Remember how much you cared about the fads and trends you liked in middle school? No one obsesses like a pre-teen struggling through puberty, because no one else is so painfully in need of something to identify with. Nothing makes sense for kids at that age. You know you’re not supposed to be a kid anymore, but all you really understand about maturity is a shimmering mirage of the real thing. In that chaotic search for self-esteem we all latch onto anything that gives us definition and acceptance. Inevitably this something is simple, and arbitrary, and we love it desperately. When so much of the reality inside you and around you is constantly changing, your idols become your anchors.

Maybe you idolized a band, or the way the popular girls dressed, or a certain magazine. To my regret, I idolized the Baltimore Orioles. The Orioles were the only major sports team in town at that point: baseball’s long season, arcane rules, and peculiar attention to statistics provided a ready obsession that distracted me from the inescapable shame of being in seventh grade.

I was not alone in this obsession, which was sort of the point. The Orioles have a special place in the hearts of the people of Baltimore. We do strange things to support our team, like scream “O” in the middle of the national anthem. In many ways, their history is our history. Baltimore, as a de facto rust belt city, suffered a slow economic decline after World War II. The Orioles, after assembling some of the best teams ever during the late 60s and early 70s, gradually lost ground to the changing economics of baseball.

The O’s last won the World Series in 1983, when I was two months old. My mother assures me that I was watching when a humble young shortstop named Cal Ripken caught the last out. It would be 13 years until they reached the playoffs again. In the meantime, as I meandered through childhood, the Orioles suffered. In 1988 they set a record by losing 21 games in a row to start the season. Between 1990 and 1996 the Orioles let pitchers Curt Schilling, David Wells, and Kevin Brown leave the organization, a trio that has combined for 616 wins, six World Series championships, one perfect game, and one no-hitter.

Sure there were a few exciting moments. Camden Yards defined the retro stadium era when it opened in 1992. Cal made everyone forget about the players strike when he broke the record for consecutive games played, personifying working-class Baltimore in the process. But for the most part, they weren't an easy team to root for.

When the 1996 season kicked off I was finishing up sixth grade. I was gangly, crippled by the presence of girls, and had just started shaving. I really needed the Orioles. And that summer, they finally came through.

Behind the strength of Robbie Alomar, B.J. Surhoff, Cal, Mike Mussina, and a resurrected Eddie Murray, the Orioles made it back to the playoffs. The experience couldn't have been more glorious. The team bombed balls out of the park in the halcyon days of blissful steroid ignorance, setting a record for the most home runs hit on the road in a season.

