During his exceptional tenure as a creative force at Marvel Comics—including the immediate successor to Stan Lee as Marvel’s editor-in-chief—Roy Thomas had a hand in creating some of the most enduring, beloved and important characters in comic book history.

With the conception of cultural icons like Wolverine, Luke Cage and Iron Fist on Thomas’ resume, it may seem odd that the origin of one of his C-list supervillain creations from Prince Namor’s rogues gallery, Tiger Shark, would be of such interest to me. However, as someone with an abiding love for both swimming and comic books, the origin of the Tiger Shark character struck me due to its mixture of tragedy and improbability. In Todd Arliss, you have a rather self-centered athlete who managed to pull off one of the most unlikely Olympic feats imaginable, especially for a man who’d yet to achieve a super-powered state: He swept the gold medals in the swimming and diving events at the same Olympic Games, and then suffered a freak spinal cord injury while rescuing a drowning man.

Not only has such a far-fetched athletic accomplishment never even been attempted, but it’d be irrational for someone with a direct association with the sports of swimming and diving to even fathom its possibility once you understand the distinct differences between them. Simply, the most highly-competitive male divers are routinely shorter than 5’8”, while the average finalist in an Olympic Games swimming event has been trending in the 6’3” range.

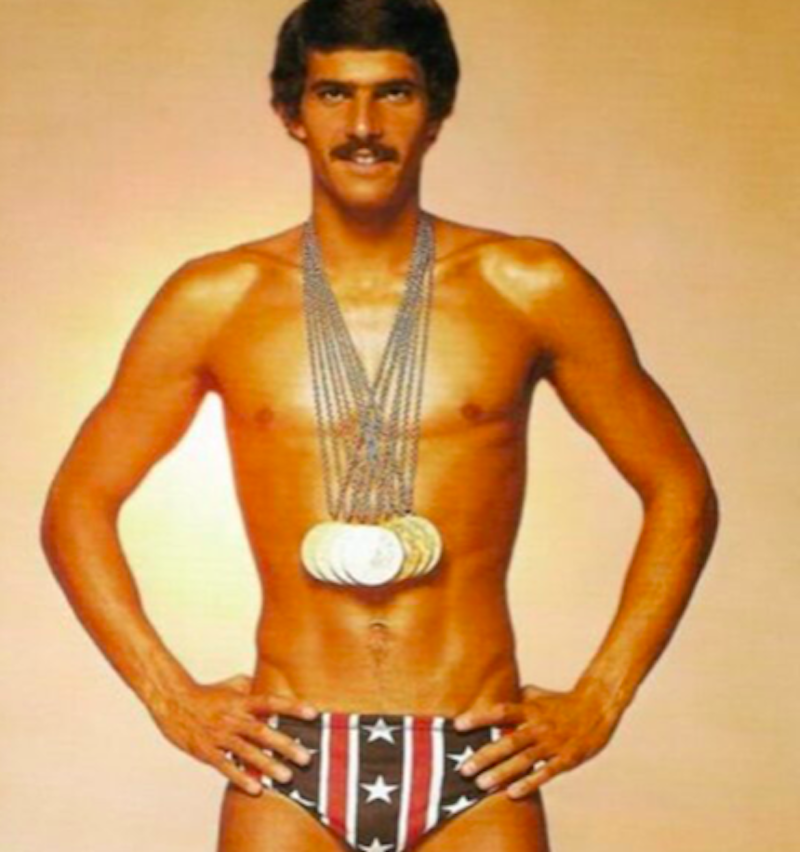

For what it’s worth, Thomas couldn’t recall what made him think it’d be possible for an athlete to achieve the daunting task of sweeping the swimming and diving events at the same Olympic Games, although Tiger Shark was created right around the time Olympic legend Mark Spitz was first speculating that it might be possible for him to win seven gold medals in swimming at a single Olympics.

“I'm afraid I don't recall any kind of Mark Spitz connection to Tiger Shark, but there could have been, if Spitz's claims were in the papers and on TV news at the time,” stated Thomas. “Sorry I can't give you any details, but it was a natural-enough backstory, and wouldn't have needed much of a nudge for me to come up with all the elements, even with Spitz.”

So was such unfathomable success the stuff of mere comic-book fantasy, or could Tiger Shark’s in-water successes possibly be replicated outside of the four walls of a comic book’s pages? In order to help me investigate whether or not it would even be remotely possible for the same athlete to simultaneously be ranked in the top 20 in the world in both swimming and diving—let alone capture gold medals in both sports at the same Olympic Games—I queried the swimming and diving coaches from the University of Florida.

