Owing to an @Schwarzenegger tweet that had been retweeted by a friend of mine, I learned that I could stream muscle-publishing magnate Joe "The Master Blaster" Weider's memorial online. There was even a minute-by-minute countdown until that blessed event, although I wasn’t able to hold my breath in anticipation as long as the late “Master Blaster” Weider could. Weider lived an almost impossibly extended life— 93 years, two decades more than the “threescore years and ten” promised in the Old Testament. By the time he died in 2013, he’d long since passed into legendary status, with his name (pronounced "Wee-der," not "Why-der," although I favored the latter version until a few years ago) plastered across nearly every piece of third-rate exercise equipment ever sold at your friendly neighborhood K-Mart.

This isn't going to be another matter-of-fact summary of the Master Blaster's bona fides. The story of Joe Weider's rise from first-generation Jewish immigrant anonymity in Montreal to exercise mogul-dom has been documented extensively elsewhere, most notably in the Weider brothers' autobiography Brothers of Iron, which is filled with the sort of selective memories and self-aggrandizing anecdotes you'd expect in such a source, as well as in Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors, Randy Roach's sprawling self-published weightlifting history. Instead, I'd like to address Weider's invaluable contribution to the late 20th-century problematization of the male body.

Growing up, I harbored an intense desire to reach epic, Ted Arcidi-esque powerlifter proportions. This was a ludicrous and implausible objective, but it arose out of painful experience: by cultivating such a carapace of hard muscle, I hoped to armor myself against the depredations of my father, a former star college athlete who bulked large in my life for a very long time. This concept of muscularity-as-armor has been written about to great effect by feminist academic Susan Bordo and literary critic Samuel Fussell. For my purposes here, it’s sufficient to note that this desire brought me into contact with the manifold and variegated works of Joe Weider.

For the young, aimless meathead in the early-90s, Weider was unavoidable. He was the "trainer of champions,” meaning champions of beauty pageants that he sponsored and judged. He was the "father of bodybuilding,” by which one means the person who popularized and, I’d later learn, degraded an activity that actually had its roots in late-19th century gymnastics and strongman competitions. He was the "king of supplements,” most of which probably consisted of little more than flour and baking soda. My first set of weightlifting gloves bore his name, although I had, as mentioned previously, no idea how to pronounce it (also, no one anywhere should ever, everuse weightlifting gloves for any reason besides looking cool in a co-starring role opposite the Rock). Some of the first and most worthless fitness advice that I received came from his horrifying glossy magazines. I purchased a set of rinky-dink Weider dumbbells, which I kept under my bed and used to perform the hundreds of bicep curls recommended in the aforementioned glossy magazines.

I did all of this, contributing tiny amounts of my allowance to the Weider coffers, without realizing the Master Blaster's pernicious influence on the American male writ large. As I continued my fruitless quest to construct a body so big that it would be heard long before it was ever seen, I looked past the freakish performance-enhancing drug creations that festooned the nigh-pornographic pages of Flex. The only other male body that I cared about—really, the only body I cared about at all during this period—was my father's immense frame. Not until years later, after I’d long since abandoned my quest for superhuman size and begun focusing on general fitness, would I recognize the ramifications of Weider's lifelong effort to enrich himself at the expense of others.

Like fellow charlatan/businessman/con artist Vince McMahon, Weider conquered a disorganized niche sport. Arising in opposition to 1930s-era physical culture enthusiasts like York Barbell magnate Bob Hoffman and diminutive Sealtest muscleman Dan Lurie, the Weider brothers wrested control of the physique competitions that these fitness pioneers oversaw. Hoffman, who supervised the US Olympic weightlifting program during the most successful period in its history, staged his AAU "Mr. America" muscle pageants as add-ons to strength shows and lifting competitions. However, the popularity of these exhibitions exceeded that of the events preceding them, and, regardless of whether the pageants were held first or last, they invariably drew larger crowds than the athletic components of Hoffman's AAU meets.

