I am obsessed with glamour. Just last Saturday I went to an opening reception of new work by this super major artist named Richard Prince at Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea, New York. Talk about GLAMOUR! Black limousines. Stilettos. Red lipstick. Elaborate, extremely expensive outfits. Champagne. Paparazzi. Calvin Klein models. It was like a who’s who of models, Super Rich Dudes Everybody Needs To Sleep With To Get Ahead, and other glamazons.

But what happens when luxury and glamour are put up against war and bombs? What is the relationship between images of glamour and terror? These are the questions posed by Martha Rosler’s solo show, Great Power, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery, which ran from September 6 to October 11 in Chelsea. The show, Rosler’s first solo exhibition since she joined the gallery in 2005, featured new work in diverse media, from photomontage to video and sculpture.

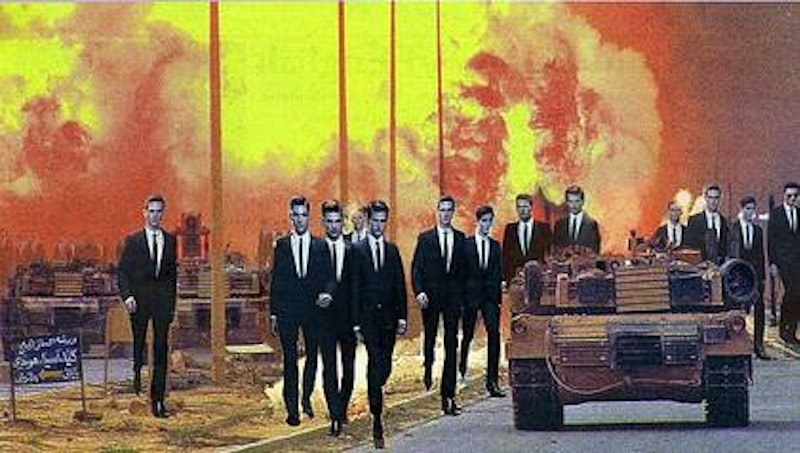

I thought it was totally major. One really fierce piece was "Invasion" (2008), which shows an army of super hot male high-fashion models strutting down this destroyed third-world street dressed to the nines. What makes the picture work is that these smokin’ hot dudes are pinned up against the smokin’ red clouds of explosions. Oh, and then there’s this menacing army combat vehicle that’s just like sitting there or whatever, setting up the visual contrast between the chicness of the dudes and the terror of the bombs.

I don’t know if any of you have read any Bret Easton Ellis beyond Less Than Zero, but that models-as-terrorists photomontage really made me think about Ellis’ extremely long terrorism novel Glamorama, my favorite novel of all time. In that fat book, the terrorists are fashion models who conceal their explosives in Louis Vuitton and Prada bags.

WORK! If only I thought of it first.

In light of Ellis’ novel, I think "Invasion" destabilizes the magic of glamour—you know, as in, shows you what it looks like from the other side of the mirror, a theme that is visited and revisited throughout the exhibition.

Another fabulous piece is "Point and Shoot" (2008) which features this completely fiercerized bitch in the foreground, possibly a celebrity, dressed in an amazing silver gown, carrying this camera and looking through the image at you. That image is smashed against background scenes of policing and disorder in a small Iraqi village. Soldiers armed with guns order these Iraqi dudes around, and the glamorous red carpet image disconnects with the only other woman in the picture who is dressed in a black habit.

Here’s the catch: the line of dudes seem to be more enthralled with the tranny fierceness of the woman in the foreground than with, you know, the safety and well-being of the woman in the background being bullied by the soldier with a gun. Apparently glamour—as an optical illusion, as magic, as surface quality, as feminine characteristic—trumps all.

The most disorienting piece in the show is a ginormous prosthetic leg. When you go in the gallery, "Prototype (Freedom is not Free)" (2006) just like fuckin’ dangles from the ceiling, moving and kicking back and forth. I guess it’s supposed to highlight the effects of the war in Iraq on us humans or whatever.

Great Power seems to be about the Iraq war—that’s undeniable. But if luxury, glamour and high-design are considered a central aspect of Rosler’s project, the show ultimately reveals the complexities of the glamour system. Even that giant prosthetic leg features four images of high-heeled shoes. So in addition to being a violent protest against the casualties of the Iraq war, the show is equally an attempt to crush glamour’s, and by extension consumerism’s, sexy but disorienting shimmer.

To gain entry to the show, visitors needed to deposit a quarter into a turnstile, guaranteeing them access into the world of glamour. Typically entrance to gallery shows is free. Only museums charge an admissions fee. Organizing Great Power around consumerism—“hey bitches, not even art is free anymore!”—brings home Rosler’s point that we are all implicated in the act of luxury, consumption and glamour.

Therein lies the interesting characteristic of Rosler’s art: it’s commercial, high-end, democratized and public all at once. Anyone can make a photomontage. Anyone can take a free copy of the works. But not everyone has the financial prowess to buy a real one.

Rosler, who lives and works in Brooklyn, obtained an M.F.A. at the University of California, San Diego in 1974. Her work largely addresses consumerism, social life and the public sphere. She has participated in a number of large-scale exhibitions, including WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution. The images from Great Power are recaps of her series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful (1967-72), which forced war images against high design and domesticity.