In Being and Nothingness Jean-Paul Sartre describes a phenomenon called “bad faith,” a condition in which a person burlesques a role that he or she feels is socially necessary, but which no one takes entirely seriously, the actor included. He gives a few memorable (and amusingly ur-French) examples—a waiter who bustles around so briskly, so efficiently, the tips of his moustache twitching, a towel over his arm, “monsieur” and “madame” trilling from his lips like the call of a bird; or a young couple out on a date, toying with their food, neither one admitting that the whole exercise is about sex. In both cases people are playing—the waiter “is playing at being a waiter in a café,” and the young woman on the date is playing at being involved in a courtship that is not about bodies.

In Sartre’s conception bad faith is a non-threatening way of giving other people what they want while (possibly) reserving a more transcendental consciousness for the self. “A grocer who dreams is offensive to the buyer, because such a grocer is not wholly a grocer,” he writes. The grocer, or the waiter, may in fact dream, and he may know things about being a grocer or a waiter that most people would find aesthetically or morally unpleasant, but behind the happy façade of bad faith his dreams do not disturb his customers. The woman in the café blandly repositions the date as a romantic meeting of personalities rather than a prelude to sex, but she doesn’t exclude the possibility, Sartre describes how when the man takes the woman’s hand she doesn’t withdraw it but neither does she clasp him in response; she remains indecisive, conscious of both possible interpretations of the situation (she wants to sleep with him, she wants to read poetry to him near a pond) without favoring either.

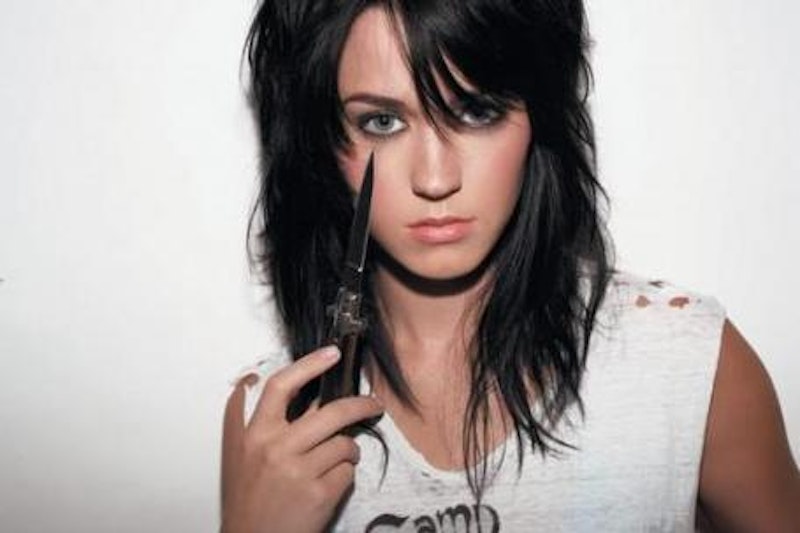

I couldn’t help but think of this café coquette as I listened, several times, to Katy Perry’s wildly popular debut album One of the Boys. About a year ago I saw Perry’s inarguably amusing video for “Ur so gay” and I have been meaning to buy the album ever since. No rational person could argue that Perry has a lovely voice, or that her compositions are particularly good, or that her lyrics possess the political and lyrical éclat of Dylan. Yet Perry’s music does not lack for pathos or rough loveliness, and her lyrics perform an almost unfathomably convoluted dance between loud and tacit meanings and, in their own seemingly trashy, over-packaged way, paint a gritty portrait of post-postmodern femininity circa 2009.

The album’s titular first song, the delightfully cringe-inducing “One of the Boys,” casts Perry as a freshly pubescent teenager: “Over the summer something changed / I started reading seventeen and sha-ving-my-legs / And I studied Lolita religiously / And I walked right into school and caught you staring at me.” Perry initially celebrates her boyish traits, like being able to burp the alphabet upon a “double-dog dare,” a line that she sings with a surprising throaty pathos, as if bidding it goodbye. Later she discards them, wishing to smell like “roses, not a baseball team”—throughout the album Perry pays unusually close attention to smell and taste.

The song seems simple: Perry has grown up and wishes to shed her masculine (or at least boyish) affectations in favor of her natural femininity. But on close listening it’s clear that Perry realizes that this femininity is just as affected and unnatural as her tomboy romping. The seemingly clumsy meta-textual wink at Lolita makes it clear: Perry’s character is burlesquing being a girl as much as she ever burlesqued being a boy.