The Weiders, operating across the border in Canada, quickly recognized the potential inherent in such bodybuilding spectacles. Even as Bob Hoffman and his supporters argued that one should "train for strength and form will follow," Weider used his magazine Muscle Powe rto argue against the 3-day-a-week, 3-lift, 5-set-by-5 rep routines favored by massive brutes like 300-pound powerlifting champion Paul Anderson:

“Let me tell you fellows, you'll never become a [bodybuilding] champ with 3 workouts a week. So, as far as I am concerned, none of them [Hoffman, Paul Anderson, et al.] knew what they were talking about. And those who advocate the same methods today are still back in the stone age of bodybuilding. Right now, I am going to bury this stone age idea, this unscientific nonsense, the stick in the mud teachers of our sport have been propounding. I've killed off more stupid bodybuilding ideas in the past few years than all the other instructors put together. Now I am going to debunk another. No champion, not a single Mr. America title winner, ever built his body working 3 times weekly.”

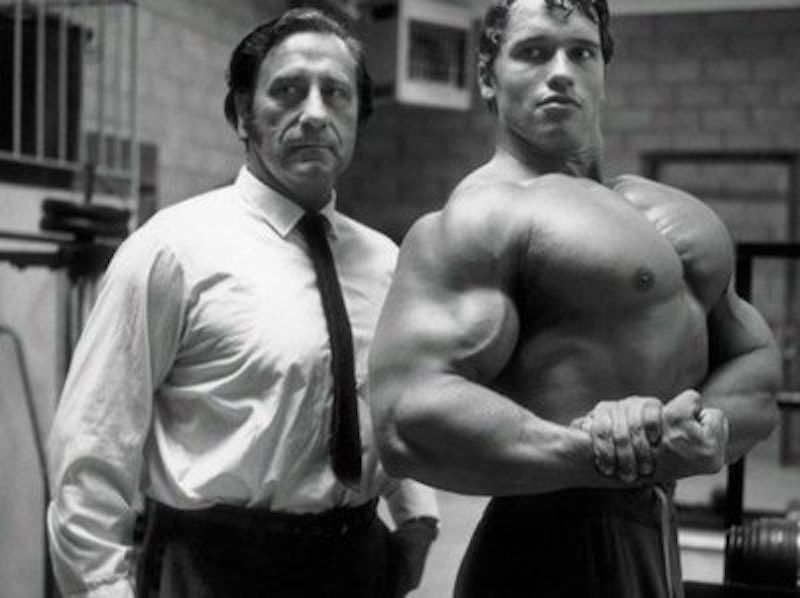

The apotheosis of the Weider routine can be seen in Arnold Schwarzenegger's ambitious but flawed Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding: a rep-heavy, hours-long grind that is undoubtedly intended to be done in conjunction with a regimen of anabolic steroids of the sort that physician John Ziegler introduced into professional sports in the late-1950s. There are merits to Weider's method, and Weider himself, although never a good lifter in any conventional sense, employed it to good effect in the course of developing a lithe, sinewy body that enabled him to place competitively in a handful of 1950s muscle pageants.

But, as is the case with the ill-trained but slick-talking sports guru Greg "Coach" Glassman and his periodization-free CrossFit methodology, much of what Weider endorsed in official organs like Muscle Power was bullshit. Safer, more performance-oriented approaches to weightlifting, like those outlined by former powerlifters Mark Rippetoe and Jim Wendler, are in the tradition of Hoffman, Anderson, and shoulder press champion Bill Starr; they owe almost nothing to Weider's work.

But this is altogether too much history, and very nearly beside the point. What matters for our purposes is that Weider's mantra of "train for form and strength will follow" would eventually win the day; he triumphed by separating the physique pageants from the athletic moorings that had grounded them in performative reality, and then took his act mainstream when Ziegler's first-generation steroids came into widespread circulation during the 1960s, changing forever the look and shape of the pageant "champions" (i.e., the men that Weider picked to win, in the same way that Vince McMahon picked his John Cenas and Hulk Hogans to wear the title belts) that Weider bragged about "training" (i.e., remaining indifferent to their use of anabolic drugs). Whence we have had forced upon us, in turn, Reg Park, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Lee Haney, Ronnie Coleman, Jay Cutler, and now the shameless Kai Greene.

