Several years ago I walked into a downtown Montreal bookstore and asked them to order copies of three anthologies that together reprinted all of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories. The elderly staffer behind the counter seemed skeptical. The store did a lot of business with students from a nearby university and was what you might call academically-oriented, if not upmarket. But I’d been given a gift certificate to the place, and I wanted those Howard books. As I said to the staffer, I believed Howard would be the next pulp writer to be rediscovered by the literary world. Time having passed, I’ll point out that in 2009 Penguin Modern Classics published Heroes in the Wind, a collection of Howard’s fiction. I consider myself vindicated.

It’s logical to me. A few decades ago overlooked pulp mystery writers were claimed by the ever-sprawling canon of American literature. Authors like Dashiell Hammett and Jim Thompson were read and re-evaluated as prose artists. Some of the virtues of Hemingwayesque prose—clarity, speed, directness—are virtues of good pulp prose. Not surprising that among the millions of words spilled in pulp magazines a few are remarkably well-chosen. And other genres should now be given reconsideration as well.

Some fantasy and science fiction has always had literary ambitions, especially in the last 50 or so years after the “new wave” of writers like Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delany, Joanna Russ, and M. John Harrison came along. But before them the mass of pulps produced writers with ambitions of their own—just think of someone like Ray Bradbury. Or Theodore Sturgeon, a well-regarded humanist science-fiction writer who’s already gained a kind of literary immortality as the inspiration for Kurt Vonnegut’s Kilgore Trout. There was more ambition, more boundary-pushing, in old speculative fiction than used to be acknowledged.

Philip K. Dick is increasingly recognized as an important writer, if one with a bad ear for prose. The same for H.P. Lovecraft, for all his racism (though unlike Dick some—and I’m one of them—rate Lovecraft’s prose highly). Isaac Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy has made it into Everyman’s Library. Longtime pulp writer Jack Vance had a glowing profile in The New York Times Magazine a few years ago. Science-fiction critic Gary K. Wolfe has edited a two-volume set of nine short science-fiction novels from the 1950s for the Library of America, which also publishes editions of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes and A Princess of Mars.

We’re living in a science-fictional world, and the genre’s now more mainstream. At the same time, there’s always interest in pulling forgotten authors into the modern spotlight. Sometimes that’s a good career move for an academic or critic, sometimes it grows from a reader’s desire to let other people in on a favorite writer. I assume we’ll be seeing more pulp science fiction and fantasy writers in the canon, or at least into a state of demi-canonicity.

If so, who? Science fiction already has an active fan community that keeps writers like Heinlein and Clarke in print; can those writers make the jump to self-consciously “literary” readers that Philip K. Dick has managed? You can get some names from the nine novels Wolfe put together. Heinlein and Sturgeon. Leigh Brackett, who in addition to her novels and short stories co-wrote movies including The Big Sleep and The Empire Strikes Back. Alfred Bester, whose The Stars My Destination and The Demolished Man brought modernist experimentation with text layout to science fiction. Fritz Leiber, an accomplished stylist. Several writers, Richard Matheson, Algis Budrys, James Blish, Frederick Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth, who wrote tight prose and used genre conventions to get at themes that mattered to them.

That’s a good start. It strikes me that, unlike Asimov or Dick, these writers are mostly strong at the sentence level either especially direct or unusually innovative, if not lyrical. Bearing that in mind, I can think of a number of other writers who might be ripe for rediscovery. Here are seven more writers who all began their careers before 1960:

Avram Davidson was an active science fiction and fantasy writer from the late-1940s until his death in 1993. His prose was baroque, witty, and highly ironic. His lushly-imagined fictions often drew from a rich grasp of history and high culture, as in his tales of the Eastern European occult investigator Doctor Eszterhazy or his novels of Vergil Magus, a wizard based on medieval traditions of the Roman poet. Some of his stories, like the unsettling “Dagon,” show a tremendous grasp of form and subtlety.

Zenna Henderson began writing in the early 1950s, and was active for 20 years before her output began to slow; she died in 1983. A short-story writer, she’s best known for her linked series of tales about the People, a group of aliens stranded on Earth. Personally, I was surprised at how much I enjoyed her non-People collection The Anything Box, tightly-written fictions that sometimes turn lyrical, often using science-fictional elements to talk about children and families.

Raphael Aloysius Lafferty barely counts here chronologically, as his first (non-SF) story was published in 1959, and he turned to genre only from 1960 on; he retired from writing in the mid-1980s, and died in 2002. Like Davidson, though, he was always something of an oddball. His stories and novels were idiosyncratic, using unexpected diction and (often) the rhythms of an oral storyteller. A conservative Catholic equally at home imagining Thomas More reincarnated in the future or The Odyssey in space, he was less concerned with traditional plot than language and the sheer vigor of storytelling; he’s often described as a teller of tall tales. At his death, much of his work was unpublished, but in the past years his estate—with the help of Neil Gaiman, a big fan of Lafferty’s—has begun to get his fiction back into print.

