In September of 1982, a masked wrestler purporting to be Mr. Wrestling II appeared in “Cowboy” Bill Watts’ Mid-South promotion—an expansive but undercapitalized territory that produced wrestling shows in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and Oklahoma. “Number Two,” as commentator Watts and the raucous crowds called him, was approaching 50 by this point, yet the guy under this mask appeared significantly more muscular and athletic. “That’s not Johnny Walker,” I thought as my mind drifted into the liminal state between dream and wakefulness. “That looks like Len Denton, the Masked Grappler. Heh, they must be working another masked wrestler mix-up angle.”

Recently, I’ve been watching through the catalog of mid-South TV tapings as a means of falling asleep. I’d done this once before, in the late-1990s, in order to familiarize myself with the history of the sport. I was now doing it as a way to self-soothe, half-observing while familiar personalities such as “Hacksaw” Jim Duggan and “Dr. Death” Steve Williams (both in their rookie years as wrestlers) traded make-believe blows and lulled me into a deep slumber.

But something funny happened on the way to bedtime: I became invested in the handful of storylines playing out in mid-South. Watts has been hailed as a genius booker by others in the industry and by himself in his entertainingly self-aggrandizing autobiography, but I always had my doubts. Booking a wrestling card, it seemed to me, amounted to nothing more than taking some good guys and matching them up against some bad guys. This is what prime-period World Championship Wrestling had done and what the WWE had been doing for the past 30 years.

Watts, however, brought an artfulness to his limited palette of matchup options. The “Cowboy” never had more than 20 or 30 wrestlers on his roster, a far cry from the 100 or more on contract with WWE today, and he needed to keep moving these parts around in order to keep the shine on top stars Ted DiBiase, “Captain Redneck” Dick Murdoch, and the Junkyard Dog.

The mid-South model was pretty simple. DiBiase had recently made a major turn from good guy to bad, displacing Bob Roop and “Mr. Wonderful” Paul Orndorff as the company’s primary heel. Dick Murdoch, who several wrestlers have accused of having actual ties to the KKK, offered red meat to the region’s white trash base by giving them fast-paced matches filled with biting and eye-gouging. And the Junkyard Dog was both the mid-South’s superhero and arguably the most popular African-American wrestler ever, a beard-topped mountain of muscle whose two-minute squash matches and aura of invincibility would’ve convinced most betting men that he, not Hulk Hogan or Ric Flair, would become the sport’s first great crossover star.

Those three wrestlers were permanently stationed at the hub of the wheel on which the mid-South turned, and all of the comings and goings that occurred in the company were routed through them. Jim Wehba, a Lebanese-American wrestler from Texas who competed under the name “Skandor Akbar,” managed a revolving-door stable of monstrous bad guys who were hired as bounty hunters or permanent henchmen and tasked with defeating Murdoch and the Junkyard Dog. Ted DiBiase, meanwhile, operated as an independent bad guy alongside his self-appointed bodyguard Jim Duggan, who’d been recruited from the “special teams suicide squads” of the Atlanta Falcons to protect DiBiase against all comers.

This proved a formula for success, in that it allowed an endless array of well-regarded journeymen to cycle through the promotion take their shots at the top stars. Watts employed many variations on this, such as having wily veteran Jody Hamilton, who wrestled under a hood as the Masked Assassin, make an appearance as ex-NFL star Ernie Ladd’s hired-gun tag team partner, only to double-cross Ladd when Skandor Akbar offered him twice as much money. That particular angle served to turn Ladd, the greatest African-American bad guy of the 1970s, into a reluctant good guy while once again explaining to fans—“educating them,” in wrestling parlance—that the Assassin wore a mask to hide his identity because he was an unscrupulous bounty hunter who’d betray anyone at a moment’s notice.

