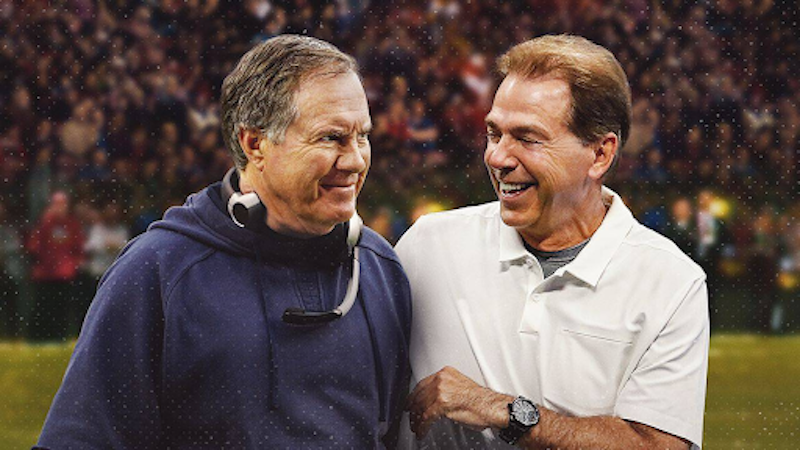

In the annals of American football, the names Nick Saban and Bill Belichick shine with an intensity that few others can match. Both of Croatian-American descent—they’re perhaps the two greatest Croatian-Americans of all time—these coaching giants have dominated the football landscape for the past 30 years. Saban, with his collegiate success at LSU and Alabama, and Belichick, with his NFL accolades, seemingly represent two sides of the same coin. However, a closer examination reveals that Saban's career, in many aspects, has far outstripped that of friend and mentor Belichick.

One of the most compelling arguments for Saban's superiority lies in his unparalleled success across multiple Division I football programs. Unlike Belichick, who has spent his NFL career primarily with the New England Patriots, Saban’s left his indelible mark on four different college programs. At each stop—the University of Toledo, Michigan State, LSU, Miami (in the NFL), and finally Alabama—former Kent State cornerback Saban not only improved the team's fortunes but often turned them into world-beating powerhouses (his 1990 Toledo and 1999 Michigan State squads, each of which went 9-2 in the regular season, are all too easily overlooked). He could win with MAC players, Big Ten players, and is the man who, alongside rival Urban Meyer at Florida, turned the SEC into America’s wealthiest college football conference.

Further bolstering Saban's claim to the coaching throne is his ability to win national titles with different teams. He achieved this rare feat with both LSU and Alabama, showcasing his ability to build championship-caliber teams from different foundations; the ‘03 Tigers championship squad, while boasting a few quality NFL players, was nothing like the football factory that his subsequent Crimson Tide teams became. This success across various programs starkly contrasts with Belichick's career, which, though immensely successful, has been largely tied to one franchise and one quarterback, Tom Brady, whose geriatric Super Bowl run with Tampa Bay proved he could win anywhere.

Saban's prowess in developing pro talent represents another feather in his cap. He has consistently turned out NFL-ready players, particularly from skill positions, and ended Alabama’s long Heisman Trophy drought in the process. Second-generation star Mark Ingram Jr. (who won in 2009) and 6’3”, 245-pound Derrick Henry (2015) are prime examples, both flourishing under Saban's guidance to clinch college football's most prestigious individual award. Their success in the NFL further highlights Saban's role in their development. Ingram, with his powerful running style, and Henry, known for his extraordinary blend of size and speed, each enjoyed solid pro careers, with the latter racking up a 2000-yard rushing season along the way.

The number of Saban's former players selected in the NFL Draft is staggering. From 2009 to 2023, over 90 players from Alabama have been drafted into the NFL, with numerous first-round picks. This includes standout names like Julio Jones, Amari Cooper, and Minkah Fitzpatrick, who’ve not only transitioned seamlessly to the professional level but have also become stars in their own right.

