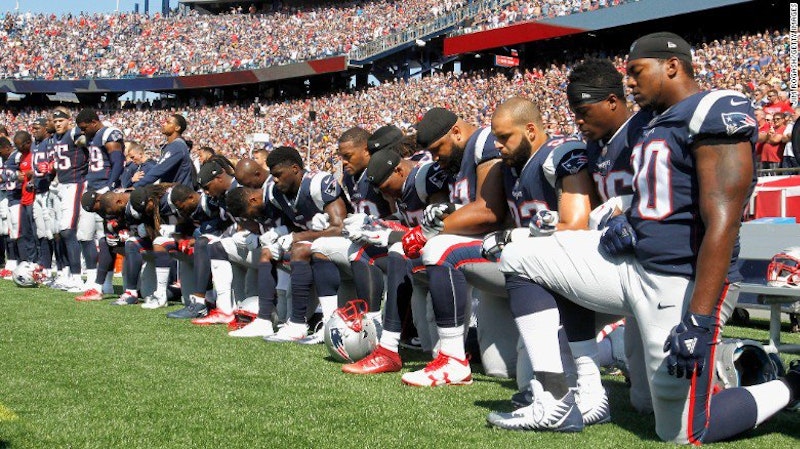

The NFL has decreed that its players can no longer kneel to protest police brutality during the national anthem. Teams whose players kneel will be fined. Players who do not want to stand will be allowed to stay in the locker room—which of course negates the purpose of public protest.

Most of us aren't NFL players. But the dynamic is familiar to just about anyone who’s held a job. When you're at work, your conscience is not your own. Your boss says what you're allowed to care about and how to express your opinions. Your employer tells you where you're allowed to be, and what you're allowed to do with your body.

Americans boast about living in a country of freedom and liberty. But we spend more hours at work than people in any other industrialized nation. And while we're at work—for the majority of our waking hours—we’re under the command of someone who tells us where to be, what tasks to perform, how to behave, and what to think about. The day-to-day experience of the vast majority of Americans is one of subservience, under pain of financial ruin.

Sometimes workplace oppression is obvious—and at least borderline illegal. Elon Musk's factory workers have to work long hours even when injured; many have collapsed on the floor and had to be taken away in ambulances. People who worked with actor Jeffrey Tambor were expected to put up with his screaming rages and verbal abuse. Women who worked at Massage Envy were expected to tolerate sexual abuse and harassment as part of their jobs.

But freedom at work is circumscribed in smaller, less vivid ways as well. In one of my jobs some years back, working on a high school curriculum, a colleague was directed to remove a reference to the persecution of gay and lesbian people from a history textbook discussion of the Holocaust. She wept, but had no recourse, because at work the boss decides if you're allowed to have principles. I work as a freelancer now; bosses are more distant and work seems more flexible and free. But still, I've had editors speak to me insultingly, in ways I wouldn't tolerate if they weren't paying my bills.

We see employment as an exchange of services for money—a straightforward, free transaction. But employers don't just pay for services. They pay for freedom. The boss purchases the right to tell you where to go, what to do, and not infrequently the right to insult you, regulate your political activities, threaten your health, and verbally, physically, or sexually abuse you.

"Between the employee and the slave, there is no hard analytical distinction," Matt Stahl writes in his discussion of the music industry, Unfree Masters. Slavery’s not the opposite of having a job. Instead, it's an extreme example of the erosion of rights that exists under conditions of capitalist employment.

The continuity between slavery and wage slavery was used before the Civil War, and still is, as a way to excuse the plantation system. The fact that enslaved people were not always worse off than people laboring in factories for pennies was supposed to mean that enslaving people wasn't so bad.

But the lesson is the opposite one. If there are similarities between enslaved people and employed people, that doesn't mean slavery is fine. It means that employment is fundamentally corrupt. Employment as an institution gives someone else the right to prevent you from protesting against injustice. It gives someone else the right to insult and demean you. How is this consistent with freedom?

Many people who fancy themselves defenders of freedom will balk at this description of employment. Libertarians, in particular, insist that freedom can only be found with the "free" market. As long as you freely enter into an employment relationship, they argue, you must be receiving the benefits of liberty.

When you've lived your whole life in a cage, you stop seeing the bars. People believe we can't get along without bosses. It's unrealistic to dream of a life spent following your own conscience rather than someone else's. It's insane to think that there's something wrong with spending all day, every day, obeying someone else. The freest world we're allowed to imagine is one in which you’re not even allowed to kneel.