The accusations leveled against Harvey Weinstein have prompted the media to rediscover the “crimes and misdemeanors” of people like Woody Allen and Roman Polanski, calling for the removal of any accolades or awards they’ve received. As much as they deserve attention, the details of Allen and Polanski’s transgressions are not of my concern here. What these incidents bring into the foreground is an important question: can you separate an artist from his art? We must also ask, is there a value and beauty in art (all forms of art: literature, film, painting, sculpture, and music) if the artist himself is a deplorable person?

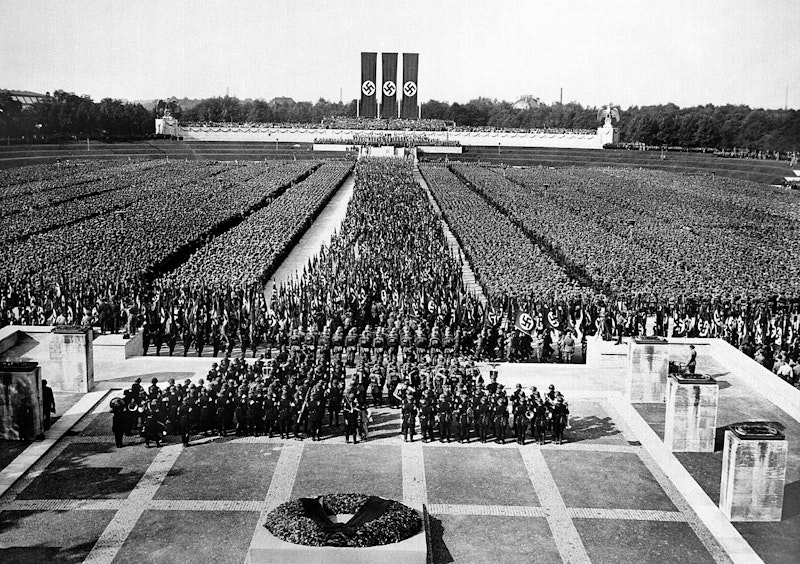

This needn’t be limited to the artist only, or to sexual assaults and various sexual transgressions. We may include thinkers, philosophers, and scientists. Should we read and consider any of Heidegger’s philosophy, especially since he has made such an impact in the field of phenomenology that cannot be ignored, even in the strange juxtaposition to his anti-Semitism? Or does his work inherently contain anti-Semitism? Should we admire Leni Riefenstahl’s innovative camera work in the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will, even if she consistently denied throughout her life that she was making a propaganda film and was ignorant of Hitler’s realized intentions? Should ethics come before aesthetics?

There are two parts to this problem—one deals with the artist himself, and the other with our relationship to the artist as well as their work. We must differentiate between an artist who creates work that may be deviant and unpleasing in nature but is a “good” human being, and an artist who creates works of great beauty but is a deviant or “bad” human being.

It’s easier to deal with an artist who creates deviant work but is a good human being. We choose to either look at it or not, and we may even be perplexed as to why this person is driven to create something strange and alien, and yet they themselves are quite the opposite of that creation. But being perplexed does not involved a moral conflict for viewers. The relation with this kind of an artist remains in the sphere of curiosity and a desire to get into their mind in some way.

The other type of an artist, a bad human being creating beautiful art, is harder to deal with precisely because we enter into a moral conflict whether to admire and value their art and deem it a necessary precedent that will serve as an inspiration for later creation. The relation with this kind of artist is vague and filled with tension because it represents that tug between ethics and aesthetics.

There are people who have no internal moral conflict whatsoever in this regard. These same people live for the shock and rattling of tradition, which they hope to dismantle. For them, the order of things is just an illusion and anyone who espouses tradition is quaint and backward, not to mention repressed. As humans, we have many difficulties in looking at evil completely. We look for excuses, and art gives us a perfect excuse to absolve ourselves from moral thoughts and decisions. At times, our admiration for the artist and their work is subjective and any view of their work is directly correlated to the blindness of their actions or ideas. Some go as far as to become sycophants and, implicitly, take on the culpability of the artist because they desire to be affirmed in their own beliefs.

We cannot control what an artist does, and it’s not our fault if they have committed crimes or have unsavory ideas. But we do have control how we react and whether we are even trying to reconcile these disparate aspects of the artist. This inevitably leads us to ask who the artist is and what their identity is composed of. Are they real and how much of themselves are they revealing? Oscar Wilde wrote, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell the truth.” On the other hand, Jean-Jacques Rousseau claimed that when man takes off the mask, everything about him is revealed. We (and the artist as well) use masks metaphorically in order to escape that looming vulnerability when we are in the company of others.

In The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote about the duplicity of the masks that we create. If we reveal ourselves by taking off the mask, then will we not hide and participate in an infinite creation of false selves, duplicating one mask after another. Does “true self” even exist or are we living in a delusion that we will know ourselves?

There’s no escape from the duality and contradiction of the identity that’s hounding us. Putting on a mask means that there will be a temporary death of the unmasked self. The unmasked self seemingly has no power, and the mask allows man to get closer to the divinity within and outside of himself. The divine, however, does not necessarily have to be linked to the good, or the angelic. More often than not, the aim of a masked man or woman is to become possessed by the mask. Terrified of demons, humans began to identify with the demonic power, which in turn totalizes and limits their being. The duality that’s human and bestial is always present in all of us, and just as an artist has a choice between the two, so do we in our relation to art and artist. Is the artist two different people, or personae, and this is the only way they can function? But here, already we are entering into the territory of absolving the artist of their bad deeds.

Is there some balance that we can reach in this dilemma? Will ethics and aesthetics always be opposed? Works of art cannot and should not be disregarded by the fact that they may have been created by a bad person. However, we have a choice not to engage in a cult of personality in which we mindlessly slobber infantile admiration on a particular artist. We have a choice to not make them into perfectly preserved marble sculptures of gods to whom we look upon and worship in some pagan and tribal way.