By 1983 the cult of Star Wars became stronger with the release of the film series’ third installment Return of the Jedi. The movie dramatizes the defeat of Darth Vader and his evil Galactic Empire and the victory achieved by heroes Luke Skywalker and The Rebel Alliance. Even with that upbeat conclusion fans still wanted more. Just like a real war, there could be no easy way to permanently defeat something as massive as The Empire. The Rebel Alliance’s vast network of grass roots militias couldn’t transform instantly into the diplomatic Alliance of Free Planets. After Jedi decades would pass before Lucasfilm made any tangible effort to confront these issues. During that interim a crew of comic book creators took the reins of the Star Wars saga and steered it into emotional and conceptual places that its originators and many fans never could’ve imagined.

At the end of 1983 writer Mary Jo Duffy (aka Jo Duffy) took over Marvel Comics’ Star Wars series. Duffy’s work was initially a close copy of the narrative tradition from the films with the addition of a few extra characters and locales. Even these were similar to George Lucas’ creations. The early Marvel Star Wars artists followed suit. Ron Frenz, Al Williamson, and Tom Palmer turned in workman-like efforts rendering the main characters in a style that clearly emulated the physical appearance of the Hollywood stars who portrayed them. These predictable stories were for Star Wars diehards who needed a quick fix until the next official movie installment hit theaters. The 70th issue of Star Wars inaugurated Duffy’s run. It kicked off a brief story arc that bore close resemblance to Jedi with a quest to find a carbonite-imprisoned Han Solo, various forest settings, fuzzy little critter sidekicks The Lahsbees, and the decadent/fuchsia skinned/purple haired Zeltrons.

The latter aliens proved to be the first sign that big changes were in store. The flirtatious Zeltron adventurer-thief Dani and her equally hedonistic brethren had a streamlined, athletic appearance not unlike the figures popularized by 1980s graphic designer Patrick Nagel. Dani proved to be a match for Princess Leia Organa’s beauty, combat abilities, and wit, a dynamic that made both characters more interesting. The complex relationship between Dani and Leia was a radical contrast for SW’s previously male-dominated plot points. Even with Dani and the Zeltrons, Lando Calrissian’s adventures infiltrating a criminal gang, fish-man/martial artist Kiro of Iskalon, and other strange Duffy originals Star Wars issues 70 to 88 were mired in Lucas-style story elements.

The collaboration between Mary Jo Duffy and artist Cynthia Martin would revolutionize Marvel’s Star Wars beginning with issue 94. Before then the 89th, 92nd, and 93rd issues of the series set the stage for the Duffy/Martin run. 89 featured work by guest creators writer Ann Nocenti and artist Brett Blevins (who had recently collaborated with Duffy on The Saga of Crystar Crystal Warrior). Their story “See You In The Throne Room” resembles little else in the SW canon.

Nocenti takes outrageous liberties with Luke Skywalker’s character. In the midst of the post-rebellion chaos on the planet Solay, Skywalker tries to squeeze in a quickie with a sexy fellow rebel, he insults nearly all of the other characters, and fraternizes with one of the planet’s shadiest hustlers. Some scenes occur in sleazy go-go bars while others include graphic depictions of assaults and muggings. Objectivist street urchin Scamp is a great supporting character. The impoverished moppet’s callous indifference to fellow citizens and the screwed-up relationship she has with her drunken self-centered father add to the other elements that make this one of the series’ most mature and provocative stories. The tale ends with a shocking act of anti-heroism.

Skywalker’s personality isn’t all that gets mutated here. Blevins doesn’t even try to make the character look like Mark Hamill. On the issue’s cover his appearance is similar to that of a drugged-out refugee from a renaissance fair. It’s a perfect distillation of this story’s emotionally exhausted Jedi Master. The script also works hard to justify the dark change in Luke’s personality. It’s clear that Nocenti didn’t view political upheaval as a major source of progress. A dejected Skywalker voices Nocenti’s criticism of the regressive chaos created by revolutionaries who are obsessed with the act of revolting against oppression while having no understanding of liberation’s purpose: “We toppled another figurehead. So what? It’s not enough to be against something. One must be for something.”

Star Wars 92 featured a 40-page Jo Duffy epic called “The Dream” illustrated by the celebrated fantasy artists Jan Duursema and Tom Mandrake (Warlord, Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, Fury of Firestorm). The story comments on the deep, often unexpected effect that war has on family dynamics and gender identity. The most powerful element of this issue is the cover art, a collaboration between Cynthia Martin and Marvel’s penultimate 1980s avant-garde visionary Bill Sienkiewicz. This shows part of a dream sequence where a faceless/distorted Skywalker fights Darth Vader while surrounded by an abstract haze of paint and ink. A spectrum of silvers, smoky grays, and blacks splatter the haunted tableau. It’s the single most unrealistic cover of the series. The impulsive choices made by several principal characters result in a climax that’s just as offbeat as the cover art.