And this use of gender characterizes the rest of the album, particularly “Ur so gay,” which brims with cheerful viciousness; it is a delightful song and something of a departure from the usual positive pop fare with which Perry competes. In it Perry heaps abuse on an ambiguously gendered boy with whom she has fallen in love: “I hope you hang yourself with your H&M scarf / While jacking off listening to Mozart,” she begins (in deference to Perry’s under-18 audience my album replaces “jacking off” with a record-scratch sound). Clearly “gay” is the album’s best-written and most-amusing song, full of trenchant and witty details. Yet in its slowest and most lyrical moment Perry sings “I wish that you would just be / real with me.”

The sentiment is so conventional and so irreparably wedded to contemporary pop music that it passes almost unnoticed, yet in Perry’s oeuvre we find an artist who concerns herself with how exactly a person might be unreal before she asks for him to be real. “You’re so indie rock it’s almost an art,” she sings earlier in the song, and again we return to the artifice of bad faith. Her ambiguous interlocutor is performing his mixed sexuality, his angst and his bohemian intellectualism, and he performs them in bad faith. Perry may or may not have the ontological authority to determine that beneath the boy’s pale and manicured exterior (“You need SPF 45 / just to stay alive!”) lies a struggling subjectivity; yet in a person who seems to be wholly one thing she surely detects the hoof prints of false consciousness. A grocer who dreams is insulting because he is not wholly a grocer, and an indie-rock waif who abandons his dégagé disdain admits a similar imperfection.

The music video cleverly dramatizes the tension through wan, unhappy-looking dolls representing Perry and the song’s apostrophic target. Towards the end of the song the boy-doll gets drunk and Perry’s avatar removes his pants (“You pull ‘em down / and there’s really nothing there”) revealing his featureless plastic crotch. She flings up her jointless doll-hands in exasperation. Similarly, in “Mannequin” she wishes that her lover came with a remote control so that she could get him to talk, “even pull a string / for you to say anything.” “I wish you could feel,” she continues, “that my love is real / but you’re not a man.”

It may seem, at this point, as if Perry’s lyrics accept the binary opposition of real and unreal, but recall Perry’s mannered, liminal toying with the idea of the nymphet in “One of the Boys.” The video, also, calls realness itself into question—after all, the Katy Perry doll gives no indication of having working genitals, and when Perry herself appears in the video she smirks cheerfully against a background of cartoon clouds, reclining with a mint green guitar in some halcyon 1950s rockabilly meadow that surely never existed, nor will it ever exist.

The sociologist Erving Goffman’s classic Presentation of Self in Everyday Life argued in part that we wear masks of behavior designed to please those around us; he also argued that there is no backstage to this performance, that beneath our masks are other masks, not a face. Sartre put it more cryptically when he wrote, “we have to deal with human reality as a being which is what it is not, and which is not what it is.” Perry’s similar critical movement boils down to this: She takes up, affirms, opposes, denigrates, acknowledges and discards all of her positions so quickly, so seamlessly and so repeatedly that she destroys their natural sense and leaves us in a void, a Lacanian vacuum in which she draws from the same eerie power as a condemned Antigone, a space between life and death, the terrible place from which come both abominations and shattering beauties.

In a lecture in 1977 Michel Foucault charted the program of the physiocrats, an influential group of economic philosophers active in France in the 1700s. The physiocrats were concerned with famine; periodically the grain would run out in an area and people would starve to death. The mercantilist system that prevailed in France at the time limited grain storage (to prevent hoarding and profiteering) and forbade export and import (to prevent starvation caused by profiteering French grain merchants). The physiocrats argued that famine was an imaginary condition caused by artificial restraints on the free market. The opposition of surplus and famine was a chimera, a fantasy, and the government’s apotropaic struggling against it in fact made the fantasy real rather than averting it. An uncontrolled market approach would prove famine’s non-existence, they theorized, since freely moving grain would in and of itself control prices and availability even if a few people here and there starved to death.

The analogy with Perry’s album is clear—the stark difference between real and unreal, between affectation and genuine sentiment, similarly reflects a confused and superstitious fear of a condition that does not naturally or inevitably obtain. It takes the power and grace of Antigone to argue in such total terms. I admit that I have not completely processed the violently destabilizing import of the album. Yet what will come after Katy Perry? Who will enter the doors that she has flung wide, and what horrors will shamble forth? Or what beauties?