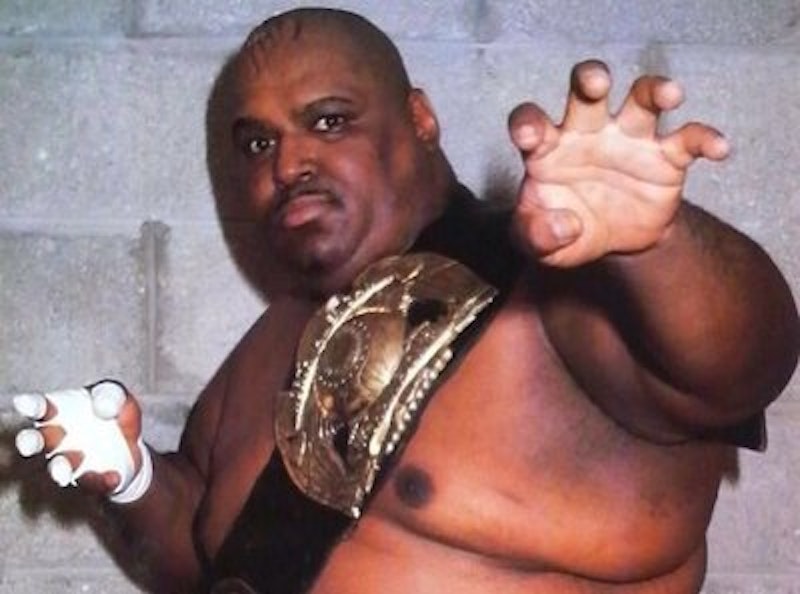

Some might say that gory brawler Abdullah the Butcher was a "real man.” Some might also say that the Butcher was a madman. Graeme Wood opted for the latter in a 2012 profile of Abdullah that appeared in The Atlantic. What I’d say, following the work of sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant, is that the artist formerly known as Lawrence Shreve is a particularly shrewd entrepreneur in bodily capital. Of this Wacquant wrote, “The fighter's body is simultaneously his means of production, the raw materials he and his handlers (trainer and manager) have to work with and on, and, for a good part, the somatized product of his past training and extant mode of living.”

Abdullah the Butcher's body, scarified from a lifetime of self-inflicted wounds, was the canvas on which he produced art for the masses a la the late, lamented "painter of the light" Thomas Kinkade. Over five decades of simulated violence, the Butcher mastered a technique known alternately as "gigging,” “blading,” or "getting color". His only equals in this regard were Dusty "The American Dream" Rhodes, “King” Curtis Iaukea, and Ed "The Sheik" Farhat—three men whose foreheads, like Abdullah's, eventually became masses of puffy, purplish scar tissue capable of bleeding at the slightest pinprick.

Abdullah the Butcher was originally conceived of as a run-of-the-mill phony exotic, another "Madman from the Sudan" portrayed by a heavyset former judo athlete from Canada. But the Butcher, by virtue of his enthusiastic self-butchery, came to transcend his character in the way Ed Farhat transcended his own textbook "evil Muslim" gimmick. At a certain point, what these guys did, which was nothing more and nothing less than immediate and gruesome bloodletting, overshadowed anything else about them.

The Butcher waddled to the ring with fork in hand (or, more likely, tucked somewhere inside his capacious parachute pants), ascended the ring steps, and proceeded to "gig" himself as soon as possible. There was a demand for this unsavory work, particularly among realism-obsessed "strong style" fans in Japan.

Graeme Wood's profile of Abdullah the Butcher went to great lengths to depict Lawrence Shreve as a hepatitis C-afflicted lunatic, failing to mention that, in spite of his many critics, other notable grapplers such as Dick "The Destroyer" Beyer, Barry Windham, and "Bruiser" Brody (Frank Goodish) had regarded the Butcher as a competent, if limited, ring partner. Wood did little beyond discussing the fine points of "gigging" with the Butcher and thereafter purchasing the demonstration fork for $10, whereupon he concluded "that was enough" and departs. That was enough, I suppose, for his story, the principal thrust of which was something along the lines of "can this disease-infected monster really be acting?" By ending so abruptly, Wood left more on his plate than ribs. He left open significant questions about masculinity, capitalism, and the routinization of performative violence. It’s to these questions that I now turn.

I’d read about Abdullah the Butcher in the pages of the various kayfabe-maintaining Apter magazines, Inside Wrestling and its ilk, long before I ever saw him during his brief stint in WCW during the early 1990s or running wild on bootleg VHS tapes of Japanese wrestling. By that point, the Butcher wasn't playing so much an ethnic stereotype as a deranged man, partnered up as the weaker-working half of a tag team with Cactus Jack.

Even in this limited role, Abdullah the Butcher had an astonishing presence. I wasn't necessarily captivated by him, since he was a dismal wrestler and even then my preferences, like those of friends on the wrestling discussion boards, ran toward "workrate" superstars who could perform well-executed grappling for 20 minutes an outing. Nevertheless, the massive body of Abdullah the Butcher, once seen, couldn't be unseen.

"The body," wrote sports sociologist John Hargreaves, "constitutes a major site of social struggles and it is in the battle for control over the body that types of social relation of particular significance for the way power is constructed—class, gender, age, and race—are to a great extent constructed." It seems that the remarkable body of Abdullah the Butcher was constructed in response to the pressures inherent one of the strangest yet most "manly" of performative spectacles.

Almost since its inception, professional wrestling has been a "work," a way of making money akin to a rigged carnival game. It’s incidentally a morality play in the sense that Roland Barthes and others have claimed, but only in the same way that the basketball game at the carnival with the too-narrow hoop is incidentally an athletic exhibition. There were professional wrestling stars in the United States from the 1870s onward, and many of them spent a portion of their careers faking the outcomes of matches in order to increase the amount of money bet and tickets purchased in subsequent rematches, some of which were possibly "shoots" (i.e., matches without predetermined outcomes).

One of the keys to maintaining the illusion of wrestling's legitimacy was the competitors' demonstration of their masculine bona fides through the act of pretending to injure their opponents in extremely realistic ways. Eventually, this came to mean that these men were smashing each other with chairs and baseball bats, throwing themselves through tables and off the tops of steel cages—damaging themselves, ironically, while pantomiming ferocious assaults on their sparring partners.

Abdullah the Butcher's career, such as it was, amounted to the highest and thus most absurd point in the development of this “hardcore" style of self-injury. Though claiming to have been trained in judo and karate, the Butcher's credibility in the ring had little if anything to do with his athletic ability. He wasn’t an Olympian like Ken Patera or Kurt Angle, nor was he an accomplished fake wrestler in the mold of high-flying "Dynamite Kid" Tom Billington. Instead, he was the literal embodiment of masculinity—a term defined by sociologist R.W. Connell as "simultaneously a place in gender relations, the practices through which men and women engage that place in gender, and the effects of these practices in bodily experience"—as it was implicated in the act of professional wrestling.

In wrestling, the holds and throws were fake but the pain was real; a wrestling match, then, was an exercise in masculinist masochism. The "entrepreneur in bodily capital" operating in this arena was not, like one of the boxers Loïc Wacquant studied, supposed to keep himself safe from harm while simultaneously inflicting severe harm on another. He was, rather, meant to harm himself in as safe a manner as possible, or at least as safe as he possibly could while still generating "heat" (i.e., crowd enthusiasm) and surviving to perform another day. The Butcher, likely realizing that the only way he stood to earn a significant living was by being as "safely unsafe" as humanly possible, wrestled in a style that "Hulk" Hogan, "Superstar" Graham, and others came to view as brutal and grotesque.

