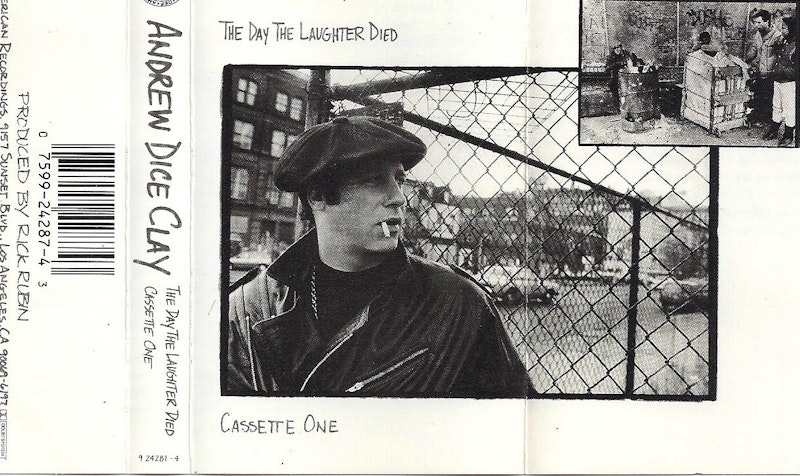

We can all picture Andrew Dice Clay's stupid haircut. His long sideburns curling in at his jaw, perfectly razored; his sleeveless leather jacket with its collar popped so high it hovers over his head like a rent-a-Dracula. I can even see the way he holds his cigarette, between his thumb and index finger like your typical moronic meathead. His cigarette is the prop that holds his act together.

(Later in life when Clay quit smoking, he would apparently hold a cigarette in his hand for five minutes—the duration it takes to smoke one—without lighting it, then he'd throw it away.) The cigarette is everything to the Diceman persona.

The Day the Laughter Died is a strange double album, released in 1990 and produced by Rick Rubin for Geffen Records. It was Clay's second album after Dice, which went Gold in the U.S. Dice had the sweet smell of success, and as a comic he sold out stadiums as a dumbed down version of Lenny Bruce. His vulgarities and charisma stage presence were dynamite in this country. PC mobs boycotted his shows. Sinead O'Connor cancelled her performance on SNL because she didn't want to share the episode with him. His unapologetically masculine behavior was controversial, but still, in 1990 everyone knew who Andrew Dice Clay was.

Which is why it makes absolutely no sense to release an album like The Day the Laughter Died as your follow-up. The album is nearly unlistenable, closer to Merzbow than Billy Crystal. Typically the sound of an audience member's footsteps stomping angrily out of the club would be edited out during post production—however, here it was embraced. People walking out is the main focus. Dice calls out anyone who dares leave his set, creating a scene for the audience to clean up, tearing viciously into his audience with all of his knives.

Dice could have chosen nearly any theater in the U.S. to record this album. With Rubin backing it, the funds were there. But instead he chose Dangerfield's, a small dive club in upper east Manhattan owned by his friend and mentor Rodney Dangerfield. The crowd seems mostly unfamiliar with Dice. I'm not sure if the show was promoted, or even announced. It was certainly unadvertised, only a few Diceheads in the audience. You can hear one person's lone laughter exploding throughout the special—that of Rick Rubin himself.

Dice's set is largely improvisational. Whatever passes through Dice's head is relayed and beaten into his audience to agitating extremes. Jokes about incest are common. Dice even accuses a father of being sexually attracted to his daughter who is seated directly next to him. The entire special is totally crude, off-putting, jarring, and offensive. It is absolutely one of the most revolting things I've ever heard.

By the end of the show, I was entirely lost in the world of Dice rambles. During the last ten minutes, Dice yells the words “Hour” and “Back” about a hundred times, screaming into the microphone, his voice cracking in desperation. After five minutes of bantering like a drunken maniac, he asks if the audience gets it. “You don't get it but you're laughing. That's what it's all about. Doesn't matter if it's funny. Doesn't matter if anybody gets it. . . You laughed again, you don't even know what you're laughing at. I don't know what I'm talking about, you don't know what you're laughing at. But it's funny.”

This quote sums up the entire special pretty accurately. The audience has no clue what Dice is talking about and Dice has even less of an idea. It's so absurd that it's funny, not immediately but as a slow burn, one that simmers and sticks with you, for better or worse.

What separates Dice from other moronic conservative comedians, like Adam Carolla, is his ability to turn the joke in on himself. As crude and offensive as he might be, Dice is playing a character. His character is an idiot, spewing nonsense about homophobia, misogyny, everything in the book. Not to spread hate, quite the opposite. His act isn't supposed to be taken literally. Unfortunately, many of his fans do take it literally. This is where the problem lies—less in Dice's act itself, more how his fans interpret and run with his words. Of course Dice feeds into this, taking advantage of his fans like Trump takes advantage of his mindless followers. Is his act wrong? Probably. Is it harmful? I believe so. Is it ridiculously absurd and enjoyable more than anything else? Definitely.

In an episode of his cancelled Showtime show, Dice finds himself wondering, “Would the world be a better place without me?” Tough question. My guess is probably not. I think he's giving himself a little too much credit. At the end of the day, he's a dinosaur in the world of comedy. If Dice hadn't come along, someone else would have. It's not too difficult to tell dirty nursery rhymes and berate an audience with toxic masculinity. The main difference between Dice and Larry the Cable Guy is that Dice made this superbly bizarre and somewhat admirable artistic leap into the world of avant-garde. Whether his intentions were as such remains cloudy, but The Day the Laughter Died is still a singular experience.