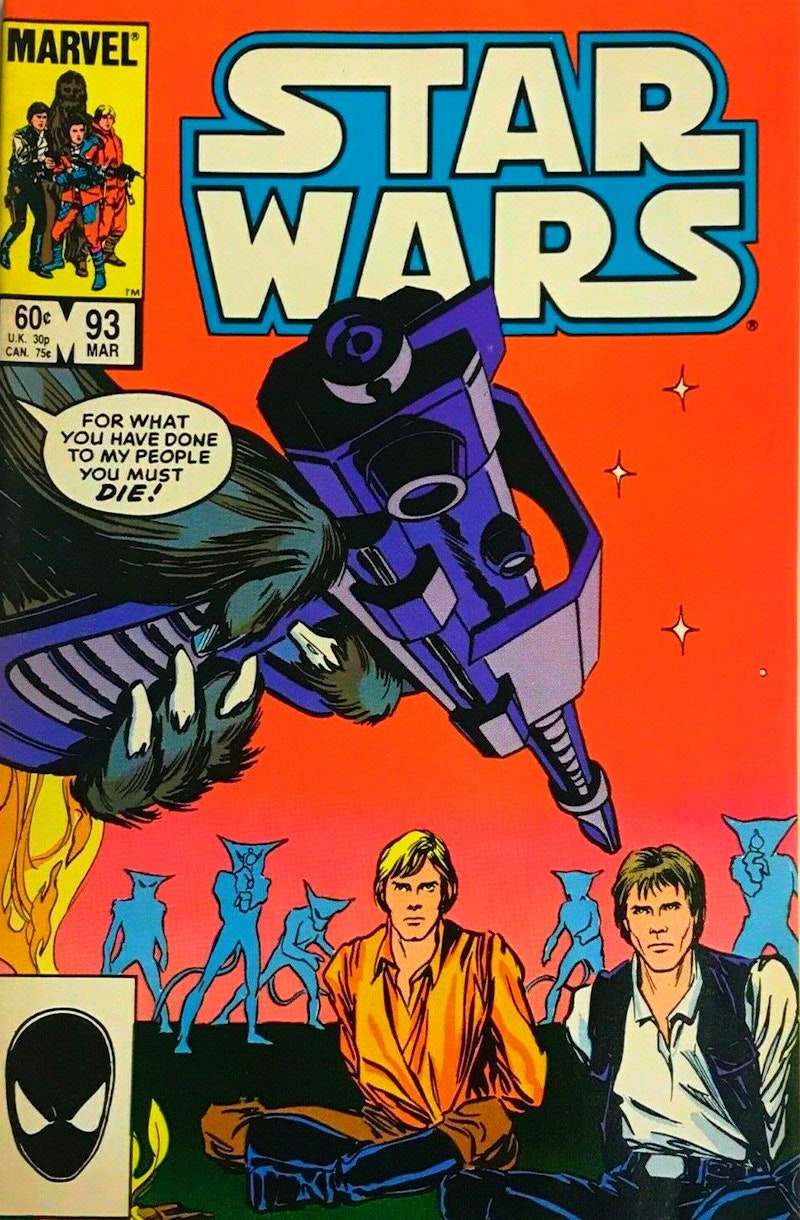

“Catspaw” was the politically-charged Jo Duffy story featured in SW 93. Petra Scotese’s vibrant coloring is a big part of this issue’s one-of-a-kind visual experience. Sal Buscema and Tom Palmer provide photo realistic interior art, but not even that could dilute the dreamy dayglo feel of this adventure. The Cynthia Martin cover art (her first solo work on the series) benefits the most from Scotese’s burning crimsons, purples, blues, and oranges. This was the polar opposite of the muted color palette found in previous issues. Martin’s depiction of the story’s protagonists uses only a modicum of detail as she takes the irreverence of Blevins and Sienkiewicz to a whole new level. She creates post-impressionistic versions of Luke Skywalker and Han Solo, not caricatures of their Hollywood alter egos (Hamill and Harrison Ford).

A confusion of guerilla warfare (similar to the chaos found in SW 89) controls the Duffy script of “Catspaw.” Still cleaning up their decimated public infrastructure, an alien race of cat people lives side by side in twin shell shocked communities in a remote corner of the dead Empire. Their great anti-climax drags on as civil war factions are pit against each other by a double agent with Empire sympathies and a mysterious identity. Throughout the Duffy/Martin Star Wars run such exploitive villains command a brutal presence and the worst of them was yet to come.