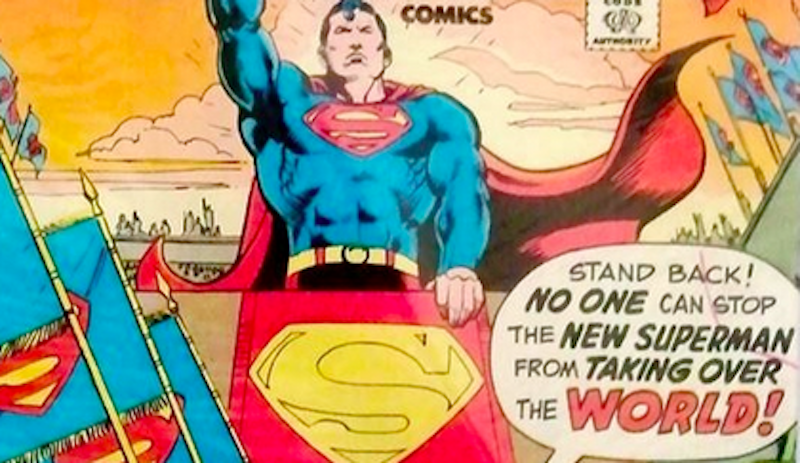

Superheroes conflate goodness with hitting things. For the superhero genre, the best person in the world is the one with the greatest power; beating evil is a matter of hitting it harder. A world in which force and goodness are one and the same and both always triumph is a world in which you're essentially worshipping force—and the worship of force is, as Richard Cooper pointed out last week in Salon, a good thumbnail description of fascism. No surprise, then, to find that early superhero tropes have roots in pro-KKK pulp novels and discourses around eugenics. A fantasy of eugenic superiority and righteous violence can give you Hitler or Superman, either one.

Chris Yogerst at the Atlantic objects to this characterization on the grounds that superheroes are righteous and use their power wisely. Or as he says, "The ‘fascism’ metaphor breaks down pretty quickly when you think about it. Most superheroes defeat an evil power but do not retain any power for themselves. They ensure others’ freedom." But if you were making fascist propaganda, the fascist heroes wouldn't be portrayed as power-hungry whackos. They'd be portrayed as noble and trustworthy. Batman's a good guy, so it's okay that he has all-pervasive surveillance technology in the Nolan films, because we know he'll use it for good ends. Tony Stark is awesome, so when, munitions manufacturer that he is, he makes a super weapon, we know he'll use it well. And all those superheroes can act outside the law and beat people bloody without trial, or even torture them, because they are on the side of good, just like the KKK can operate outside the law in Birth of a Nation because they are on the side of good. (Yogerst also argues that superheroes can't be fascist because they often mistrust the government—as if there's no history of fascist vigilantism, in Germany or here.)

In fact, as Yogerst and Cooper both acknowledge, there's a long history of superhero comics criticizing the superhero genre specifically because of the fascistic way it links the good and the powerful. Back in the 1940s, almost as soon as the superhero genre was created, William Marston and Harry Peter created Wonder Woman as an explicit repudiation of what they saw as a male glorification of violence. Wonder Woman preached peace, and worked to convert her foes in lieu of (or sometimes in addition to) battering them senseless. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen presents superheroes as violent lawless bullies and megalomaniac monsters. The film Chronicle has a teen with superpowers who picks up on the rhetoric of eugenics, with disastrous results. Chris Ware (in Jimmie Corrigan) has a Superman/God figure who acts as a violent ogre/bully; Dan Clowes (in The Death Ray) presents vigilante violence as a kind of adolescent fantasy leading to murderous psychopathy.

On the one hand, you could see the fact that this critique is so prevalent as evidence that it's true; if so many creators over such a long period of time have seen the link between superheroes and fascism, and have questioned the equation of the powerful and the good, then that critique must have some merit. On the other hand, if so many superhero stories warn of the conflation of the powerful and the good, is it really fair to say that superhero comics always promote that particular fascist link? Superhero critique and parody is, and has just about always been, a central part of the superhero genre—so much so that Cooper's essay can be seen not as an attack on the genre, but rather as an example of the genre itself. When he says, "Maybe one day we will get the hero we need: one who challenges rather than reinforces the status quo," you could argue that superhero narratives have been doing that for a long time—and that his essay uses superheroes to do just that.

Superhero stories are about fascism, and the glorification of violence as the good. But being about those things doesn't necessarily always mean they endorse them. Some, like the Nolan Batman films, seem to; others like Chronicle don't; still others, like Iron Man, may go back and forth. Cooper and Yogerst correctly identify the key concerns of the superhero genre, but they both err in suggesting that those concerns have a single meaning. It would be more accurate to say that one thing superhero comics do is think about the relationship between the good and the powerful, sometimes equating them in a fascist way, sometimes criticizing the tendency to equate them, and sometimes examining that equation. The genre is one way we think about fascism—which is, no doubt, why it was so popular in World War II, and why it has had its recent, post-9/11 resurgence.