What a difference 10 years can make. Last July, Bud Selig, the Major League Baseball Commissioner who oversaw the relocation of the Montreal Expos to Washington after the 2004 season, was asked about two exhibition games held at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium in March of 2014. The games had drawn a total of 95,000 fans, most of them under age 35. As quoted in the Toronto Star, then-Commissioner Selig said: “It did make a great impression. I was impressed and I talked to a lot of people there. They have much work to be done, but that was very, very impressive, no question about it.” And: “I wish them well and I think they could be an excellent candidate in the future, no question about it. That was very impressive, very impressive.”

By “excellent candidate” Selig meant Montreal could be a candidate for a new team, whether by expansion or another franchise relocation. By the time the Expos left in 2004 Selig was widely seen by fans as hostile to the team, so his words were sweet to Montreal baseball partisans hoping to get a new team. For the first time Selig admitted the possibility of baseball returning on a permanent basis.

It has to be said that Selig himself didn’t attend the exhibition games. And usually when a commissioner of a major league sport talks openly about how wonderful a market a city would be for his sport, it means that they’re trying to shake down somebody in one of their existing markets—a state or municipal government that doesn’t want to go along with plans for a new stadium, for example. Coincidentally, the troubled Tampa Bay Rays franchise is trying to get out of their lease with the government of St. Petersburg, Florida (another squabble is ongoing in Oakland). In October last year, about three months after Selig’s comments, the New York Daily News published an article citing anonymous “sources” who claimed that Rays’ owner Stuart Sternberg had discussed the possibility of moving the team to Montreal with “wealthy Wall Street associates.” In December, the Tampa Bay City Council rejected a deal that would have let the Rays look in the Tampa area for sites for a new stadium. Could the Rays end up finding a new home in Montreal?

People in Canada have working on laying groundwork, whether for the Rays or another team. Former Expos star Warren Cromartie founded the Montreal Baseball Project late in 2012, when the chances of landing a franchise seemed nil. Over the next few months, some voices in the sports media, notably Keith Olbermann and Jim Caple, began to openly speculate about baseball returning to Montreal. On March 20, 2013, Cromartie’s MBP launched a feasibility study which, after a few months of crunching numbers, concluded that under certain circumstances a new Montreal major league franchise could succeed.

By the time the report was released, the 2014 exhibition games had been announced. As noted, those games were a success, and at the 2014 All-Star game Selig made his favorable comments. Stories about Montreal baseball continued turning up: a group of Expos fans traveled to New York to take in a Mets game and show their desire for baseball to come back to Montreal. Another pair of Montrealers traveled to every MLB stadium over the course of the season to watch games and talk about the Expos. In January, 2015, Montreal mayor Denis Coderre, an outspoken proponent of the idea, announced a new “Baseball Plan” for the city which included $11 million over three years to build and improve baseball diamonds in city parks, along with promoting youth participation in the sport.

A few days after that, Selig officially stepped down as MLB Commissioner and Rob Manfred took over. In a wide-ranging interview with The New York Times just after taking office, Manfred said: “Look, I think Montreal helped itself as a candidate for Major League Baseball with the [exhibition] games that they had up there last year. It’s hard to miss how many people showed up for those exhibition games. It was a strong showing. Montreal’s a great city. I think with the right set of circumstances and the right facility, it’s possible.”

At the same time, he stated that he didn’t see imminent expansion in the cards. So perhaps he was being honest about Montreal having helped itself, and then again maybe he was taking a shot across the bow of the Tampa City Council. Or both; he could’ve been impressed with Montreal’s showing, and also realized it’s a fine stick to beat Tampa with. On a practical level, how much stock should be put in the Montreal Baseball Project’s study? How likely to materialize are the conditions it forecasts—such as a new stadium in downtown Montreal? And if baseball in Montreal could work now, why did it fail the first time?

