As many times as a sports melee or a classic dust-up has been referred to as a “Pier-Six brawl” by the play-by-play announcer or a fight reporter, it might come as a surprise that somewhere there was a real Pier Six where one or more legendary brawls truly took place.

The term “Pier-Six brawl”—along with variants like “Pier-Six fight”—has been widely employed to refer to hard-fought boxing contests for nearly a century, and it was inserted into the lexicon of professional wrestling by legendary announcer Gordon Solie to reference any of the contests that resulted in both of the participants sporting a “crimson mask”—one of Solie’s favorite descriptions of a blood-drenched face.

A panel from the comic strip “The Gumps” in 1949

The original Pier-Six Brawl took place at Pier Six… or at least a location that was casually known by that name. However, with all of the piers in existence along all of the waterways in the world, how can we isolate which pier was the sixth so that we can identify the infamous brawl that took place upon it?

According to a story relayed to Boston Globe reporter John Ahern by boxing historian Nat Fleischer—also one of the founders and original publishers of The Ring Magazine—who conveniently happened to be a New York resident born in the late-1800s, “Pier Six” wasn’t a reference to the sixth pier at a specific location.

“In those days they were just numbering the piers of the Hudson,” explained Fleischer, referring to the mid-1850s. “‘No. 6’ was painted on the building facing the water. It was easier to refer to ‘Pier Six’ than ‘Amos Docks.’ So a rough, unskilled bout became a Pier-Six brawl, and the name was adopted by writers of the day to describe it.”

Fleischer reasonably identified the Amos Dock as the “Pier Six” that’s still referenced to refer to brutal slugfests, but what about the brawl that inspired the term? For the most logical answer to that question, we travel back to 1854 and examine one of the events that inspired the film Gangs of New York.

Prelude to the Pier-Six Brawl

Not only was John Morrissey a politician and a member of the corrupt Tammany Hall political organization that ruled New York City, but he also held a tenuous and disputed claim to the title of “American Bare Knuckle Fighting Champion,” having defeated recognized champion Yankee Sullivan in October of 1853 under outlandish circumstances that would make a modern professional wrestling fan blush. By the account published in The New York Herald, Sullivan outfought Morrissey throughout the entire 37-round bout, but was disqualified for supposedly leaving the ring after the cornermen of both fighters entered the ring and exchanged blows, followed by several others.

“Morrissey, when next seen, was on his knees, waiting for his seconds to lift him up,” wrote The Herald reporter who’d witnessed the affair. “The ring was then filled by outsiders, and before they were put out, the referee decided that Morrison had won the fight. This unlooked-for-decision took everybody by surprise, but the fiat had gone forth, and Morrissey was taken out of the ring; Sullivan remained in the ring, calling Morrissey to continue the battle.”

In voicing his protest over the decision, the reporter then made disparaging remarks about the skills of Morrissey in contrast to those of Sullivan, stating: “Morrissey, on the other hand, is a slow man, without much knowledge of ring fighting, and does not see advantages that others more experienced would take, relying more on his great strength and endurance than on science to carry him through. He is a game man but a poor ring fighter.”

Since Morrissey had captured the crown of American bare-knuckle fighting by what could generously be referred to as a technicality, any reasonable person might’ve expected Morrissey to be humble given the dodgy circumstances under which he had ascended to the throne. Instead, Morrissey reportedly made a habit of running his mouth, which caused him to run afoul of local butcher Bill Poole, who was the leader of the Bowery Boys gang.

In the earliest account of the events that transpired before news spread and the story gradually became more sensationalized, multiple New York newspapers reported how Morrissey had claimed that he couldn’t wait to get ahold of Tom Hyer. Not only was Hyer the first recognized bare-knuckle fighting champion in American history, and a man who still had a lineal claim to the title since he’d never lost the title in the ring, but he was also politically-affiliated with the Bowery Boys.

On this particular day, The New York Evening Post reported how Morrissey claimed, “I could lick Tom Hyer or any man,” within earshot of Poole, who assured him that he could do no such thing. After some haggling over the wager of the fight—which was ultimately set at $50—the two men agreed to meet at the Amos Street dock, also known as Pier Six, on Thursday, July 27th at seven a.m.

