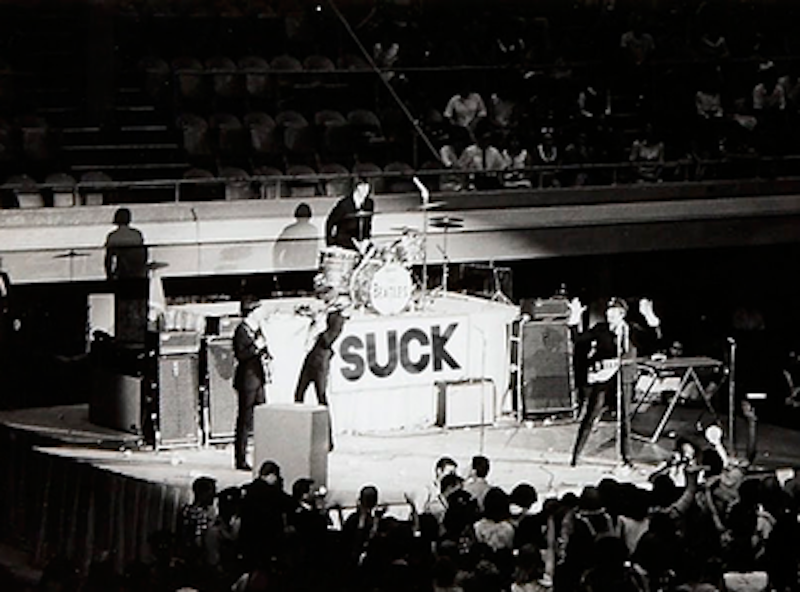

Previous “Why They Suck" posts: David Bowie, Stephen Hawking, Bob Dylan and Picasso.

Many readers exactly like you ask me, "Professor, how did you develop your sixth sense for suck? How is it that you know so infallibly when someone sucks chode?" I often answer that it’s a “gift” I was born with. Like tall, suck divining cannot be coached. And yet I've developed some basic guidelines for the science.

When I was but a wee rock critic, I had the stupendous realization that I'd never write anything interesting if I didn't trust my own taste. By a sheer exercise of Nietzschean will to power, I identified “I like it” with “it rocks,” and “I don't like it,” with “it sucks.” After that, while your opinions remained mere subjective whims, mine took on the ironclad status of eternal Truths.

My hypotheses have consistently been confirmed by data, as neurosuckology has unlocked the mysteries of the human brain itself. It might not have seemed like it, but we had Paul Simon in a scanner as he performed at the Democratic Convention. The big-ass suck region of his brain was lighting up like a like a fireworks show at Katy Perry's house.

Now, plenty of stuff sucks in a loose manner of speaking, but really not worth remarking on. If Bob Dylan was just another half-forgotten 1960s folkie, there'd be little reason to rant. If Picasso was remembered as we remember even Fernand Léger, for example, I wouldn't feel it necessary or decent to spend hundreds of words telling you why he sucks so bad. It would be cruel to his shade and also pretty boring.

But I don't feel this is true for the Beatles or Ludwig Wittgenstein. These people have received such screeching and unanimous adoration for so long that it would take thousands of me working for decades even to make a dent. I don't think people like that can really be significantly insulted: if they feel sad, they can put my shit down and read the reams of scriptures in the cult of themselves. Little human godlings can afford to regard my quibbling with detachment.

Actually, human godlings irritate me. I don't think we have any business worshipping each other, and no human can sustain the reputation of a Michelangelo or a James Joyce or a Beyoncé. Even if their stuff might be admirable work for a human, it’s disappointing when considered as the work of a divinity. We need to keep these folks with us, if necessary by knocking them down a peg. And we need to restrain our impulse to worship one another.

Sometimes, great work stands the test of time. Other times, reputations become so universal and stupefying that mediocrities go echoing down through the centuries like the tolling of great big bells. It becomes impossible even to disagree with the most absurd assessments. We could all use a dose of self-trust. Sometimes you've got to stop nodding along.

Here’s the actual algorithm for “Why They Suck,” the fundamental principle of contemporary suckology. I call it the suck quotient: the ratio of reputation to accomplishment. Accomplishment is fixed objectively in the manner described above. But in a certain way, Picasso has almost got to suck. The work of no human being could pay off on Picasso at the height of the cult: Promethean genius, force of nature, creator and destroyer. No pop act, and certainly not the Beatles, can possibly bear the weight of the Beatles' reputation. Their suck quotient is 99/9 = 11. That really really sucks, but not as bad as Bowie (92/4 = 23). So the people with the most hyperbolic reputations start out at an extreme suck-quotient disadvantage, though not everyone that reaches the top echelon of fame actually does suck that bad.

As you calculate your own personal suck quotient, possibly you can take comfort in the fact that you’re obscure, almost unknown to the public. I have probably never heard of you. Now we may find this neglect of ourselves sad and annoying, and yet, all things being equal, it is helping us to suck a lot less.