The smart mark knows too much and understands nothing. He tracks television ratings the way seagulls follow the trawler. He speaks in a dead language of quarter-hours and demographics, muttering about key demos the way old-timers used to talk about fixing fights. The language sounds important but means nothing now. Never did.

The smart mark sits in his basement, stroking his metaphorical or literal neckbeard and monitoring X for news about which wrestler might jump to which company. He calls them “workers,” like they're still carnies running games at county fairs, or “boys,” like he’s some creepy art director laying out a circa-2002 Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, and laments the “money mark” owners who overpay for their services. Sitting high and mighty in the position of fantasy owner, he pretends to understand the business while missing what business really is.

One of my best friends switched jobs three times in two years. Each time he got a better deal. Nobody called him a traitor. Nobody tracked his moves online or debated his loyalty. He was just a guy doing his job, trying to make more money.

But let a wrestler change companies and the smart marks lose their minds. They treat it like a soldier deserting his post. They forget these are just performers working for their pay, same as my friend, same as all of us.

The funny thing is how seriously they take it all. They analyze wrestling shows like they're going frame by frame through the Zapruder film. They compare viewership numbers to 1996, when wrestling still mattered to people who weren't already watching it. Back then you had to choose between some dumb sitcoms and two wrestling shows on Monday night. Now you've got a million things to watch, most of them better than sweaty men pretending to fight.

These fans remember wrestling the way old men remember baseball before television. Everything was better then, they say. The moves were more realistic. The stories made sense. The champions looked like champions. But memory plays tricks. The past always glows brighter than it should. That golden age ended not long after you first laid eyes on it, after you grew too old and wise to love stupidly and unconditionally anymore.

I watched an old match the other day, one they all talk about. Two legendary performers, supposedly at their peak. They looked slow, clumsy—two middle-aged, bandy-legged men with conspicuous “moobs” in loose, saggy trunks. The moves that once seemed devastating now looked fake. The crowd that sounded like thunder on my childhood TV barely made a ripple through my speakers.

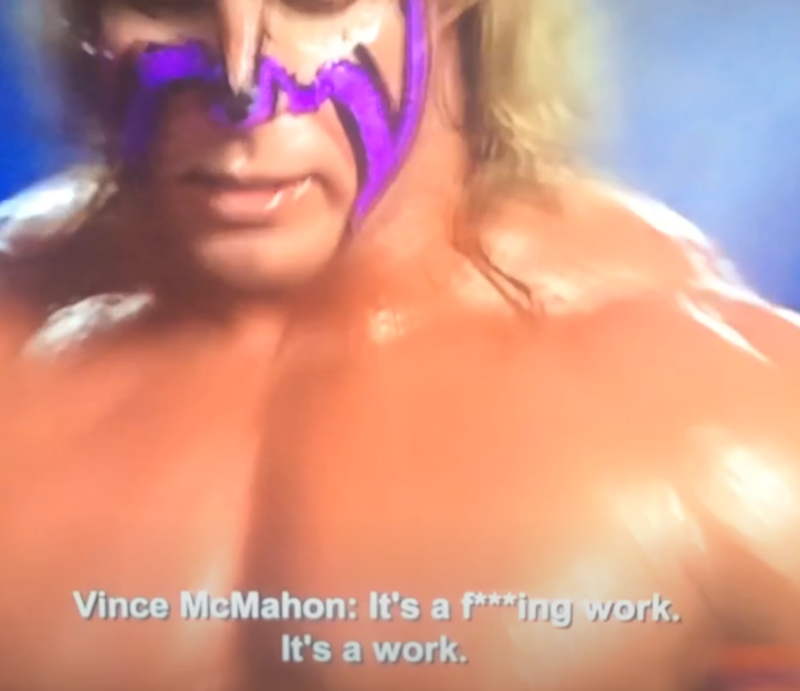

Vince McMahon, who made more money from fake fighting than anyone, once had to explain to one of his biggest stars that none of it was real. "It's a work, Jim," he told the Ultimate Warrior, who was struggling to issue an in-character apology to a fan he’d offended. Warrior wanted to protect his character's dignity. McMahon just wanted to sell tickets.

The smart marks think they're in on the joke. They use faux-insider terms like "kayfabe" and "shoot" and "work yourself into a shoot." They trade gossip about backstage politics like they're covering the machinations of Mossad. They forget that knowing how a magic trick works doesn't make you a magician.

Wrestling still makes money. The media companies need content, and wrestling fills hours cheaply (AEW just got $150 million a year and they don’t even average a million viewers on their flagship program). But it's not 1996 anymore. The cultural moment passed. Now it's just another show, competing with a thousand others for attention.

The real marks aren't the casual fans who cheer the good guys and boo the bad guys. At least those kiddos and Lenny-like adults are having fun. The real marks are the ones who think they're too smart to get worked. They're the ones who follow every contract negotiation, who argue about television ratings, who treat fake fighting like it's the Vietnam War.

They remind me of the old horseplayers at the Meadows who used to brag to my dad that they had a system. They knew the trainers, knew the jockeys, knew which horses were ready to break out. They had all the information except the only piece that mattered: they were going to lose because the house always wins.

Wrestling fans lose too, but differently. They lose time arguing about things that don't matter. They lose perspective pretending that business decisions are personal betrayals. They lose the simple joy of watching a show once intended for small children and child-brained adults by trying to outsmart it.

The truth is simple but they don't want to hear it. Wrestling is a job. Wrestlers are actual workers, albeit ones without insurance or retirement benefits. Wrestling companies are companies. Everything else is just storytelling, and the best stories are the ones we tell ourselves to live.

Sometimes I wonder what these fans do for a living. Do they analyze their coworkers' career moves with the same intensity? Do they track the ratings of other TV shows, like the Big Bang Theory rerun lead-ins that always outperform AEW’s shows? Do they remember what they loved about wrestling before they knew too much?

The smart marks think they see the whole picture, but they're looking through the wrong end of the telescope. They've learned all the secrets except the one that matters: sometimes knowing less lets you enjoy things more.

For all his faults, McMahon was dead right when he told Warrior it was just a work. He might as well have been talking to all of them, all the smart marks who think they know the business because they read about it online. It's still just guys in tights pretending to fight. The real work is believing that any of it matters.