In the words of John Hargreaves, who argued that the discourses surrounding the sporting body could not be separated from oppressive ideologies of consumerism and capitalism, such violent sporting practices are part of a "system of expansive discipline and surveillance [that] produces 'normal' persons by making each individual as visible as possible to each other, and by meticulous work on persons' bodies at the instigation of subjects themselves." Thus, to manifest the signs of masculinity necessary to his existence as a professional wrestler, Abdullah the Butcher, rather than "juicing" with steroids in the manner preferred by Hogan and Graham, enthusiastically disciplined his body in a way that allowed him to offer spectators an unparalleled look at the violence and ugliness they craved. There was a saying among old-time wrestling promoters that "matches go red before they go green," and the Butcher grasped this concept like few grapplers before or since.

For a host of culturally constructed reasons, men are attracted in far greater numbers than women to violent and dangerous activities. The pressures of hegemonic masculinity—i.e., the need to conform, or at least respond, to society's dominant paradigm of male behavior—have exacted a substantial toll on many men. "Most of the leading causes of death," writes Michael Kimmel, "are the results of men's behaviors—gendered behaviors that leave men more and vulnerable to certain illnesses and not others. Masculinity is one of the more significant risk factors associated with men's illness."

The Butcher himself, along with hundreds of other wrestlers he may have infected along the way, has Hepatitis C—the consequence of innumerable pitched battles in which blood mingled with blood. In prior decades, the great scourge of matmen was trachoma, an infectious disease that results in a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids and, eventually, blindness. Were these men simply the victims of capitalism—wage slaves to an unfeeling promoter who used and abused them in pursuit of the almighty dollar? Certainly there was a need to make it look believable (a truly old-school, blood-and-guts promoter like "Cowboy" Bill Watts would fire you if you didn't), but was there a need to make it look gory, as Abdullah the Butcher, the Sheik, and some others did?

“He was a filthy, scummy man,” former WWE champion “Superstar” Billy Graham said in a 2015 interview about Abdullah. “He was in there cutting people with that fork, almost decapitating people, a felon committing felony assaults and batteries with no right or justification whatsoever. He told me he did it to keep the heat on him, keep people fired up, and I told him he better hope the guys he cuts don’t die.”

However, the situation is more complicated than Graham, a recovering heavy drug user who has admitted he’s prone to fabrications and delusions of grandeur, likes to think. Immersed in what sociologists Kevin Young and Philip White describe as a "culture of masculinism" that encourages risk taking and discourages thoughtful preventive measures, Abdullah the Butcher seems as much a victim of circumstances as anyone else who might find himself similarly situated.

The same competitive, masculinist forces that nearly killed Eric Kulas, a 350-pound, 17-year-old neophyte wrestler who begged Extreme Championship Wrestling star New Jack to "gig" him only to quickly pass out from loss of blood, also impelled the Butcher to endure innumerable hurts throughout his career. For Abdullah the Butcher, it was undoubtedly not just the prospect of immediate financial reward but also the nexus between aggression and the process of masculinization that led him to undertake a lifetime of hazardous, high-risk practices.

Is it any wonder, at the conclusion of such a long and arduous path, he remains proud of his broken-down body and fictionalized athletic accomplishments? With little beyond a dinner fork and thin skin, the Butcher proved himself the manliest of men, consequences be damned. And all it cost him was a $2.3 million civil settlement to wrestler Devon Nicholson, who claimed Abdullah had raked him with a fork and infected him with hepatitis C.

“You can’t blame Abdullah for that shit,” said semi-retired wrestler Vampiro in a 2017 interview about Nicholson’s lawsuit. “You know wrestling is dirty, it’s filthy, it comes from that carnival background... if you’re a boxer and you’re in there sparring with 300 people a year for 30 years, how can you say which punch caused your brain damage? C’mon man, you take a risk, it’s your body on the line.”

Yes, those risks cost Abdullah millions of dollars and goodness knows what else.