If sports and games can’t save us from the worse devils of our nature, some whinging Bob Costas-style sportswriter once asked, what purpose do these pastimes serve? As a sports historian, I've wasted a lot of precious time grappling with this seemingly inane question—time that could’ve been better spent absolutely killing it at Super Smash Brothers. While I don't have a definitive answer, I have the germ of one.

Within the discipline of history, there's an irresolvable debate about whether historians should emphasize change or continuity when discussing the past. Unlike the question of whether the US History survey taught to college freshmen should be split at 1900 CE instead of 1860 or 1865, this is a conversation worth having. If one chooses to emphasize change, he or she risks exaggerating the "pastness of the past." In other words, the gunslingers of Deadwood and the immigrant workers who participated in Pittsburgh's "Hunky Strike" become the occupants of an alien land, their weltanschauungen inaccessible even through careful analysis and sympathetic readings of whatever primary sources they've left behind. Taken to its illogical extreme, the writing of history itself is made impossible—how could anyone truly tell the "story" of such an incommensurable past?

We recognize that this is unsatisfactory; the past, as Walter Benjamin observed, continuously piles up behind us as we are blown forward into an eternal present. It stands to reason that certain continuities warrant our attention: hasn't humankind always loved, laughed, hated, warred, ached, wake-and-baked, etc. in much the same way? Doesn’t Fernand Braudel’s longue durée deserve more of our time than breathless recapitulations of a handful of well-known but ultimately insignificant historical events? This approach has its flaws, given that our mentalities are altered over time as new concepts emerge to reshape our discourse. That isn't to say that a figure from the past, magically brought forward into the future by the machinations of some Doc Brown-style mad scientist, couldn't eventually translate his thoughts into our language, but situating this out-of-time individual within a new paradigm would take some doing.

At the risk of wandering too far afield, let me conclude this aside by stating that, while I find the debate fascinating, I have no horse in the race. However, I’ve devoted a lot of attention to popular culture generally and sports specifically because I believe that these subjects can serve as a lens through which we might better perceive what people in the past were thinking about. Consider how much time you spend talking with your friends about sports, television, fashion or some other silliness. If you add it up, it probably amounts to a significant portion of your waking life. If one of my successors seeks to give their audience a window into your thoughts, they’d ignore the likes of Paige VanZant, Antonio “AB” Brown, and John Cena at their peril. Sports aren’t intrinsically important, but derive their considerable importance from the fact that so many people in a given society pay attention to them.

•••

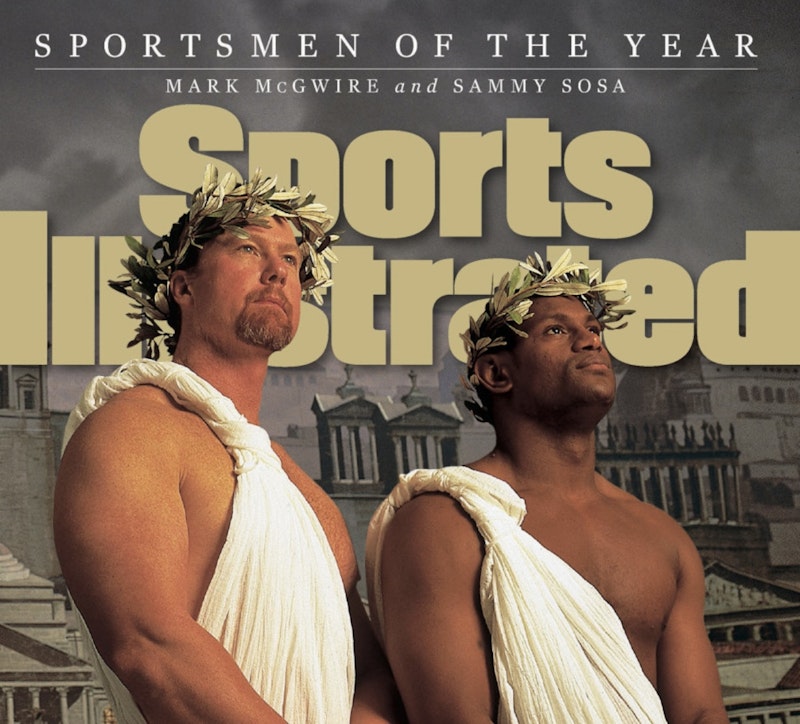

The 1998 Major League Baseball season was one such moment when national attention fixated on professional athletics. Enamored of the back-and-forth home run derby between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, fanboy sportswriters of the “kept a Mickey Mantle baseball card fasted to my bicycle wheel” variety waxed poetic about how these twin demigods had redeemed a game still recovering from the devastation wrought by the cancellation of the 1994 World Series.

When these two unfortunates were exposed, along with countless others, as PED users, the reprisals were swift and brutal. Now we got the other story that sportswriters will never tire of writing: Can sports be saved? The public continued to watch professional baseball—the sport is now more profitable than ever, on account of the bizarro-world economics of streaming television—albeit with a sort of weary-yet-aggrieved belief that the men they watched were all dirty rotten cheaters.

In this case, we have a clear example of how a sportswriter-imposed and fantastical narrative can obscure the actual historical value of sports. The trees in our example consist of all this nonsense about who was "cheating" and who wasn't; the forest is the much larger issue of how highly skilled laborers in an extremely specialized industry were modifying their bodies in order to extend their working lives. This is, I believe, one of the signal questions of our current century: what counts, in baseball or in any other endeavor, as performance-enhancing? Even in 2023, we don’t possess a sophisticated enough vocabulary to discuss certain large-scale changes to what constitutes natural human performance—and that realization, even absent any concrete answer to the aforementioned question, is one of enormous significance.

There was nothing special about McGwire's 70 home runs or Sosa's 66 beyond the fact that these were high single-season totals. Neither man was a hero; neither, upon being outed as a steroid creation, became a villain. They were, however, two men among thousands who responded to a host of incentives—some economic, some narcissistic—by electing to take drugs to enhance their play and physiques. With millions of Americans enhancing their own performances using substances ranging from Adderall to Zoloft, McGwire and Sosa are likely worth remembering primarily for how they foreshadowed a major societal shift; in this case, a shift toward better living through chemistry.

•••

Here, then, is my own contribution to the "can sports save us?"/”can sports be saved?” genre. The answer is a resounding no, because both questions are flawed. Whether we are participating or watching, sports can’t save us from a gosh-darned thing, nor can we save glorified children’s games that aren’t imperiled. However, if we reflect carefully on what we’d otherwise perform or consume in a mindless and haphazard manner, we may learn something about who we were and who we are in the process of becoming.