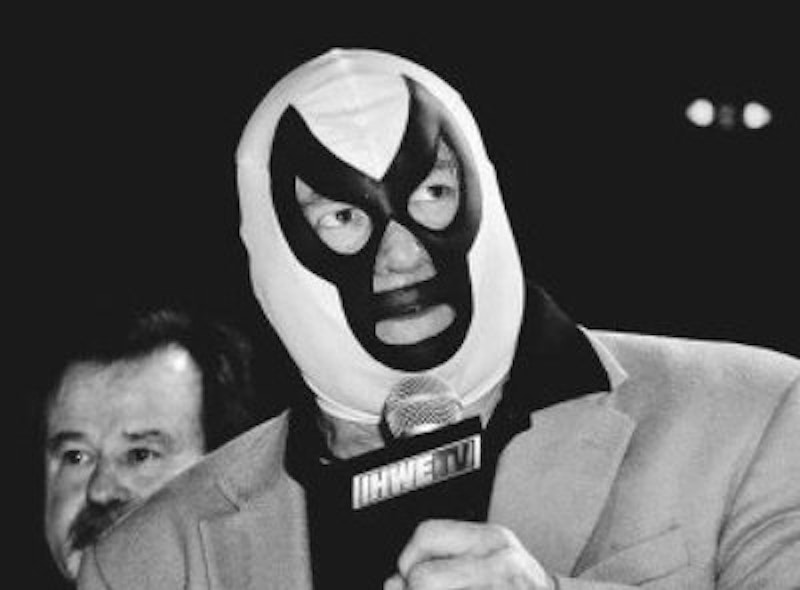

The real Mr. Wrestling II hadn’t yet arrived in the mid-South territory when the fake one showed up, taking down opponents with a similar set of grapples and holds, and finishing them with Number Two’s feared “running kneelift.” I’d watched plenty of Number Two’s work in Georgia Championship Wrestling, where he’d been a mega-star whose celebrity earned him an invite to Jimmy Carter’s presidential inauguration (he politely but publicly declined because it would’ve required him to unmask) and I knew this pretender wasn’t the genuine article. Johnny “Rubberman” Walker, the actual Mr. Wrestling II, was an adept wrestler who could still work a good match in spite of his advanced age, but his white trunks now hung limply on his flat dad-butt like a droopy diaper, and he was never as muscular at any point in his career as Len Denton was in his early 20s.

Denton, who wrestled in mid-South as the Masked Grappler, was a middle-of-the-card bad guy whose job was to beat up on the lesser good guys and lose to the better ones, all in the service of advancing storylines centered around Junkyard Dog and Dick Murdoch. He did this about as well as anyone could, always staging one of the better matches on a given television taping.

Mid-South was unique for the era in that minor and major title changes happened on-air rather than only at live events, an innovation sometimes attributed to Watts but more frequently Buck Robley, one of his veteran wrestlers and an occasional matchmaker/behind-the-scenes figure. This also made sense in such an expansive wrestling territory, where the rotation of shows encompassed many more towns across a much more dispersed geographic area; it gave fans separated by 1000 miles a way to follow the ebb and flow of mid-South action.

Denton had held and lost both of the mid-level mid-South belts, the Mississippi Championship and the North American Championship, so he was usually in the thick of things. And now he was again, this time posing as Mr. Wrestling II so that he could perform as a special and ostensibly unbiased referee in a match featuring one of Skandor Akbar’s minions. Denton was also part of Akbar’s stable of villains and planned to ensure the match went Akbar’s way, but before he could fulfill this role, the real Mr. Wrestling II hit the ring and ousted the ersatz Number Two.

Mr. Wrestling II then cut one of his famous furious promos about the sanctity of his mask, demanding that mid-South owner Bill Watts, who was standing in the ring and holding the microphone, look him in his “fiery blue eyes” and verify that he was the same masked man Watts had wrestled on many prior occasions. Watts conceded he was, and the stage was set for a mask versus mask bout between Number Two and the Grappler.

That match comprised a brisk eight minutes of television time, roughly a quarter of which was devoted to the Grappler trying to remove Mr. Wrestling II’s mask and Number Two frantically selling his desperation at the thought of losing this precious totem. In the end, both masked men skillfully teased running kneelifts—this was an era when it was widely established that certain finishing moves, such as the feared “heart punch,” could only be pulled off by certain wrestlers, and here that was demonstrated by the Grappler rushing in for the coup de grace only to connect with Mr. Wrestling II’s shoulder—until Number Two at last connected square on the Grappler’s chin and pinned him.

The mid-South storylines will progress from here, but this moment in time is beautiful to contemplate. Watts was producing low television but he presented it straight, as serious populist sport featuring competitors with legitimate athletic pedigrees; this is why it’s much easier to re-watch mid-South footage than those sloppy, kick-and-punch Jim Crockett Promotions studio tapings from the same year (notable primarily for the epic Ric Flair, Roddy Piper, and “Boogie Woogie Man” Jimmy Valiant rants that consumed much of each show). There’s a soothing sameness to watching as men like Mr. Wrestling II drifted in and out of mid-South, challenging one regional star or another, while promising lesser lights such as Buddy Landel, Jesse Barr, and Tim Horner honed their craft by losing fast-paced matches early in each show.

We can’t return to this distant grappling past any more than we can, say, let talented hack writer Peter David spin out his Incredible Hulk narrative across hundreds of comic books. It happened, it was something that was, we saw it or read it. And for as long as such media remains stored somewhere, it awaits our rediscovery, providing the same thrills at the same pace it once did. It may mostly mean nothing to nobody, but that’s the case for almost everything, even those three or four inescapable social media topics about which you’re always surprised to discover your older relatives and very young siblings know zippo. The mental landscapes we choose to inhabit are vast but lonely, so very lonely.