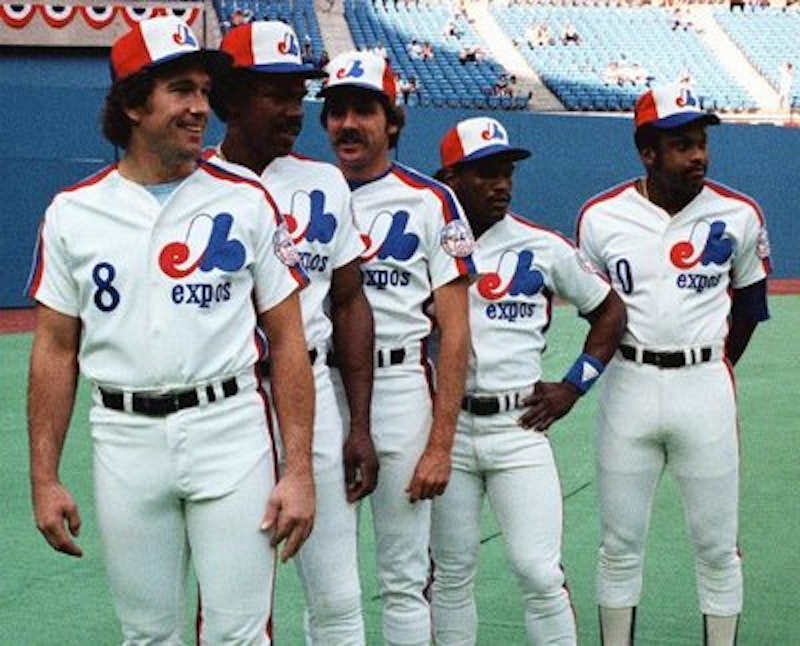

I think a lot of different things came together to bring about the Expos’ move, and you have to go back a long way to get the whole picture. At one point in the early 80s, the Expos were phenomenally popular, with a higher yearly attendance than the Yankees. They were young and promising, boasting names like Cromartie, Gary Carter, Tim Raines and Andre Dawson. But problems started to show like cracks in a dam—more and more of them, growing bigger and bigger over time. Some were unavoidable, but others could have been fixed. They weren’t, and eventually the whole thing became unsalvageable.

As a former Expos fan, I think back to the day my fourth grade class toured the Olympic Stadium, the Expos’ home field for the previous four years. That happened to be the day in 1981 that the Expos were playing a decisive playoff game against the Los Angeles Dodgers. Originally, the game had been scheduled for the day before, but bad weather postponed it to that Monday afternoon. In my memory I walk in my parents’ front door and turn on the TV to watch the end of the do-or-die playoff game that could send the Expos to the World Series—and see Dodgers’ centre fielder Rick Monday knock a tie-breaking two-out ninth-inning home run over the same fence my class had passed by just a couple of hours before. The Expos couldn’t do anything in their half of the inning, and the season was over.

Expos fans still call that day “Blue Monday”; Dodger blue, Rick Monday, the Monday start, the blue feeling of elimination. That year’s Expos team was considered by a lot of people to be the best team in baseball; the Dodgers, on the other hand, went on to beat the Yankees and win the World Series. If it had been the Expos, what then?

As it was, things didn’t look obviously disastrous. The attendance was strong—the Yankee-beating years of 1982 and 1983 followed. But there were some deeper structural problems. To start with, the promising young team wasn’t winning the way people had thought they would, hobbled (it would later emerge) by a bad clubhouse culture and issues of substance abuse. That led to bad trades, alienating the fan base. Meanwhile, the bloom soon came off the dubious rose of the Olympic Stadium; built in 1976 and paid for by the province of Quebec and (mainly) the city of Montreal, cost overruns sent the price sky-high, while the projected retractable roof was left un-built for years, and then, when completed, never worked. As well, a 1980 referendum on whether Quebec should secede from Canada led to years of political uncertainty for Montreal and thus tough economic times. Combined with a low Canadian dollar, this took a toll. Once baseball owners’ collusion in keeping salaries down was ended in the late 80s, player salaries (paid out in US dollars) began to explode.

In 1989, Expos GM Dave Dombrowski made a number of moves to try to shore up the team and win the division. Among his deals was a May transaction in which he brought in veteran pitcher Mark Langston in exchange for three prospects. The deals didn’t work; players reportedly were irate at the Langston deal putting pressure on them to win. The Expos folded as the season got tougher, a longstanding problem for the team, and finished the year at exactly .500. Langston ended the season 16-14, although modern advanced stats suggest he had quite a good year. But one of the prospects the Expos gave away in the Langston deal, a young beanpole of a pitcher named Randy Johnson, would go on to a brilliant career elsewhere. And: dispirited by the team’s failure, majority owner Charles Bronfman decided to sell the club.

