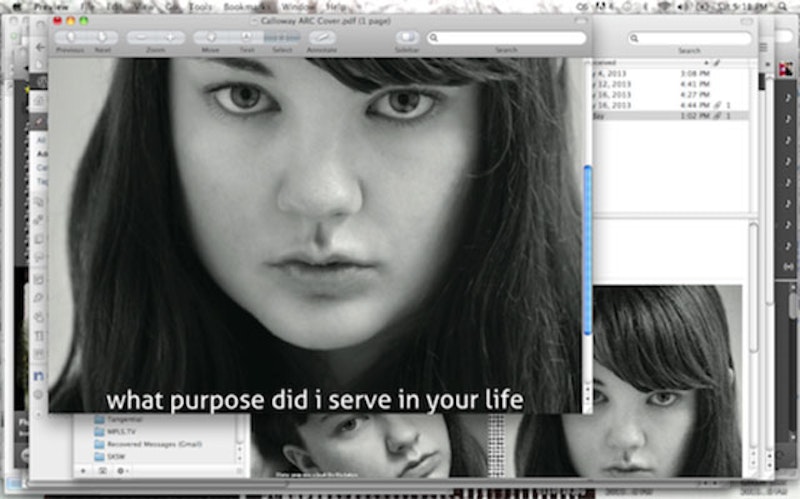

There’s a very small pocket of people under 25 interested in writing that’s of the moment. The realistic audience for Marie Calloway’s what purpose did i serve in your life is absurdly small in proportion to its worth. Through a baker’s dozen of essays using text, photographs, and screenshots, Calloway documents her sexual maturation, from losing her virginity, to her experiences as a sex worker and in BDSM, in a voice that warbles from cool, affected detachment and twisting-the-knife-in-your-gut insight, particularly on how grown men act like babies and want to be nursed until they die.

Plenty of alt-lit is vacant and dull, devoid of anything but affected detachment and poorly edited observations. Calloway’s tone is instantly familiar to anyone who’s young—it turns bratty, cynical (“the station was small and empty and horrible”), crying for attention and at the same time letting no one in, bearing her heart to her readers only in its abridged and edited form. She’s upfront about never needing or having a job, and the freedom that a trust fund affords her. The most striking thing about what purpose did i serve in your life is its insight into the casual emotional abuse of even the most “leftist feminist” beta-males and how impossible it is to see or begin to understand the vulnerability a woman feels every day, even in a comfortable consensual situation.

Calloway frequently calls out her lovers for being hypocritical: act reserved and you’re a prude/not interested, or indulge the slutty side he’s always begging for, only to be laughed at when he feels uncomfortable at his cheesy porno fantasy becoming manifest. In her own words, Calloway seeks out “insecure, pretentious,” semi-wimpy guys, who are classically “nice” but, especially the anonymous subject of “Adrien Brody,” are feckless beyond hope. She effectively eviscerates Brody, who is so timid and scared of losing his “connection” to her if he falls asleep, or clog conversations with apologies, giddy excitement, nervousness, and a resentment of others without so many hang-ups.

Her work here is bold and far beyond what most women her age would admit to, let alone publish in a book. But there is no reason this book should be controversial at all. Of course if it made its way onto The View we might have some problems but to those tuned in to its very existence, well, maybe you’ll find it as moving as I did. Pages away from “Adrien Brody” you’ll find close-up pictures of Calloway’s mouth filled with the subject’s cum, and flattering selfies overlaid with ignorant, sexist criticism of her writing and body. For what it’s worth, she’s beautiful, despite refrains like “I am worried about my face, “I am ugly,” “My legs look fat”—these body neuroses are far too common in women across the board. Calloway’s depiction of the actual sex is unremarkable and intentionally bland. Her sharp observation for the latent, ancient sexism present in even the most shy cute hipster boys is what makes this such a cutting book, speaking as a man. The quote presented at the beginning says it all: “Because of our social circumstances, male and female are really two different cultures and their life experiences are utterly different.” This writing is unsparing and confrontational in its questioning, and this is the way we should be parsing sex today.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992