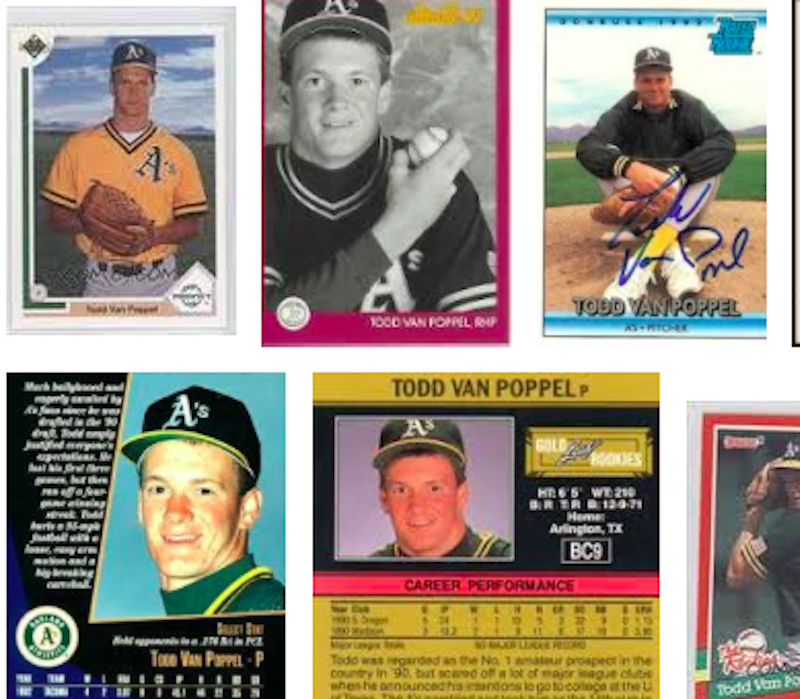

About 25 years ago, hundreds of fans would flock to weekend baseball card shows to buy up as much cardboard as they could. They took risks, shelling out $60-$100 ($106.70-$176.78 in 2016 USD) for Jose Canseco and Darryl Strawberry rookie cards, both of whom were on Hall of Fame tracks earlier in their careers. Heck, 19-year-old Todd Van Poppel’s 1991 Upper Deck rookie card sold for three dollars ($5.30 in 2016 USD) apiece before he had ever even pitched in a big league game.

The hype and market for baseball cards of the late-1980s and early-90s led sports fans to believe they were a sound investment. But anyone trying to retire off their investment or even recoup what they put in will realize all they bought was overpriced cardboard. At 60 cents ($1.07 in 2016 USD) for a pack of 10 cards became a penny stock investment for sports fans. And like most penny stocks, the investment failed miserably.

During the “junk wax” era (1987-1993), marketing and production of baseball cards increased and with it, so did the demand to the point where counterfeits were a concern. But how large was the supply? As Dave Jamieson’s book, Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession notes, there were 81 billion cards printed per year at its height. An April/May 2010 issue of Beckett Baseball Magazine lists 7851 mainstream baseball cards from several companies. If those were the only cards made that year and each company produced the same number of them, that would mean there were nearly 10.7 million of each card produced.

At the time, there were 26 MLB teams with 25 players on the roster—which translates to 650 men on big league rosters for most of the season. Of course, there were also manager’s cards and team cards. But even someone like Steve Lyons, who was not much more than a replacement-caliber player in his nine-year career, had five mainstream cards in 1991.

Superstars of the time—some of whom are now Hall of Famers—had more than 10 different cards printed in the year. That’s potentially over 100 million cards per year of the same player. It’s unfortunate fans-turned-investors focused more on novelty than inflated production numbers and prices.

So what about those Canseco and Strawberry rookie cards that could warrant a Ben Franklin in 1991? Now, they typically go for a couple dollars at most. Why would they be worth anything when there’s so many of them? They’re not rare and people didn’t seem to understand that during the “junk wax” era. They didn’t realize card companies were just trying to profit off the general public.

Topps (or the other, now-defunct card companies) doesn’t care what those cards are worth now. They sold cards for a few cents each, which was even a bit overpriced back then. After all, those companies needed to make a profit too. The value came from what people were willing to pay for cards. Plus, card shops were go-betweens that marked prices up further because they paid a rent/mortgage selling baseball cards, as absurd as that may seem now. With the Internet as America’s preferred marketplace now, there’s no longer a need for that markup.

It's difficult to find someone who wants to buy those old junk wax commons except the occasional shark at a card show offering up one dollar for 1000 cards or five dollars for 5000 cards. And yes, those $3 Van Poppel rookie cards would be in this category. Not worth the time and gas. And no, the few remaining brick-and-mortar card shops don’t want anything to do with more junk wax cards. It’s astounding they still exist. It's tough on former collectors who paid six cents per common card to give them away for a 10th of a cent. With inflation, that's over a 99 percent depreciation in value. Anyone who lost out on their baseball card investment can take it as a lesson: don’t invest in fads. Once the novelty wears out, so will the market—especially when mass-produced.