This triggered a long search for a new owner. In mid-1991 a consortium led by Expos President Claude Brochu closed a deal for the team. The group did not have deep pockets, meaning the Expos would have a limited payroll. But a superb scouting and development system was producing a new generation of promising young players, and when Felipé Alou was installed as manager during the 1992 season, the team began to win. They won even more in the 1993 season—after which management took the at-the-time-controversial decision to trade an emerging star infielder in Delino DeShields for a young fireball-throwing relief pitcher who the Expos thought could become a starter: Pedro Martinez. It worked, and helped set up the 1994 season.

That year’s Expos featured Martinez, Moises Alou, Larry Walker, Marquis Grissom, John Wetteland and Ken Hill, just to name a few. As an Expos fan I’d never seen a team like it. They won games not just regularly, but spectacularly; and not just spectacularly, but with a kind of insouciance. They’d go into the seventh or eighth or even ninth inning down a few runs, get up to bat, and casually knock in hit after hit until they’d taken over the game and put it out of reach. For maybe the first time, an Expos team was truly elite, not just by the numbers, but in sheer all-around player-for-player talent.

So, naturally, it all came crashing down.

On August 12 a strike by the players began that ultimately wiped out the rest of the season and the playoffs. At the time, the Expos were six games in front of their nearest competitors, the Atlanta Braves. I remember thinking at the time that the strike was the worst of all worlds for the Expos: not only did it wipe out any chance for a post-season appearance, but the final deal featured only some relatively minor revenue-sharing, not a hard salary cap.

As a result, the Expos made a series of personnel decisions widely regarded as fire sales. By the time the 1995 season began, they’d parted ways with Hill, Walker (who’d go on to be the National League MVP in 1997), Wetteland (the 1996 World Series MVP), and Grissom (the 1997 American League Championship Series MVP). Walker, a Canadian who left as a free agent, stated he would’ve taken a pay cut to stay with the Expos, but the team never got in touch with him. Unsurprisingly, the team lost fans, and the bleeding grew worse when they opted not to sign Moises Alou after the 1996 season, then traded the Cy Young–winning Pedro Martinez in 1997. It was an incredible amount of talent for any team to lose in such a short time, even though the Expos scouting was producing yet more young prospects, among them Rondell White, José Vidro, Orlando Cabrera and Vladimir Guerrero.

Was the ‘94 strike the turning point for the Expos? In hindsight it looks like it. But there were larger structural issues as well. Another provincial referendum in 1995 dealt a blow to Montreal’s economy, and the Canadian dollar was also dropping (by August 1998, one Canadian dollar could be bought for just over 63 American cents). And, crucially, in a sport increasingly driven by broadcast revenue, the Expos weren’t able to make much money off of TV and radio: the Blue Jays’ World Series wins, and the Expos’ own problems, led to Toronto becoming by far the more popular franchise across Canada—in turn leading the Expos to seemingly write off Canada outside Quebec as a possible fan base. A World Series win in 1994 might have turned the tide, but for how long?

As it was, the team tried to gather support for a new downtown stadium; the Big O, as the Olympic Stadium was known, was generally agreed to be a terrible place to watch a baseball game. Built far to the east of the city’s core, with a roof that still didn’t work, it was literally falling to pieces—in 1991 a 62-ton concrete slab had fallen onto an upper walkway. But the provincial government was unwilling to put money into a stadium. Maybe a Series win would’ve led to more popular support, and the politicians would’ve taken a different stance. Maybe not. Either way, in 1999 the frustrated local ownership group sold a large chunk of the team to art dealer Jeffrey Loria, a buddy of Bud Selig’s.

Loria, along with his sidekick and stepson David Samson, soon expanded his initial ownership stake and became the curse of Montreal baseball fans. Some have argued that the two men didn’t initially intend to scuttle the franchise, but from the outside it looks like they made the decision fairly early on. In 2000, annoyed at what they viewed as lowball offers for local broadcasting contracts, they refused to sign any local TV or English radio deals. For the first time in decades, Expos broadcaster Dave Van Horne (to my mind one of the great baseball voices) was not to be heard on Montreal radio.