Was Joe Weider, who inspired a generation of young men to build these first-class physiques, really such a bad guy? A full answer to that requires a brief discussion of how the Master Blaster paid the bills back in the late-1950s, when the federal government still aggressively prosecuted the sale of pornographic material through the postal mail and full frontal nudity was banned. During this period, magazines like the pocket-sized Tomorrow's Man, published and edited by the homosexual nutritionist and fitness expert Irvin Johnson, began doing gangbusters business among male readers.

Tomorrow's Man featured the work of some of the finest gay physique photographers of the time, men like Earle Forbes and Lon Hannigan, as well as articles on diet and nutrition from Johnson, who claimed to have invented the earliest protein supplements. For Johnson, the magazine was a labor of love; for Weider, who was neither gay nor at base particularly interested in nutrition or even fitness, its audience represented yet another market to be exploited. In short order, Weider was ripping off Tomorrow's Man and muscle enthusiast Bob Mizer's all-illustration, no-content Physique Pictorial with trashy, exploitative, and extremely lucrative offerings such as Demi-Gods and The Young Physique. In an extraordinarily homophobic article published in a 1957 issue of Bob Hoffman's exercise-oriented Strength and Health, York Barbell weightlifter Harry Paschall excoriated all of these publications but singled out Weider's offerings as particularly worthy of scorn:

“We agree...that the Weider publication Demi-Gods (along with its sister magazine The Young Physique) sets a new low in the sordid world of the queer books. The menace of these homosexual magazines is more serious than ever before, and the cause of clean physical culture threatened by peddlers of pornography.”

As David Chapman and Brett Josef Grubisic explained in their excellent pictorial history American Hunks: The Muscular Male Body in Popular Culture, not all of this material was created equal—and Weider's publications were of a far lower standard of workmanship than those of his competitors, most likely because he was only in it for the money. By the time the feds moved against his offerings, Weider had already departed for the bigger time: peddling the tanned, greased-up, and extraordinarily "camp" heterosexually-presenting monstrosities who’d owe their fortunes to his patronage.

Here, then, is where Joe Weider worked his worst mischief. He, like Vince McMahon, seized control of an admittedly silly but strangely profitable little industry that was ripe for the plucking. To accomplish this, he first commodified the male body. But in so commodifying it, he alienated the male body from any conceivable function that it could perform. He took the male body away from the homosexual photographers who had, from the time of Eugen Sandow's arrival on American shores at the turn of the century, succeeded at glorifying it in heretofore unimaginable ways. Instead of beauty, Weider offered them cheap filth, the sort of material that, taken to its logical conclusion, culminates in the truly depressing (e.g., google “Kai Greene grapefruit”). To the weightlifters in Bob Hoffman's York Barbell camp, the men who won gold medal after gold medal at world lifting championships, he replaced their actual strength with the mere illusion of strength ("train for form and strength will follow!"). And for the rest of the men who in one way or another reacted to bodybuilding culture, he gave them an aspirational image, beamed out along supermarket checkout aisles throughout the land, to which no reasonable person, male or female, should ever want to aspire.

Then he sold those aspirants a bunch of junky products and flour pills that he claimed would replicate the effects produced by chemical substances developed via legitimate scientific research. He assured them, in a manner redolent of Charles Atlas' old "The Insult that Made a Man Out of Mac" advertisements, that other men would submit to their newfound muscles and women would swoon over them—insofar as women were involved in any of this muscle-building business at all. As noted in The Power and the Gory, Paul Solotaroff's account of the steroid-fueled rise of 1970s bodybuilding icon Steve Michalik, women were frequently cast aside in favor of an extra hour or two to lavish on "back day.” Then he up and died at age 93, wealthy beyond my wildest imaginings, and a livestreamed funeral and this body image quagmire amounted to the legacy he left us.