Abraham Merrit was an old-fashioned pulp adventure writer whose stories have an uncommon intensity. He broke into print in 1917 and wrote at least into the mid-1930s, dying in 1943. His stories have the flatness of adventure fiction, but also a dizzying surrealism, a stream of constant invention that matches the restlessness of Merrit’s prose.

Catherine Lucille Moore broke into print in the 1930s, swiftly gaining a reputation with stories following two characters, the science-fictional scoundrel Northwest Smith and the high-fantasy warrior-woman Jirel of Joiry. From 1940 on, she frequently wrote in collaboration with her husband Henry Kuttner, also a respected science-fiction writer; she largely stopped writing after his death in 1958, and completely stopped after remarrying in 1963. She died in 1987. Moore’s perhaps best known for her Jirel stories; the character’s often described as a distaff Conan, which is accurate to a point but undersells the real strangeness of the Jirel tales. The prose is lurid, vivid, and surprising—and like Howard in fusing action with character in a feverish heat. There’s also her novel Doomsday Morning, a political satire set in an America that’s fallen apart in the distant year 2000.

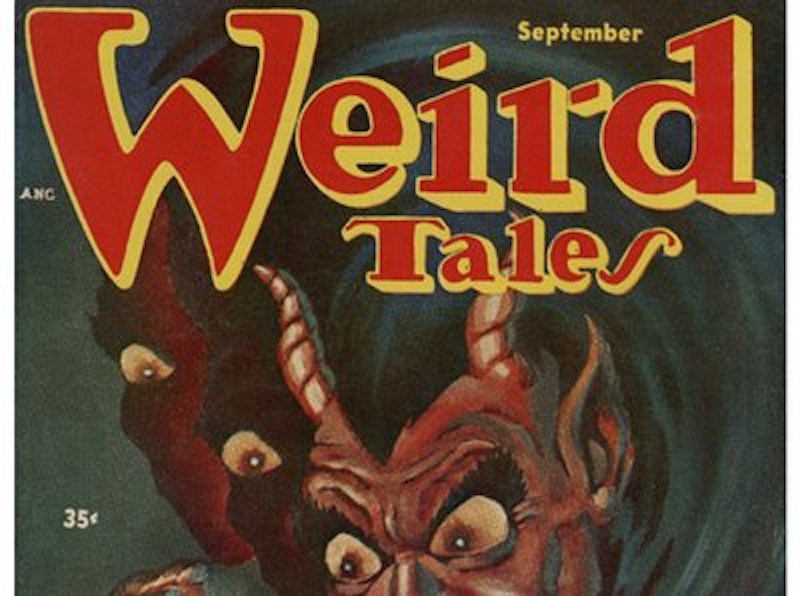

Clark Ashton Smith was a poet almost more than a prose writer. Largely self-educated, as an adolescent he wrote novels for himself and sold his first book at 17, in 1910. He spent much of the next two decades writing poetry, finally turning to the pulps to support himself. He became the third member of “the big three of Weird Tales,” along with H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. In my opinion, he’s the best writer of the three, combining a fine ironic sense with a florid vocabulary. His sensibility may be the farthest of any of these writers from the modern day, in that he reads like a prose Swinburne, romantic and decadent but a little old-fashioned. His settings ranged from a decaying Atlantis to the last days of human life on Earth, while his baroque style influenced later writers like Jack Vance and Fritz Leiber. Smith largely stopped writing in 1944, and died in 1961.

Cordwainer Smith was the pen name of Paul Linebarger, a soldier, diplomat, East Asia scholar, expert on psychological warfare, and godson of Sun Yat-sen. He had an early story published in 1928 at age 15, later published two non-SF novels, and returned to the genre in 1950 with a story that quickly became famous, “Scanners Live in Vain.” Between 1955 and his death in 1966 he focused on the future civilization of that story, publishing a novel and many short stories in the setting. He tried to bring techniques from Chinese writing into his fiction, and much of his writing had an unusually elliptical feel, implying a larger world with a greater history behind it than any given story directly described. His imagery was strange, using standard science-fictional ideas in weird ways.

Those writers would be my pick for overlooked authors ripe for rediscovery. Good stylists, idiosyncratic storytellers with strong individual voices. But who knows? There were any number of writers who passed through the pages of the old pulp magazines. Impossible to know what the future will value in art. Who in the 1950s would have imagined Penguin publishing Robert E. Howard? All I can say is that these are good writers. Sooner or later, that ought to matter.

—Follow Matthew Surridge on Twitter: @Fell_Gard