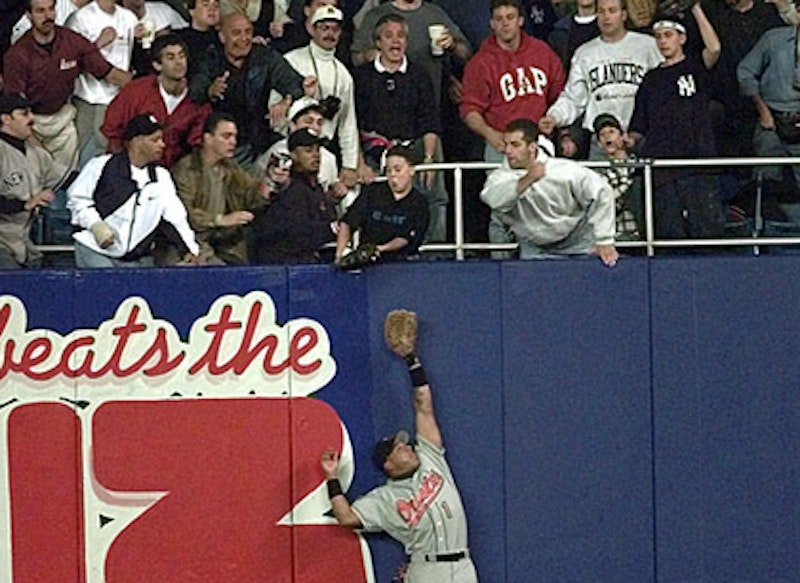

The Orioles dismantled the Indians in the first round, setting up a seven game series with the Yankees. This was the ultimate test, our chance to slay the most hated team in the sport. The series started in New York. I stayed up late with my dad and my brother watching the Os take a 4-3 lead into the eighth inning. A smarmy rookie shortstop named Derek Jeter hit a long drive to right field, but it looked like the right-fielder Tony Tarasco could make a play. He backed up to the wall, and just as he was preparing to look the fly ball into his glove, Jeffrey Maier, a pimply middle schooler like me, reached over with his glove and snatched the ball away. It was as clear as day. (Watch it here.) Tarasco immediately pointed to the offender, but the umpire ruled it a home run. Tie game. The Orioles manager raged in a Sisyphean effort while Yankee fans shook that damn kid’s hand and bought him hotdogs. The Yankees won the game in extra innings and took the series in five.

I was crushed. The one sure thing in my life had evaporated. The world had proven that it was not merely indifferent to my life, but was actively conspiring against me, and using some New York City punk to do it. That kid, meanwhile, was treated like a hero, going on Letterman and receiving a key to the city as his team won the World Series.

I was stuck trying to make sense out of my now-rudderless existence while my doppelganger lived the dream. The whole experience psychologically branded my young brain, horribly conflating my Orioles fandom with my quest for self-understanding. It would take me many years to get over it.

The Orioles made the playoffs again the year after but it was never the same. 1997 would be our last winning season. As the Yankees—and later the Red Sox—spent astronomical amounts of money on Rolls Royce rosters, the Orioles overpaid for a used rental car in a sad attempt to keep up. Every year owner Peter Angelos hobbled the team with long-term contracts for crappy veterans, teasing fan expectations while consistently losing most of the games. The waste and profligacy reached comic proportions, mocking the blue-collar success of past Orioles teams. Albert Belle was paid $39 million over three years to not play after retiring due to a bizarre hip injury. Some major league impersonator named David Segui made $28 million while playing, on average, 50 games a year.

As I grew up I kept buying into the false hope. I needed the Orioles to be good again before I could bury my seventh grade sense of self. It never happened. While the O’s continued spending millions on the walking embodiments of mediocrity, the rest of baseball changed. New management styles took over. Smart, well-run organizations with half the payroll of the Orioles kept making the playoffs.

2005 proved to be a turning point. Before the season five players were dragged in front of Congress to testify on steroid abuse. Two of them were Orioles—recent addition Sammy Sosa and Rafael Palmeiro, one of the few vestiges from the last playoff team. Raffy made me proud during those hearings, emphatically pointing at his questioner as he swore he never used steroids. The team then seized first place for 62 days straight during the first half of the season. For the first time in a decade I felt a tentative confidence that the Orioles were a good ballclub.

Fate, however, was not done toying with my fragile and complex relationship to my team. Only two weeks after collecting his 3000th hit, Raffy became the first prominent major leaguer to test positively for steroids. At the same time the team suffered an epic collapse, led by Sosa, a suspected user and one-time 60-home run hitter who could barely hit the ball out of the infield. Just to make sure the hitters didn’t get all the attention, overweight pitcher Sidney Ponson was arrested for DUI three weeks after Palmeiro was busted.

That summer, as countless embarrassing stories about the Orioles blanketed the sports media, I realized that they had become the joke in our relationship. The Orioles needed me far more than I needed them, an understanding that liberated my middle school attachment. They were the shameful ones, the needy ones groping for an identity. I had finally put them in the proper perspective, and it only took the baseball equivalent of Greek tragedy to do so.

One final act remained in the form of Jeffrey Maier. Maier had gone on to play baseball in college. In 2006, as the Orioles looked to move past the worst year in franchise history, there was talk that the team might actually draft Maier into the organization. This was flirting dangerously with baseball superstition. Bringing in the kid that started a decade of losing might have cleansed the Orioles, but it could just as easily have cursed us for another 10 years. The Orioles didn’t tempt the baseball gods and stayed away.

I like to think that rejecting Maier cleared away the ghosts of the past enough to start a legitimately new era in Orioles baseball. Last offseason the team traded away their best pitcher and a steroid tainted slugger for prospects. They’re actually rebuilding for once, committing to the baseball equivalent of going through puberty. I know they’ll feel self-conscious and embarrassed as they go through awkward growing pains. I’ll be the rock this time. I’m there for you, Orioles. Maybe I’ll treat you better than you treated me.