I’ve never participated in any sort of “book club,” which unfairly or not, always summoned an image of suburban coffee or white wine gatherings of (mostly) women who, after a cursory examination of a best-seller, devolved into chatter about family, school and catty neighborhood gossip. As I recall, my mom tried out this activity at some point in the mid-1960s, dutifully reading some interminable James Michener novel, making notes, and sipping Sanka along with six or so other women. She was an avid reader—some trash, some quality books—but sooner rather than later became bored with the exercise.

However, over the past five or six years, I’ve traded book recommendation emails—and before this year, semi-annual in-person visits—with my longtime friend Gary Frahm, who was a top advertising salesman at Baltimore’s City Paper in the mid-1980s. Just last week, Gary emailed about a Splice Today article, and I responded that I just finished Fredrik Backman’s fine new novel Anxious People (Backman’s Swedish, so his books are released in translation a year later). Gary emailed back a virtual smile, said he’d just finished it too, and tipped me off to Backman’s Beartown—easily the best sports (hockey)/cultural novel since one-hit wonder Chad Harbaugh’s 2011 The Art of Fielding (baseball)—and I said that was old news, buddy, but have you read Beartown’s sequel Us Against You?

It’s good-natured banter, and I’ll return to the man my City Paper co-proprietor Alan Hirsch and I referred to as the “Frahm Monster” or “A Fellow Named Frahm” in due course. But first, a few sentences about Anxious People, my favorite novel this year, along with Ottessa Moshfegh’s Death in Her Hands. Backman’s not yet 40 but unlike many of his serious contemporaries in the dwindling literary circle, he’s prolific: since his stunning 2012 debut A Man Called Ove, a book that hit the trifecta: quality writing, best-seller and adapted into a critically acclaimed film. He’s written several other books, and the only dog among them, at least in my estimation, was Britt-Marie Was Here (a slog—Backman doesn’t often write short—despite lots of typically trenchant observations, a complicated lead character and one-liners). In any case, Anxious People is a departure—one of Backman’s strengths is his breadth of narrative arcs, unlike another favorite writer of mine, Britain’s Jonathan Coe, whose books are usually in the same ballpark—from the twin hockey novels, OCD-addled Ove and cranky but lovable Britt-Marie. It’s a fantasy, or more accurately, a fairytale, about a phantom bank robbery from a cashless bank in a small Swedish town, in which a dozen or so characters play major roles. Though light-hearted in one sense, Backman also completely eviscerates the banking industry, especially lending agents who encourage people to spend beyond their means, and then, when a recession hits and homeowners are out on their asses, the banker shrugs and says, “You didn’t read the fine print,” and moves along to pushing more paper and raking in the dough.

Backman devotees will choose varying favorite characters in Anxious People, and I go with the father-son cop duo of Jim and Jack who are in charge of the robbery investigation—and go about solving the mystery in ways that are generational, the older on gut feeling, the younger on cold facts aided by his computer skills—and ostensibly get on each other’s nerves. (Although both are in agreement that the bureaucrats from Stockholm are busybodies to avoid if possible.) Never far from their thoughts is their late wife/mother, a freewheeling priest who lived with gusto, enjoying herself while traveling the world helping poor people, and not incidentally, running afoul of the church.

Not long before she died, the priest was stabbed in a riot far away, and while Jim was just relieved she was okay, Jack, stifling his tears, yelled at her for reckless risk-taking. The narrator: “His mom realized, of course, that her son was shouting out of fear and concern, so she replied the way she often did: ‘Boats that stay in the harbor are safe, but that’s not what boats were built for.’”

As Anxious People moves a brisk pace, what the reader initially thought of indifference or hostility on Jack’s part about Jim, turns into something more complex. Jim isn’t really a bumbler, Jack’s not really a bitter young man, but rather both, cemented by memories of the wife/mother, are each other’s foundation. That reality isn’t directly acknowledged by either of them, save quick sentimental moments when at night sharing some whiskey, but they’re the sorts of people I’d like for neighbors, anxious or not.

As noted above, Gary and I agree on Backman, as well as Sam Lipsyte (save his recent turkey Hark), Richard Russo, Coe, Jonathan Dee, Anna Burns, Donna Tartt, Nathan Hill and Sally Rooney. We quibble about Michael Chabon, Gary Shteyngart and Chip Cheek. I can’t remember if we’ve traded comments about Per Petterson, one of my favorites, or Roddy Doyle, but really that’s neither here nor there.

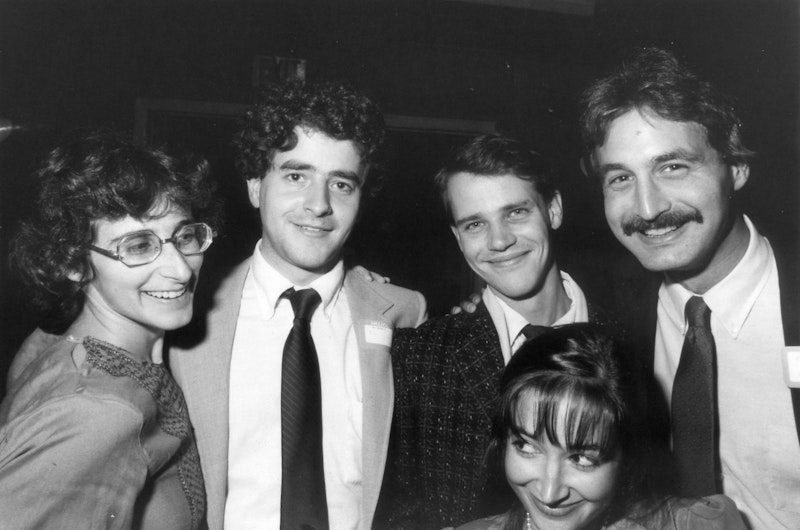

I didn’t read much fiction in the 1980s when Gary and I worked together—all periodicals and non-fiction—and I’ve no idea if he did. City Paper began publishing in 1977, and Alan Hirsch hired Gary away from Baltimore magazine—a fat, ad-rich monthly—at the start of 1983, just as CP was emerging from very lean—meaning debt—years. He was our first “star” hire, a professional who courted upscale advertisers and helped the paper reach a new level. That’s called profitability. His enthusiasm was gratifying—except when he’d call me at 11 p.m. to talk business as I was winding down with an I Love Lucy re-run—and contagious among the junior sales staff. Naturally, he tried to influence the paper’s writers to plump a client (editors Phyllis Orrick and Michael Yockel, both of whom grew fond of Gary, could tell stories about those early encounters), but after receiving a few frosty rebuffs, he adhered to the Chinese Wall separation between departments.

Memories are random, and Gary probably doesn’t recall this particular moment, but he took me aside one day in ’84, in the sales office, and said he had a small gift for me. It was the mini-Bic lighter, a white number (he no longer smokes) and I was delighted. So compact! So easy to carry in a pocket! That we both fell for this gimmick—after all, the new lighters ran out of fluid faster than the standard models—didn’t matter. We lit up—needless to say, inside smoking bans were still many years away—and toasted our friendship.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955