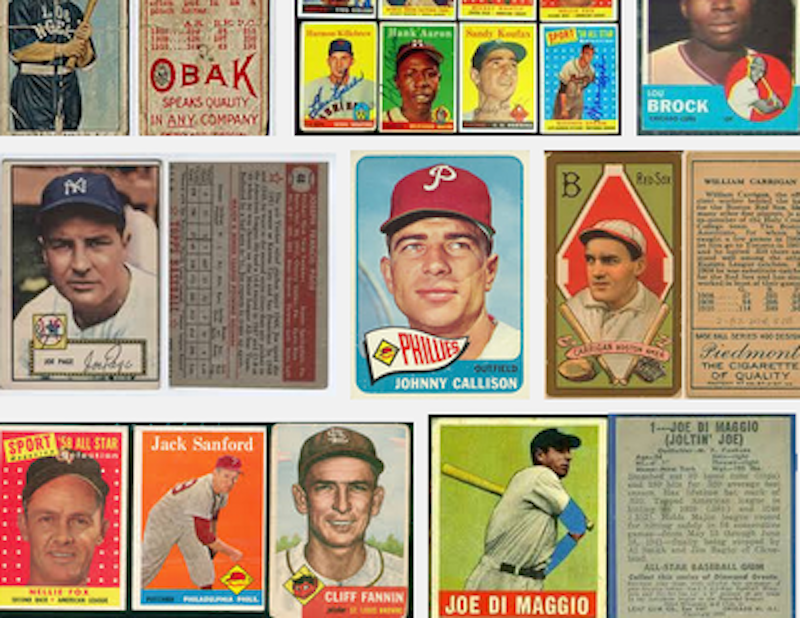

One small contribution to the world of knowledge, or the possibility of the existence of knowledge, is the statistic. We’re interested in one category of the statistic in particular: baseball statistics. Baseball, more than any other sport, has drawn mathematical minds into its orbit for generations. Over the first half of the 20th century, baseball card backs included a brief biography as well as a player’s height, weight, and place of birth. In 1952, Topps, the biggest name in baseball cards, began to print statistics on the backs of their cards. An entire generation began obsessing about baseball statistics in ways their fathers could hardly imagine.

Baseball box scores and cards were ever-present in my childhood. My older brother memorized lineups from The Boston Globe sports section. We played Earl Weaver baseball on an ancient Mac computer in the basement of our friend’s house. Trades were discussed. The younger brothers were often manipulated into making insane trades. Seasons were simulated. I remember seeing the tiny print on the backs of the cards of aging veterans.

Knuckleballer Charlie Hough pitched from 1970–1991. You could spend 20 minutes with all those numbers, and they explain some of Hough’s remarkable career. Starting at the top, we find out he was born in Honolulu in 1949. Continuing on, we see that his first three years in the majors were almost non-existent. We can see that he was a reliever until 1979. Did he develop the knuckleball around that time? For those of us who are sabermetrically-inclined, the lack of strikeouts and enormous number of walks is kryptonite. Hough would be fantasy kryptonite. On the other hand, the man was a knuckleballer! From the Niekros to Wakefield to Dickey, controlling a knuckleball might be the only thing in the sport more difficult than actually hitting the ball. Other stats that stand out: double digits in complete games for six out of seven seasons in the 1980s. In his 1987 season, Hough started 40 games and threw 285 innings!

In an era of Tommy John surgeries and pitch counts, Hough’s numbers look crazy. Even from the vertical position below, the back of his 1991 Topps card shows a career that spanned the musical eras of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” to C+C Music Factory.

As the decades passed, historical records became ever more mythical and provided fodder for fans. Babe Ruth’s home run record, held for 39 years, was broken in April 1974. Thirty-three years later, the symbol of steroid controversy, Barry Bonds broke Aaron’s record. Today, after a decade of scandal, debate, and endless speculation, home run records are all filled with asterisks. In 2014, Topps added the sabermetric stat WAR (wins above replacement) to the back of the card. This marks a sea change for the older generation of fans and a small victory for the younger, saber-loving sorts. As big data furthers our collective desire for quantitative analysis and “truth through numerical analysis” becomes the status quo, it’s no surprise that baseball and basketball statistics and analysis is changing as well.

Consider that the asterisk is meant to designate an aberration, or an exception. Then consider that much of baseball’s early history was filled with asterisks that were never noted. The spitballers of the 1910s, 1920s and a handful of pitchers in the 1930s are just one example. The now-illegal pitch was so entrenched in the game that 17 major league pitchers were allowed to keep throwing the saliva-soaked ball after the pitch was banned in 1920.

We could go on a sabermetric tangent here. The last 20 years has seen Bill James go from authorial eccentric and baseball historian to baseball authority. Fantasy baseball has propelled the statistical focus to new levels. Michael Lewis’ Moneyball provided a spotlight on the value of the walk and how scouting was no longer simply an old boys network of eye-test examiners, but number-crunchers as well. In light of the changes, fans are even beginning to recognize the value of defensive performance and baserunning, as well as the relative importance of pitch count and fielding independent statistics (strikeouts, walks, home runs allowed). The basic knowledge that each ballpark plays differently has been part of the game and scouting for decades. Giving it a term “Park Factor” and evidence of how each park impacts a pitcher, or say, a left-handed batter enables new layers of information that many fans may find irrelevant, but fantasy baseball hounds will dig into. These new ideas, call them “truths” if you like, give us a sense of deeper knowledge about the game. Numbers allow us to gain a sense of objectivity, even if they can be twisted and debated.

In truth, the existence of truth has always been greatly exaggerated. Mythology is ingrained in baseball more than any other sport. The literary fascination with baseball propelled it. Images of baseball in film (The Natural, Field of Dreams, Bull Durham, Major League) furthered the myth-making. The pastoral nature of the game and the now-debated leisurely pace contributed to the distinctive flavor over the decades. The sportswriters and radio voices of the mid-century added layers of color and depth that turned the still images of the game into impressionistic experiences.

Today, baseball is an anachronism. The absence of a clock. The four-hour games. The 162-game season. The unspoken baseball codes of yesteryear are facing constant threats. Instant replay was deemed absolutely necessary and then faces instant criticism. Yasiel Puig’s bat flips become the topic of the day. Should pitchers still throw at opposing batters in retaliation for admiring their home runs or slow-trotting around the bases? What if pitchers throw at batters’ heads? Just 10 years ago, Pedro Martinez and Roger Clemens were throwing purpose pitches near the chins of opposing batters. It’s safe to presume that they would never be allowed to get away with their intimidation tactics today. Hitters wearing military-grade elbow pads lunge over the inside corner. After a century of getting battered by foul balls and nasty collisions at home plate, catchers are now protected, but the new rule regarding catcher obstruction of the plate and instant replay amp up the catcher controversy. Baseball’s declining popularity has been greatly exaggerated, just as its designation as the “national pastime” was once embellished. In truth, there are more diversions than ever before, and a slow-paced sport that plays games six times a week for six months—before we even get to the postseason—is bound to become less popular within the realm of popular culture.

Baseball will always provide what you want it to: a great place to spend a summer evening; a perfect complement to a walk or a car ride; a physical game that involves lush grass and smooth brown dirt; an excuse to drink beer and eat sausages and hot dogs; a strategic game in which to compete obsessively through the Internet; a way of reconnecting with old friends; a slow-moving television experience with too many pitching changes; a wonderfully dramatic city-unifying playoff chase; a crowded never-ending line of people. It’s just a game. But it’s also a way of life.

We don’t watch the games like we used to. But maybe that’s because we never did.

—Follow Jonah Hall on Twitter: @darkoindex