When another deal to finance a new stadium fell through, the writing was on the wall. After 2001 the team fired Felipé Alou, still popular among the dwindling fan base, and MLB teams voted 28-2 to contract the Expos and the Minnesota Twins. Court action in Minnesota prevented the contraction, and Loria sold his stake in the Expos—to his friend Bud Selig and Major League Baseball, receiving in exchange ownership of the Florida Marlins. On his way out the door, Loria took everything from the Expos front office that wasn’t nailed down, including the coaching staff, scouting reports and the team’s computers. (This, despite an ultimately unsuccessful racketeering suit filed against him in Miami by his former Expos partners.)

By this time things got weird. Forced to operate the team due to the Minnesota legal decision, Selig was open about his desire to move the franchise, and scheduled a quarter of the Expos’ home games in Puerto Rico. Still, under a hastily-installed staff that included GM Omar Minaya (the first Hispanic General Manager in Major League history) and coach Frank Robinson, the Expos were reasonably competitive in 2002, and in 2003 were still in contention for a wild-card playoff spot heading into September. At which point MLB refused to allow Minaya to call up minor-league players, in an ostensible economy measure, and the team faded. The 2004 squad went nowhere as well—except Washington.

The official announcement that the team would move south for 2005 came on September 29, 2004. The Expos played their last game in Montreal that night, drawing a crowd of over 30,000, including me. Typical of Major League Baseball, the Expos weren’t even allowed to finish their existence in front of a hometown crowd. It was a blowout loss, and the post-game ceremonies were, as you might expect, subdued. A few days later the Expos played their final game at Shea Stadium. And that was it. The surprise wasn’t that the team regularly only drew a few thousand people to home games; the surprise was that so many people still turned up, after almost a decade of unrelenting bad news—fire sales, mockery, endless speculation about contraction or relocation.

Could a new major league franchise work in Montreal? Even the Montreal Baseball Project’s study admits the conditions would have to be right. Strong ownership, a downtown stadium, and ticket prices at about the Major League average would all be needed—as would a contribution of over $300 million from various levels of government.

Which actually might not be impossible. The provincial government recently spent $200 million on a new hockey stadium for Quebec City in an attempt to attract the NHL back to the provincial capital (the municipal government of Quebec City contributed another $200 million). You can’t exaggerate the provincial government’s ability to show contempt for the city of Montreal, but even so it’d be difficult to justify supporting the Quebec City project without contributing to a Montreal stadium if and when a new team became a real possibility.

At which point the question becomes: how would Montrealers, and Quebecers, react to the government subsidising a new stadium? Tough to say; but polls show both residents and Montreal-area corporations are in favor of baseball returning to Montreal—one recent survey says 70 percent of people and 81 percent of businesses would like to see a team back in town. Other indications look good as well. The population of the Montreal area recently topped four million, up half a million or so from 2004. The economy is much stronger, notwithstanding a recent dip in the dollar. Baseball has a more forgiving playoff format, which might’ve helped some of the Expos teams of the 80s and early 90s. And, crucially, the Canadian broadcasting landscape has changed dramatically, with two different nationwide all-sports networks in both official languages. I can see a new team working out; I note that Minnesota, who 14 years ago was supposed to be contracted out of existence along with the Expos, is now doing fine.

It has to be said, too, that Montreal has a long history with baseball. The Montreal Royals were founded in 1897, and one version of the team or another was in operation up through 1960. The top minor league affiliate team of the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1940 on, in 1946 they won the International League championship thanks in part to Dodgers’ prospect Jackie Robinson, who played his first MLB-affiliated baseball with the Royals. More than is commonly realized, baseball has been a part of the city’s culture for a long time.

Realistically, it’ll be a long time before Major League Baseball returns to Montreal. The Expos’ move to Washington is the only franchise relocation in the past 40 years, so it’s unlikely the comparatively minor contretemps in Tampa or Oakland will result in a team changing cities. If baseball does return, expansion would be more likely, and that doesn’t seem an immediate possibility.

Still, I hope it happens. My grandparents followed the game when I was younger, and so I grew up a fan; I’d like to be able to take my nieces to a game in downtown Montreal to root for the home team. I don’t know if that’ll ever come to pass, and if it does it’s more likely to be with my nieces’ kids. But I miss the Expos, even if I don’t miss the people who run Major League Baseball.