies and (interior) spaces is surely du jour, but much of it would likely disgust the typical reader of wandering romantics and White Fragility. Broder’s prose, as in her essays, veers from the vernacular of Twitter to moments of cutting insight (“It seemed that as long as I wasn’t actually having sex with a person, I could get off to them. But once they embraced me it was over.”).

Rachel is a familiar type, rendered most vividly (or widely) by Lena Dunham in Girls and Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen’s Portlandia, but her inner voice is much closer to the titular Eileen of Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2015 novel. Her descriptions of food go on and on, and they’re in fair proportion to the sections that describe the bodily process and how it handles fasting, binging, purging, and even eating normally. Broder goes where others fear to tread: in food, sex, love, and desire.

After a clandestine stay at Miriam’s family’s house, Rachel experiences the comfort and security of a real family and tradition for the first time: “Miriam had traveled fewer places than I had. She still lived with her family and had no grand plans for any kind of career. Yet somehow, she seemed to be moving forward more freely than I was, or if not forward, then deeper and higher, in a series of infinite crescendos. While I was aggressively pedaling nowhere, she was orbiting peacefully.”

Earlier, she admits she knows their love is conditional, “dependent on my being Jewish.” Later, she foolishly questions the mission of the IDF and the ethics of displacing Palestinians from their land—at a Sabbath dinner with the whole Orthodox family, including a young man around the same age just back from his first tour with the IDF. He gets up silently and goes to the bathroom, but the mother lays into Rachel, accurately assuming she has no idea what she’s talking about. The mother asks why the rest of the Arab world “had to get their piece in,” and that, “it’s all anti-Semitism.” Why didn’t they give them a slice of Egypt? She asks. Rachel doesn’t know, can’t respond, and is then politely but forcefully asked to leave. Her relationship with Miriam, save for one last fuck, is over.

On a similar note of intimacy, I re-watched Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny recently, and again what stuck with me wasn’t the climactic blowjob (magnificent as it is—no, I don’t think it’s a dildo), but a scene earlier on when Gallo’s character stops at a gas station. There’s a burger place and some metal tables nearby. He gets some food and sits down outside, and behind him is a crying woman, blonde and worse for wear. In a wordless exchange and communion, he goes over to her, they hesitantly embrace, and eventually kiss passionately as she continues to cry. He gets up and rides off on his motorcycle without saying a word. A moment of love, or something close to it, in the ultimate territory of modern loneliness: the highway rest stop.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith