DC Comics’ schizoid villainy reached the peak of its power with Kobra. This fiend’s deadly attempt to enslave the world was driven by mutations of family ties and morality. The story of Kobra’s life and crimes fused ideas from Dumas’ The Corsican Brothers, the pagan weirdness of Eclipso, and a fractured conscience that recalled Two-Face. His tale is told with an empathy that’s rare in any villain comic story published before or since the character’s February 1976 debut.

Kobra (a.k.a. Jeffery Franklin Burr) and his brother Jason Burr were born as conjoined twins. At an early age they were surgically separated, then raised apart after a snake-obsessed criminal cult abducted the infant Kobra in response to an esoteric prophecy. As the child grew to adulthood his captors groomed him to become their god-like leader while keeping him hidden in a secret Himalayan lair. Could this element be a reference to the volatility that Central Asia has endured as a consequence of western imperialism? That’s debatable, but the injustices that caused Kobra’s transformation from random kidnap victim to pompous monster are undeniable. Just as Idi Amin and the Taliban were baptized in the fires of western oppression, the French Revolution was shaped by violent classism, the trauma of sex abuse and bad parenting scarred Charles Manson with a wretched disposition, negative powers beyond control turned Jeffery Burr into Kobra.

Romantic betrayal is another inspiration for Kobra’s power-mad misanthropy. His sanity cracks under the weight of a mistrust which ruins his idealized view of Natalie Crawford-Thomas, Kobra’s only lover and the only person ever to relate to him outside the context of super-villainy. She’s a globetrotting socialite with a checkered past and a physical appearance eerily similar to that of Melissa McNeil, Jason Burr’s girlfriend. The possibility that Crawford-Thomas and McNeil could be the same person is an endless torment for the villain.

Kobra’s schizoid element and his empathic element are one and the same. A side effect of Burr and Kobra’s status as twins is a telepathic link which joins the brothers’ nervous systems. Like the main characters from The Corsican Brothers, when Burr feels intense pain Kobra is shocked by the same sensation and vice versa. This leads the brothers to protect each other even if it means compromising their physical safety and polarized personal values. The scruffy/wise-cracking college student Burr is most often portrayed as a protagonist yet he does everything in his power to avoid killing his megalomaniac brother.

In Kobra no. 3 (July 1976) the twins share their first major confrontation thanks to NYPD lieutenant Ricardo Perez and his do-or-die mission to capture Kobra. Though the snake lord’s main headquarters are in Nepal, he also commands bases of operation all over the globe with one of his biggest satellite hide-outs situated in the slimy bowels of the NYC sewer system. Perez uses deceit and half-truths to manipulate Burr into working as a decoy to draw Kobra out of hiding, a negligent scheme that fails miserably and nearly gets the “good” brother killed. Overwhelmed by anger and resentment Burr punches Perez in the face, calls the cop a “pig,” and loudly proclaims that Kobra is the Jesus Christ of nihilism.

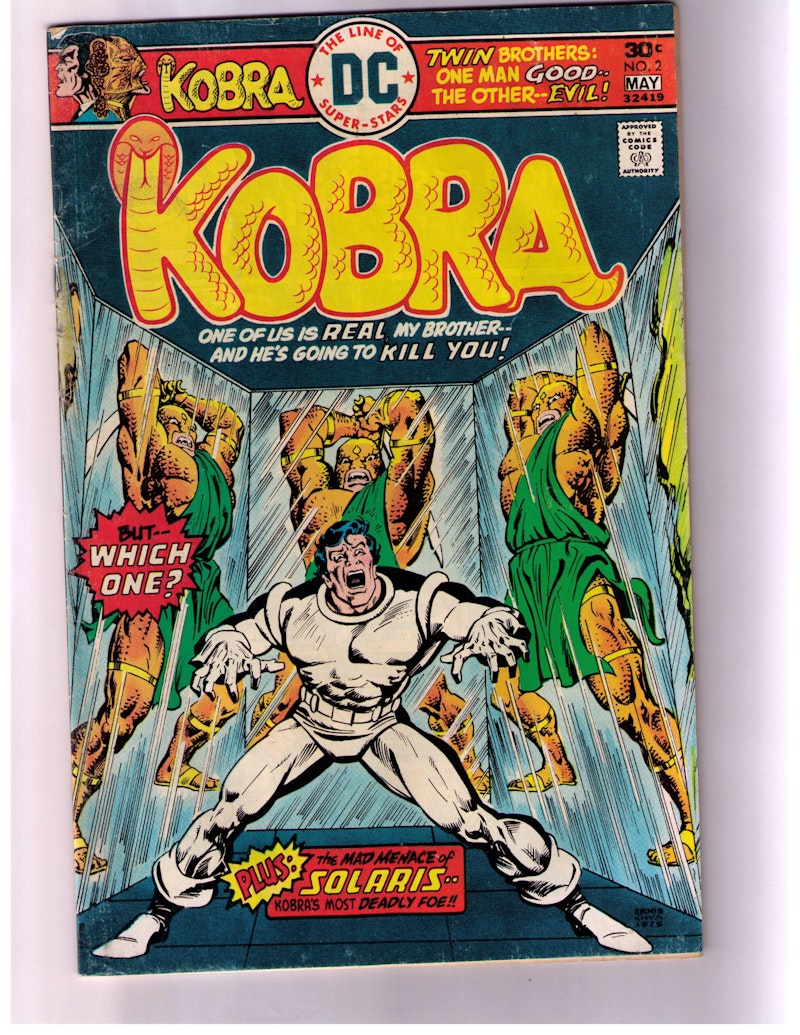

Jack Kirby, sci-fi/fantasy luminary Steve Sherman, and Martin Pasko jointly created Kobra. For Pasko the character’s eponymous series was the first major work of his career. His scripts displayed the ambitious sprawl that would make him an in-demand comic writer throughout the 1980s. As Pasko’s plot twists became progressively dynamic Kobra’s interior art team evolved, changing in style and personnel with each consecutive issue—Kirby, D. Bruce Berry, and Pablo Marcos drew the first issue; the second was drawn by Marcos and Berry; the third had the surreal design experiments of Keith Giffen, Terry Austin, and Dick Giordano; issue 4 featured an eccentric collaboration from super hero comics icon Al Milgrom and two novice artists, Pat Gabriele and Lowell Anderson; 5 was illustrated by Frank McLaughlin and Rich Buckler (around the same time Buckler’s mercurial anti-hero Deathlok The Demolisher became a cult fave in Marvel’s Astonishing Tales). Finally, for 6 and 7 and the anthology title DC Special Series no. 1, the harsh visions of Michael Netzer and Joe Rubinstein put a fiery end to the original Kobra plotline. Ernie Chan (Conan The Barbarian, Power Man & Iron Fist) contributed the series’ most iconic covers, including the disturbing/masochistic art that adorned the title’s debut issue.

With sibling arch-enemies locked in a stale-mate, Kobra’s early stories come from a philosophical perspective that’s a perfect match for today’s morally confusing political landscape. From the gullible lemmings obsessed with fake news, to the shallow futility of culture wars, to the specter of the mental health crisis, the 21st century teems with the chaotic nuance of a world where villainy can easily become a twist of fate, not the premeditated life choice of criminals. The family dramas of Kobra and Jason Burr remind us that the symbiosis of “evil” and “good” churns at the core of all conflict.