Florida head swimming coach Anthony Nesty believed it would be virtually impossible for “The Tiger Shark” to ever be accomplished in real life, but conceded that he’d be willing to do whatever he could to land such an ambitious two-sport star in the NCAA program that employs him. “If it’s a special athlete, someone at that level is very unique, and there are only a handful of unique athletes out there,” said Nesty. “We call them ‘freaks.’ If that person can compete at that level, it would be good publicity for both the athlete and our program if we could bring them in. There have been athletes who have done swimming in the fall and then done other sports in the spring, so it has been done. If the kid is the right fit, we’d be happy to have them. At Florida, we want to compete in the conference and nationally. If that student athlete can help us win championships, it’s a welcome thing.”

It’s not surprising that Nesty in particular would nurture the notion of athletes performing groundbreaking feats. In 1988, Nesty shocked the world at the Seoul Olympics by defeating favored American Matt Biondi in the 100 meter butterfly by one one-hundredth of a second to become the first Black swimmer in history to capture Olympic gold in swimming.

Less optimistic that “The Tiger Shark” could ever be achieved was Florida diving coach Bryan Gillooly. Despite his diving accomplishments and general faith in the caliber of athletes who dive, Gillooly believed both the vast differences between the sports and the training requirements of each would pose insurmountable barriers to anyone attempting such a double-medaling feat. “It’s not possible, at least not to be top-20 in the world,” insisted Gillooly. “You’d have a better chance finding a diver who could swim as opposed to a swimmer who could dive. It’s two very different disciplines. Many high school divers will swim competitively for their high schools. I even swam in a couple races in college, but that was the coach putting me in a relay and just asking me not to false start so that we could secure the points. A diver I grew up with—Mark Ruiz—was an Olympic diver and finalist; he was close to being state champion in the 50 free. Shorter races that don’t require as much endurance and therefore don’t require as many hours in the pool, maybe you could toy with that a little bit more, but once you get past 100 yards or meters, you don’t have the time to put in to get that kind of endurance as a diver.”

The requirement of allocating training time to be competitive on the world stage is a crucial element to consider. In the case of the Florida coaches, they have to adhere to an NCAA-imposed limitation of 20 hours per week of coached practices with their athletes, although teams do have protocols for nimbly sidestepping that barrier by permitting athletes to train on their own time, or enabling them to pay dues to join the private swimming and diving clubs that often train in the very same pools that their university teams practice in.

“You can be a world-class diver by training 20 hours per week, but you’re going to go up against the top level athletes from other countries like the Chinese, who are training double that length of time at least, if not more,” said Gillooly. “You can be in the mix, but at some point, you’re going to have to log extra hours somewhere. You can be competitive on the world level with the 20 hours per week—especially if you get the most out of those 20 hours—but you’re going to be at a disadvantage against someone who’s training 40.”

That sort of time commitment would be a problem for a University of Florida diver who also sought to follow the grueling practice schedule required by Nesty for swim team participation—a schedule that has been followed by Olympic greats like Ryan Lochte and Caeleb Dressel, and which also looks to get the most out of the time limitations imposed by the NCAA.

“Even back in 1988, we had nine water workouts each week,” said Nesty. “We also had three weight practices and two dryland practices every week, where weight training sessions were an hour, and dryland workouts were 45 minutes max. So that’s a full week of 14 training sessions.”

Then Nesty compared the physical toll that training as a diver would have on his swimmers. “The impact that divers go through every time they hit the water is very tough on their bodies,” sympathized Nesty. “Swimming is a grind, but it’s low-impact. On the other hand, diving is high-impact. I’ve seen divers totally eat it in practice and during meets. That’s no fun. You’re also talking about disciplines that are complete opposites. They’re both technical, but diving is far more technical.”

After a moment of reflection, Nesty added, “I’ve always said that in order to be the very best at something you have to specialize in it. It would be incredibly hard to specialize in two very different things and be among the best in the world at both of them.” And according to Gillooly, the combination of the time it takes to achieve the precise level of technical proficiency required by elite divers and the general time allocation it takes to become world-class in a sport will forever ensure that “The Tiger Shark” will forever remain an achievement isolated to the fantasy world of comic books, and to Roy Thomas’ aquatic supervillain born in the late-1960s.

“I do think a diver could translate to swimming a lot easier; we have to swim just to get out of the pool,” said Gillooly. “So we do have that little bit of swimming built into our everyday practice. However, if a diver wants to be one of the best in the world, that time it takes to get from the board to the side of the pool is probably the only swimming they should ever be doing in a structured practice.”