The $50 wager between Morrissey and Poole wasn’t the only bet placed on the fight, as news of the pending fight between the two men quickly reached local sporting houses, with many of them laying odds on the fight. By the time the two men met at Pier Six for what they agreed would be a “free for all,” which provided them with carte blanche to attack a downed opponent, at least 300 other people had arrived at the Amos Street dock to enjoy the clash in person.

Poole arrived via wagon, while Morrissey walked to the pier with his friends. The two men then stripped off their clothes and began to exchange punches as the crowd gathered around them. From there, the particular of the action were described in The Evening Post as follows: “Morrissey succeeded in planting an ugly blow on Poole’s left eye, which caused a black spot on it. Poole then made a feint at Morrissey, dodged, and by an expert movement caught him around the leg and threw him on the ground. He then jumped on Morrissey and beat him with his fist, cutting his face in a shocking manner. Morrissey at length cried out ‘Enough!’ when his friends interfered and extricated him from his unpleasant position.”

From there, things nearly turned deadly as Morrissey reportedly rose to his feet and screamed, “Give me the pistol!” to his associate Johnny Ling. Before Ling could extract the pistol from his pocket, he was knocked down. A melee ensued, with Poole’s larger gang of friends gaining the upper hand and beating Morrissey’s associates mercilessly.

In the middle of the brawl, someone announced that police had been summoned, causing the brawl’s spectators and participants to flee. Morrissey was lifted onto a carriage and driven away while Poole hopped aboard a small boat and rowed his way down the Hudson River. The event had putatively lasted fewer than five minutes, and in prescient fashion, the recounter of the episode predicted that future violence between the fighters and their factions would follow this skirmish.

Following the initial report of the fight between Morrissey, Poole and their gangs, narratives of the event spread to other parts of the country, with many embellishing the story for the sake of effect. By the time the story reached the newspapers of Pennsylvania, it had been exaggerated to such an extent that Poole had allegedly gouged out both of Morrissey’s eyes and likely left him blind. Morrissey wasn’t blind given events that unfolded just a few months later.

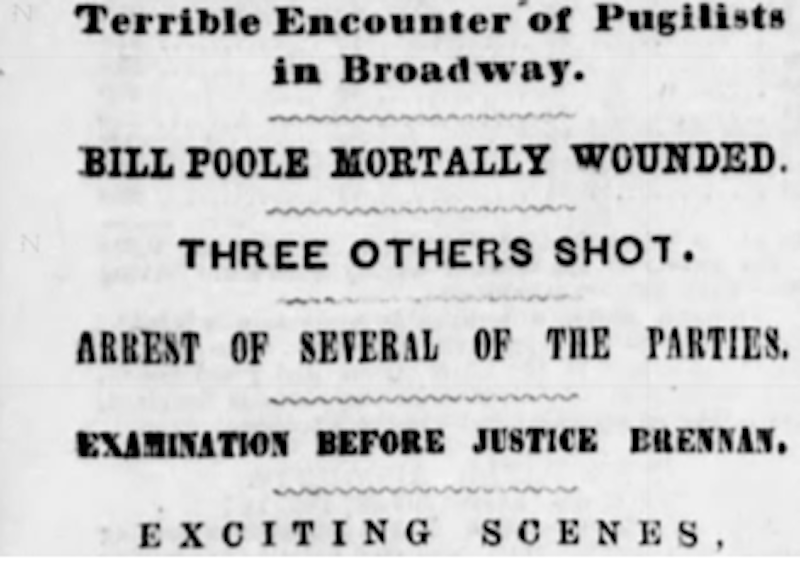

In late-February of 1855, Morrissey and his friends tracked down Poole at the bar of Stanwix Hall on Broadway. Witnesses later testified that the two exchanged insults, with Morrissey accusing Poole of being a “black muzzled son of a bitch” who tried to murder him with the help of friends, and Poole retorted that Morrissey was “a lying Irish son of a bitch.” Pistols were drawn with no shots fired at the time, and both Morrissey and Poole were taken into police custody. However, when Poole returned to Stanwix Hall later in the evening, he was subsequently confronted by friends of Morrissey and shot four times. Poole ultimately died from his wounds while Morrissey and his friends all walked away as free men after their trials resulted in hung juries. It was rumored that Tammany Hall politicians influenced the outcomes of the trials.