The Science of Suckology explained.

Time to kill the boy who lived. Or it would be, but you can’t kill someone who never existed; in this case homicide is impossible and hence excusable. Even outright bigotry is morally insignificant with regard to fictional characters. Fictional characters are inferior to us. They're not real, I tell you. No one’s arguing that fictions should have the vote, or the right to marry real people, if any. They can marry each other, for God's sake; they do it all the time, like Harry marries Hermione. Wait, is that right?

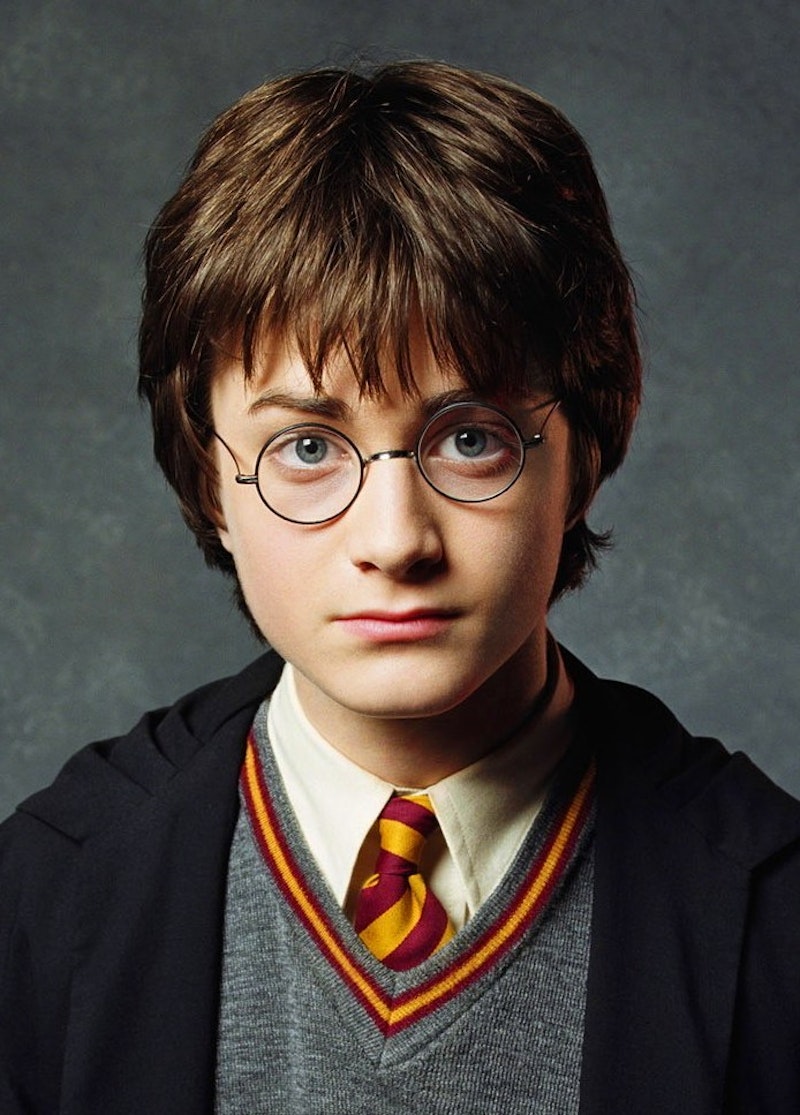

I read the whole massive series aloud to children, three times. It’s very, very long. One thing I will say for the books is that they’re solidly plotted; J.K. Rowling introduces dozens or hundreds of details or clues and somehow makes them connect or work out by the end. There’s also a certain charm in some of the characters, though they started as types, and though everyboy Harry himself remains a kind of bespectacled, bewildered blank even after 35,000 pages. The way kids lust for racing brooms or everyflavour beans sheds light on the way they might have lusted for skateboards and Sour Patch Kids in 2005.

However, there are drawbacks. The worst of these is the failure of what fantasy buffs call “world-construction.” One reason those thousands of pages never settle into any sort of credibility is because Rowling just plops the magic right down in the middle of the ordinary world. People are flying around 1990s-Great Britain on brooms, disappearing from train platforms, living in wizarding compounds and towns, gathering for magic festivals by the thousands, infesting the marble edifice of the Ministry of Magic in London, controlling the weather, and so on. Rowling never makes this make sense and so resorts to ad hoc devices—time travel and memory erasures and force fields—so that people don’t notice anything.

The magic itself is an incoherent hodgepodge: no telling what anyone can and can’t do with all those faux-Latin spells, potions, and charms, or how or why. Any power that any young wizard requires to make the plot come out is likely to be for sale in a shop or hidden in a cave somewhere. The forces that make this possible, or the way the supernatural plane might be connected, or not, to the ordinary world in which the plot occurs: Rowling shows no interest in such matters. All that time, all that reading: I never suspended disbelief for a minute, never imagined any of the people and places as real. My kids did, though, so maybe that’s what counts. Anyway, that’s what kept me slogging on.

As one followed another, each desperately-awaited book became a performance in which Rowling deferred her trademark subterranean roller-coaster climax for as long as possible, grinding through an endless school year of gossip, red herrings, eccentric but useless characters, and whole Quidditch seasons, game by miserable game. Each one, for years, was longer than the last. The moral of it all was something like “It’s good to be good, and bad to be evil.” Characters just seemed to be born one way or the other. There’s nothing of moral complexity or profundity anywhere in these books.

More annoying, as I read myself and my children to sleep, was the quality of the prose. Rowling writes without flair, rhythm, or momentum, though with occasional forced wit. She grinds it out paragraph by paragraph, stilted exposition by stilted exposition, reaching something like competence toward the end of the interminable series. At the level of the sentence, she’s no Lewis Carroll. Any tic is going to get repetitive at this sort of length, but just to pick one, Rowling can’t just let people say things, but must adverbialize. Chunks of dialogue roll by like this:

‘The owls… aren’t bringing me news,’ he said tonelessly.

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Aunt Petunia at once.

‘No more do I,’ said Uncle Vernon forcefully.

‘Let’s go!’ said Lupin loudly.

And on like that for 500 pages until they get dropped into the Pit of Doom or whatever it may be. That’s one reason that I don’t think the Harry Potter books will end up as any sort of classic of children’s literature. It’s suddenly going to strike the next generation of children that they’re unreadable.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell