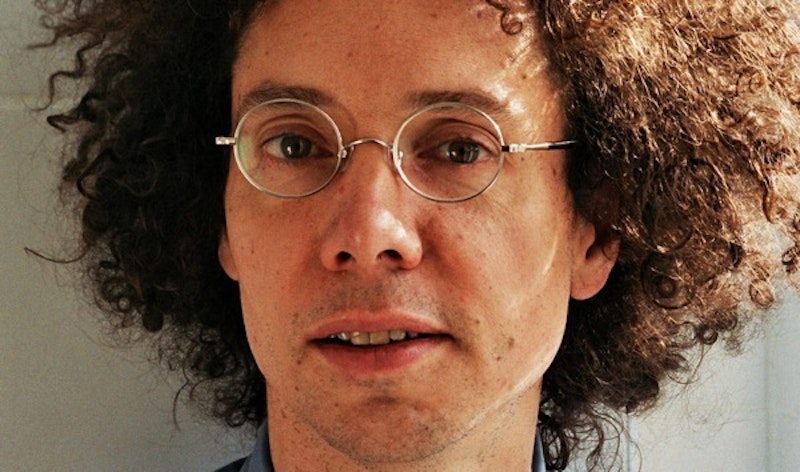

In last week's New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell, everyone's favorite social scientist, aims to answer the question of why more powerful forces occasionally lose to opponents unequal in numbers, training or ability. In typical Gladwellian fashion the essay is wide-ranging in its subject matter, flitting between biblical parables, guerrilla warfare, and girl's basketball. Also in typical fashion, the essay is absolute pap, resting on anecdotal evidence, which Gladwell inaccurately interprets to prove a conclusion, which, belying Gladwell's initial promises of shocking revelations, in fact turns out to be almost mind-numbingly prosaic. It is worth studying not because it offers any great insight into the subjects discussed, but because it offers a distinctly excellent example of the style which has turned Malcolm Gladwell into one of the most popular thinkers of the early 21st century.

Gladwell opens with an astonishing premise—according to a recent study, overwhelming military superiority is no guarantee of victory. In fact, in the last 200 years the “Goliaths” overcame the weaker “Davids” only a paltry 71.5 percent of the time. This is the sort of non-conventional wisdom that has become Gladwell's stock in trade: compellingly counterintuitive, and resting on an intellectual foundation more closely resembling tissue paper than granite. To anyone familiar with military history the division of opposing forces into “Goliaths” and “Davids” is an exercise in futility. What defines the “underdog”? Lack of numbers? By that standard the British were the underdog in the Battle of Omdurman, where a small army of British and allied soldiers armed with repeating rifles and machine guns slaughtered an army of 50,000 Sudanese heavy cavalry clad in Crusader-era plate mail and wielding wooden lances. Prior to 1941 the U.S. had the 17th largest Army in the world; do we consider them the underdogs in their conflict against Japan because Nippon could field more ships after their strike on Pearl Harbor? Or, like Admiral Hirohito, do we recognize that the manufacturing might of America was too much for a small island nation and grant the sobriquet of David to The Empire of the Rising Sun? These are only a pair of examples, but one could come up with literally dozens more. War is not an activity that can be easily reduced for the benefit of oddsmakers, and attempting to somehow aggregate hundreds of years of human conflict into a single point of data is absurd.

Having caught our attention with an opening statistic that unravels as soon as you look at it, Gladwell then goes on to misread the foundational text of Western civilization, explaining that the allegory of David and Goliath contains within it critical lessons by which a smaller, unconventional military might defeat a more powerful force. Like the earlier statistic, this reads well but is patently false. The Old Testament is not meant to be understood literally as a history of military conflict, and an accurate interpretation of the text clearly explains David's success in battle as being due to his position as the anointed of God and not to any particular ability on his part. The simplicity of his arms and tactics are not strategic decisions made by a burgeoning military genius, they are literary devices meant to express our powerless before the will of the almighty. In fact, David's strategy, to challenge Goliath to single combat, is a terrible one for a weaker force to adopt in the face of a stronger opponent, and is in fact the diametric reverse of what Gladwell suggests throughout the remainder of the article. David's success lays not in his abilities as a warrior but in his unblemished faith in the Lord almighty—a fine sentiment for believers no doubt but not, on balance, an actionable military principle.

After a whirlwind description of the Bedouin campaign against the aging Ottoman Empire during WWI we are back to the Redwood City girl’s basketball team, and their strategy of playing a permanent full court press with the intention of making it impossible for the opposing team to successfully inbound the ball. Gladwell believes this is the very height of tactical brilliance, an innovation which allows Redwood City's crop of less talented players to dominate more skilled teams, and which would revolutionize the sport if only the moribund gentleman controlling it were willing to take a chance on a something new. Sadly (although not shockingly) Gladwell appears as ignorant of the sport of basketball as he is of the fundamentals of war, and a few moments of clear thought suggest Redwood City's accomplishments are likely not duplicable at higher levels.

The range at which a nine-year-old girl can effectively inbound a basketball is limited, meaning (obviously) the defending team needs to defend less territory. By contrast, an adult (of either sex) will likely be capable of throwing the bar well past the half-court line and into the opposing team’s territory, expanding the area a defending team needs to cover. Moreover, an experienced adult is less likely to get flustered in the face of defensive pressure and commit an unforced turnover, either by throwing the ball away or holding it past the allotted five seconds. Far from a revolutionary tactic that has yet to infiltrate the remainder of the basketball-playing world due to the intransigence of the establishment, Ranadivé's strategy is little more than a cheap trick, primarily effective due to the physical and mental limitations of nine-year-old girls. One empathizes with the furious parents of the opposing teams, and also recognizes the futility in attempting to draw general maxims about an activity by observing those least proficient in its execution, the equivalent of watching a game of laser tag and trying to rewrite the army's counter-insurgency manual.

More critically it highlights the imprudence of comparing war, in all its violence, chaos and madness, to team sports. This is not simply a question of poor taste, although there is something fundamentally boorish about contrasting the mass slaughter of human beings with a game in which two groups of equally numbered folk try and toss a rubber ball into a hoop. War is vastly more complicated than virtually any other human activity that attempting to draw parallels between the two inevitably ends with the sketcher reduced to abject reductivism.

Having seduced us with a series of fascinating (if inaccurately depicted) anecdotes, the practical conclusions Gladwell draws are interesting primarily for how uninteresting they are. A positive attitude is very important to success, he tells us, though it would be difficult to find historical examples of warriors showing more passion than the Japanese during WWII. Also, it's important to be physically fit—the girls at Redwood City trained soccer style, running endless rounds of sprints (lord help us if Al Qaeda ever discovers Pilates). Beyond that there is shockingly little in the way of an answer to the question Gladwell had set out to explain, other than the endless refrain to act unconventionally, as if this in an of itself was some sort of guarantee of success. But then, this is the essence of the Gladwellian style—a series of seemingly (and actually) unrelated stories, picked from a variety of disciplines Gladwell is not particularly familiar with, synthesized into a series of banal, simplistic, compelling truths, wrapped in the pleasing veneer of eccentricity.

I also have a love of unconventional theories, particularly the one that Malcolm Gladwell, bestselling author and beloved thinker, doesn't have a damn clue what he's talking about.

The Gladwell Method

One part unrelated anecdotal evidence + Two parts misunderstood historical theories + One part mundane conclusions = The world’s foremost McSociologist.