Robert Heinlein wrote “Every man wants to kill a bad man and love a good woman.” I think, allowing for a certain fluidity in the definition of what constitutes a bad man or a good woman, that he was essentially correct. For what he’s saying is simply every man wants to feel justified in his existence. Which means every man wants to occupy the space he feels he was meant to occupy.

I’ve always been struck by the David Bowie song “Star”: What Bowie’s saying is that unless he occupies a certain role and space, then he can’t sleep, he can’t love, he can’t really exist to his own satisfaction. Bowie’s comprehension of this inner need is a smart piece of self-analysis.

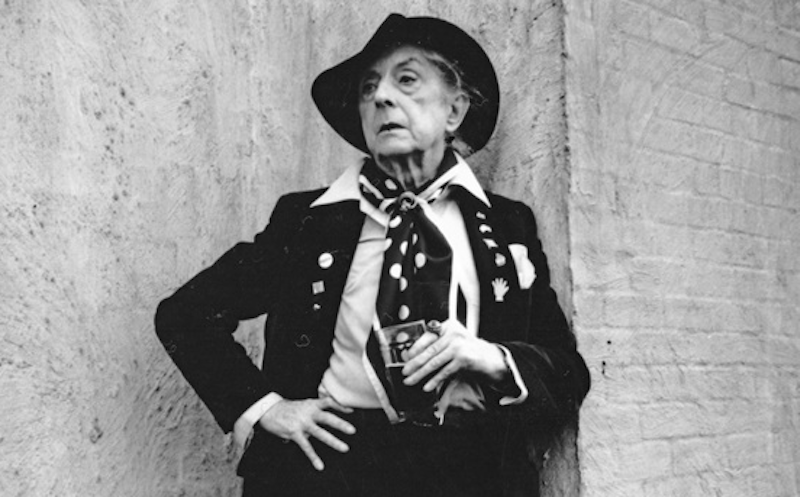

There’s a fascinating documentary made in the late-1960s about the writer Quentin Crisp. He hadn’t been able to exist as he felt he must. What we see in this documentary is a man for whom life is the unwavering pursuit of the conditions necessary to be alive. His stoicism borders on the heroic, he allows no compromise. We see how desperately he needs celebrity. He had groomed himself perfectly for the role in manner, dress and speech, yet at the time of the filming, there had been no takers. This changed with the publication of his book The Naked Civil Servant and his rise to talk-show guest status. For Crisp the “bad man to kill” was bourgeois normality, the “good woman to love” was the lifestyle he adopted, that of a socially acceptable “effeminate homosexual” as he refers to himself in the film.

In an interview, John Waters said, when asked what he would’ve done if he hadn’t become famous, “I would’ve killed myself.” This suggests that his existence would only meet his satisfaction when he was occupying a very particular role. Unlike Quentin Crisp, he was allowed to play his chosen role at a relatively young age.

The desire for one’s proper place can take on outlandish proportions. Consider The Golden House built by the Emperor Nero. It was in the middle of Rome, “on more than 200 acres of land… [The] whole area was laid out as a park with porticoes, pavilions, baths, and fountains, and in the center an artificial lake was made, on the slopes of the Velia at the east end of the Forum, a grandiose colonnaded approach and vestibule were constructed, within which stood a colossal gilded bronze statue of Nero (himself).” When The Golden House was near its completion, Nero remarked, “At last I can live like a human being.” I think for Nero the “bad man” was the presence of any limiting factor to his desires. The “good woman”? Perhaps absolute power.

Occupying “the right place” doesn’t have to be grandiose. Perhaps it’s more satisfying when it’s simple. When I was a child I recall seeing, in the local supermarket in Baltimore, a group of older men working behind the butcher counter. At that time they would’ve been around 50. As you’d expect, they all wore white, somewhat bloodied aprons but in addition, they also wore blue baseball caps with the names of various Navy ships on them. I thought they seemed immensely satisfied, happy and content. They had every right to be satisfied, as veterans of WWII they’d participated in saving the world. They had killed their share of “bad men.” I imagine. And maybe the “good woman” was life itself.

The desire to occupy one’s proper role has led to the explosion of sexual identities in recent years, from LGBTQIA+ to sex change operations. In this case, determining what constitutes the “bad man” and the “good woman” becomes complex.

Perhaps the strangest of all these “roles” is the Consistent Failure. I’ve met people who seem to unerringly make what are considered “the wrong choices.” These people complain, criticize, deride unfairness of existence but strangely enough seem satisfied in their dissatisfaction. Perhaps their “failure” is a sort of proof that the world itself is the ”bad man” and not succeeding in it is equivalent to loving the “good woman. More tragic, imagine a life where one feels a constant dissatisfaction but is unable to identify the role they need to occupy. It’s terrifying to contemplate.