More than that, Saban has shown he can win with various quarterback archetypes, from game managers to dynamic playmakers. Career backup AJ McCarron, who led Alabama to two national titles as a starter, exemplifies the prototypical NFL-level game manager who has thrived under Saban's system. Conversely, Tua Tagovailoa represents the more dynamic, playmaking quarterback, steering Alabama to a national championship with his unforgettable second-half performance in the 2018 College Football Playoff National Championship and currently powering the Miami Dolphins high-octane offense. This ability to adapt his system to different quarterback styles and still repeatedly achieve the pinnacle of success is a testament to Saban's diverse coaching abilities. Meanwhile, Vinny Testaverde, Matt Cassel, and Jimmy Garoppolo—all above-average signal-callers—ultimately enjoyed less postseason success under Belichick than they would elsewhere. Not only that, but players drafted and developed by Belichick, outside of a few superhuman talents like Brady and gigantic defensive lineman Richard Seymour, have shown a propensity for faltering as soon as they left Foxboro.

While Saban’s NFL run was far less illustrious than his other achievements, a closer look reveals that this two-year foray with the Miami Dolphins was not the disaster many perceive it to be. In fact, his NFL record mirrors the league-average performance that characterized Belichick's tenure with the Cleveland Browns. In fact, the relative parity in their professional records when games featuring Tom Brady are excluded all but closes the gap between their perceived coaching abilities at the professional level.

The manner of their respective departures (or lack thereof) from coaching is also telling. Saban retired from coaching Alabama with dignity and almost at the pinnacle of success. In contrast, Belichick's tenure post-Brady has been marked by an unquenched thirst to surpass Don Shula's NFL wins record. This obsession, while a testament to his competitive spirit and a disdain for Shula tied to the old coach’s criticism of Belichick’s assorted coaching scandals, also highlights a stark difference in their personalities and approaches towards their legacies. Saban, by contrast, is only a handful of wins away from Bear Bryant’s Alabama record — yet that didn’t stop him from calling it a career.

In discussions of coaching greatness, Shula's name proves inescapable. A first-generation American of Hungarian descent, Shula's coaching career is often seen as the standard by which all others are judged. Shula—a capable cornerback for Paul Brown’s Cleveland Browns and Weeb Ewbank’s Baltimore Colts—made six Super Bowl appearances across four decades spent coaching the Colts and Dolphins, winning twice (doing so in 1972 with an undefeated record that Belichick, leading his own best team in 2007, proved unable to match).

Shula’s ability to evolve his coaching style over the years is something Belichick and Saban have emulated to varying degrees of success. The longtime Patriots coach focused more on tweaks and bargain-bin player discoveries (e.g., NCAA heavyweight wrestling champion Stephen Neal, MAC quarterback Julian Edelman, Hall of Fame tackle Jackie Slater’s undersized son Matthew, teeny-tiny Chadron State running back Danny Woodhead) that would complement the singular Brady. Meanwhile, Saban's career trajectory and continuous evolution more closely mirror the adaptability and consistent success that defined Shula's career, which was characterized first by punishing defenses in the 1960s and 1970s and then a wide-open passing game spearheaded by Pitt Panther Dan Marino in the 1980s and 1990s. Shula’s overachieving 1982 Dolphins, who lost a somewhat close Super Bowl to Joe Gibbs’ Washington Redskins, were quarterbacked by David Woodley—a good player like any pro athlete, but quite possibly the worst starting quarterback in NFL championship-game history.

Although Belichick's achievements in the NFL are significant, the verdict is clear: Saban has done more in more places. On top of that, his dignified exit from coaching underscores the grace with which he has handled his success, a stark contrast to Belichick, who would probably take a tough loss to a rising coaching star, particularly an obnoxious win-at-all-costs rival like Jim Harbaugh, far more personally than Saban did. Of the two Croatian-Americans who once towered above all their coaching rivals, the longtime Alabama leader loomed far larger than the petty tinkerer Belichick, whose reputation will almost certainly continue to shrink as he chases Shula’s records.