The rewards of picto-fiction are strange and awesome. It appeals to base visual sensibilities and highbrow literary interests while packaged in the modest physical form of a comic book. The medium has produced some of sequential art’s most challenging and experimental works.

Terror Illustrated no. 1 (EC Comics; November-December 1955): E.C. Comics was experiencing its last gasp as a comic book publisher when the first issue of Terror Illustrated rolled off the presses. Shortly before that many of the company’s comic titles were demonized by child psychologist/anti-comic activist Dr. Frederic Wertham and his book Seduction Of The Innocent. Terror Illustrated presented new exclusive stories and versions of earlier tales newly re-drawn and re-written in the picto-fiction format. EC’s embrace of picto-fiction had artistic and practical purposes. By printing Terror Illustrated as a magazine with a cover blurb specifying its intended adult audience the company avoided the scrutiny of Wertham and C.C.M.A. censors.

The ultra-violent/full color EC horror comics were created by WWII vets coming to grips with mental scars and drastic cultural changes that emerged during the post-WWII era. While Tales From The Crypt, Haunt Of Fear, and other early-1950s EC titles were visceral reactions to neurosis, Terror Illustrated was a horrific but contemplative look at social ills and philosophical questions. “Rest In Peace” by Jack Oleck and George Evans is featured in the first issue. It’s a tale of disturbing events that entangle three friends in a deadly drama. The story centers around the question of when it’s appropriate for someone to intervene in the personal problems of others.

Regardless of how gritty they were, EC horror comics delivered escapist fiction first and foremost. They had political subtexts, but those were buried beneath detailed multi-colored drawings and scripts steeped in dark/ironic humor. Picto-fiction was a form of interpretive fiction. The illustration was B&W, subtle and shadowy. Occasional duo-tone color bursts created a mystical dynamic. Lettering flowed around the art in ways that were antithetical to the boxy graphic design commonly applied to comic text layouts. The picto-fiction aesthetic turned EC’s gore-crazed nightmares into mutant meditations on morality’s fluid nature.

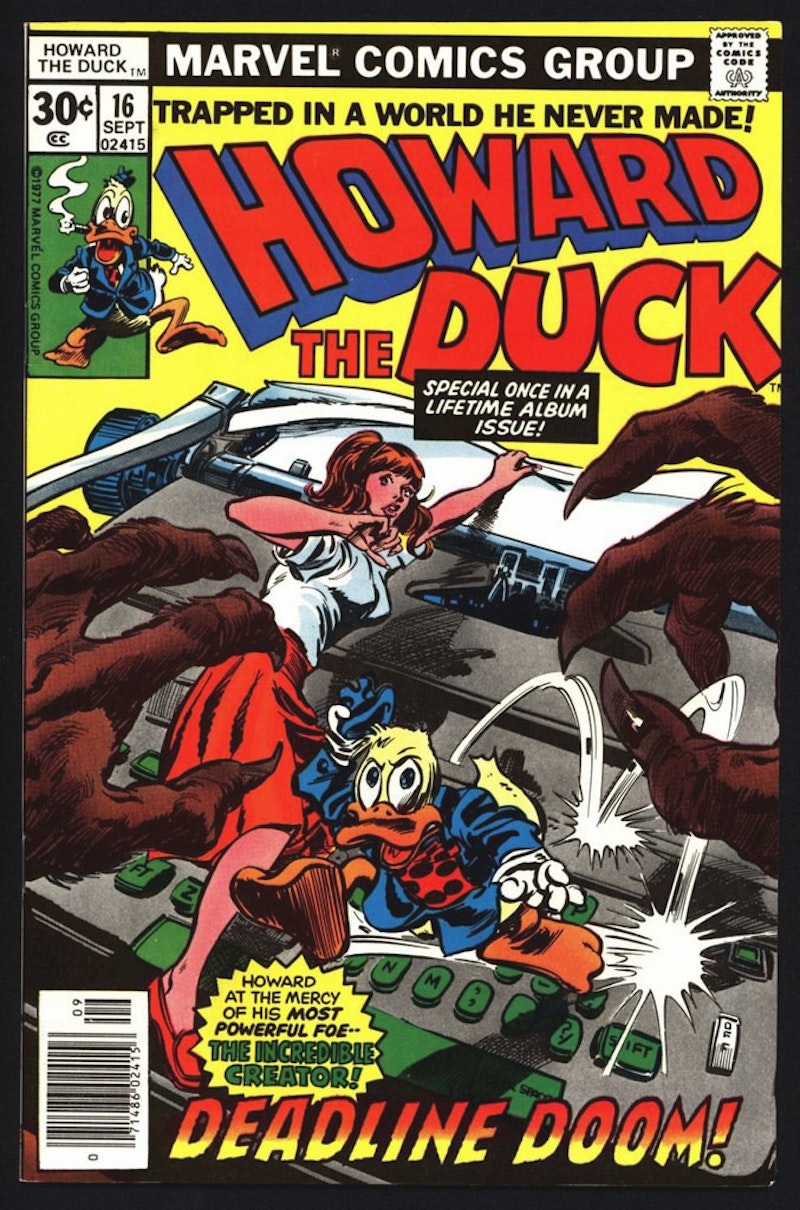

Howard The Duck no. 16 (Marvel Comics; September 1977): The ground-breaking Marvel character Howard The Duck kicked off the big comic trend of adult-oriented titles starring anthropomorphic animals (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Cerberus The Aardvark, Neil The Horse, Usagi Yojimbo, etc.) This humanoid fowl from outer space first appeared in Adventures Into Fear 19 (December 1973). He was created by writer Steve Gerber and artist Val Mayerik. Sarcastic and streetwise, Howard was the Marvel Universe’s perennial outsider, unlucky in love, and perpetually mad at the world and its rulers, “the hairless apes” (aka all humans).

The 16th issue of Howard’s eponymous title featured the picto-fiction saga “Zen and The Art Of Comic Book Writing: A Communique From Colorado.” The story’s told in a succession of double-page spreads teeming with symbolic imagery. The text is dominated by an argument between Gerber the creator and Howard the creation. Howard represents the voice of reason. Gerber’s lines come from the perspective of an insecure, spacey nerd stressed out by what the comic’s cover blurb describes as “Deadline Doom.” Each double-page spread features work from different artists, another element that solidifies the story’s symbolist angle. “Zen…” is an animated pastiche of satire, surrealism, anti-authoritarian rhetoric, Harvey Pekar-ish candor, and dramatic 1970s-style existentialism.

Fury Of Firestorm Annual 2 (DC Comics; November 1984): Science fiction writer Arthur Cover and Amazing Spider Man scribe Gerry Conway teamed with artists Rafael Kayanan and Ernie Colon to create one of the few picto-fiction stories about a superhero. This untitled oddity gets off to a clumsy start before kicking into high gear midway through. The book’s first half finds the writers struggling to set up the plot and its connection to The Mage, an alien villain/psychological sadist with powers similar to Nightmare On Elm Street’s Freddie Krueger. The action is driven by painful hallucinations that plague the titular main character, a nuclear-powered costumed crusader with hair made of fire who has a dual secret identity—high school student Ronnie Raymond and physicist Dr. Martin Stein. The story’s poetic high points arrive when Cover & Conway describe Raymond’s role in a basketball game where his school team plays against a rival squad comprised of entities who look like Firestorm’s arch foes. In another crucial moment a serpentine strand of text surrounds Firestorm. This scary prose slithers across the page during the hero’s worst mental breakdown.

The art from Kayanan & Colon is relentless. From horrific monsters to thunderous explosions, to vivid depictions of 1980s fashion and pop trends, the artists keep everything exciting even while the writers fumble with syntax. For fans of Firestorm this is an essential, crafty examination of the hero’s deepest fears. For everyone else, Fury of Firestorm Annual 2 stands as a fascinating testament to picto-fiction’s strengths and limitations.