Once again, as has happened off and on for five decades, Robert Crumb’s the subject of debate. A recent article by Brian Doherty at Reason.com, “Cancel Culture Comes for Counterculture Comics,” suggests that there’s a wave of backlash endangering the legacy of the celebrated underground cartoonist. Anything’s possible. But if Crumb’s reputation really is threatened, I wonder if there isn’t a simpler explanation. Maybe, despite all the ink spilled about Crumb over the years, nobody’s written a really convincing critical analysis of what makes Crumb interesting. Maybe people who aren’t immediately inclined to see value in his work have no real reason to change their mind.

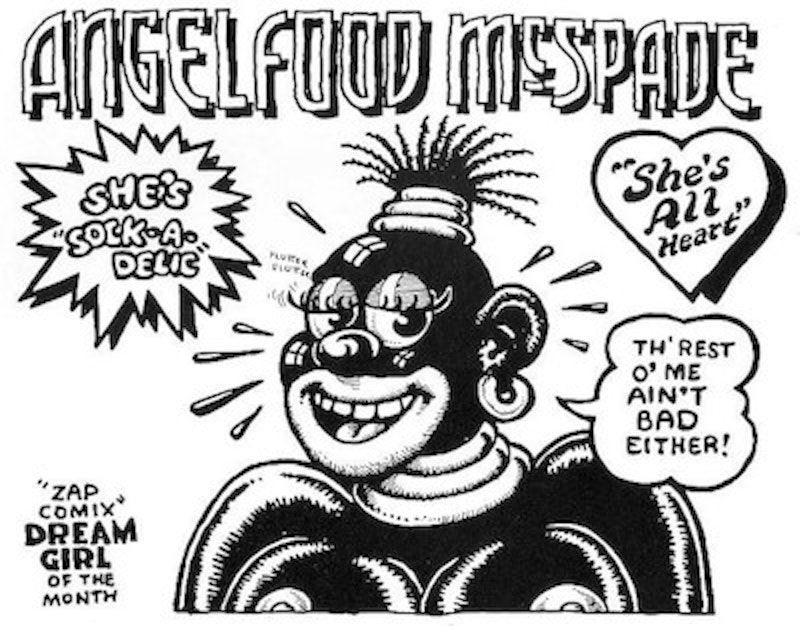

Crumb’s created and published comics since 1968. He started with stories born from his drug trips. Disliking the celebrity this brought him, he began exploring darker terrain including violent sex fantasies and satires that tried to use racist imagery and language ironically. From the start readers found misogyny in his work, along with racism perhaps less ironic than Crumb intended.

It’s not surprising people are turned off from his work. Is there value enough to the comics that a good critic can explain the appeal to somebody who doesn’t care for them at first glance? As someone who always thought Crumb was a mediocre creator, extreme content aside, I’ve never seen anybody manage it.

Let’s start with Doherty’s piece. He notes that half a year ago, cartoonist Ben Passmore made a derogatory reference to Crumb during Passmore’s speech at the presentation of the Small Press Expo’s Ignatz Award, specifically the award for Outstanding Artist. Half a year before that, the Massachusetts Independent Comics Expo took Crumb’s name off one of its exhibitor rooms. Doherty doesn’t say who they renamed it for, but then I can’t find a list of the exhibitor rooms on the MICE site or elsewhere online. Which suggests the names of the rooms aren’t that important.

Doherty observes that Passmore’s comments touched off a brief Twitter controversy. But then, what doesn’t? After observing that publisher C. Spike Trotman tweeted her dislike of Crumb’s use of racist imagery, Doherty cites Jeet Heer “in a post not directly responding to Trotman” at the Hooded Utilitatrian blog saying that the imagery in question was obviously satirical (now shuttered, the blog was run by Splice Today contributor Noah Berlatsky). Heer made that observation in 2011, roughly seven years before Trotman’s Tweet; saying Heer wasn’t “directly responding to Trotman” might therefore be characterized as something of an understatement.

Beyond the renaming of a room, a passing mention in a speech, and a brief Twitter debate, Doherty mentions only one further statement of disapproval—from another cartoonist who, disgusted by an autobiographical depiction of rape in Crumb’s work, states if anyone argues with her about Crumb she’ll show them those panels. That isn’t censorship, but the strong expression of an opinion. Being opposed to people expressing their opinion is an odd position for a libertarian to take, and all of this is a long way from 50 years ago, when, as Doherty observes, people were arrested for selling Crumb’s comics.

Doherty writes at length about the importance of allowing art to depict painful or terrible things, but nobody is arguing otherwise. The criticism of Crumb is twofold: first that as a human being he has done bad things in his life (as proven by his recalling these things in his comics), and second that his work is not actually particularly good. Leaving the first argument aside for the moment, the second argument’s worth investigating.

Doherty tries to counter it with arguments from authority: such-and-such an art critic has praised Crumb, he hangs in galleries and museums, other creators have said he’s important, and so forth. There’s nothing here about individual works, no analysis of what Crumb brings to the medium, no discussion of form. Doherty’s piece comes off as a political argument thinly-disguised as an essay about art, an exercise in using the phrase “cancel culture.” For Doherty, Crumb’s critics have a politicized blindness to an artistic greatness that he thinks should be self-evident and that he doesn’t articulate.

I find the same lack of specificity in a lot of writing about Crumb. His greatness is assumed, not demonstrated. Crumb’s published for over half a century, and people have written about that work for almost as long. I’ve read critical writing about comics for 30 years, and inevitably Crumb’s the subject of a fair portion of that. But I’ve yet to find a piece that establishes what’s valuable in his comics.

I can see a few good points to his work, but nothing that puts him on a plane with, say, George Herriman, Alan Moore, or the Hernandez Brothers. In each of those cases, I could explain in detail what the creator is doing that’s worth looking at, how they handle theme and structure and form and words and pictures. I’m open to reading a similar argument about Crumb, but I haven’t seen one.

I haven’t read everything written about him, of course. And I haven’t read everything the man’s done over half a century. But I’ve read hundreds of comics pages by Crumb, possibly thousands, including satire, adaptation, biography, and autobiography. The range of his work is one positive thing I can say about Crumb. I’ll also happily observe that he’s a skillful illustrator with a good inking line. His panel-to-panel storytelling is effective. His lettering’s clear and distinctive, which is no small thing. He has a reasonably strong visual imagination.

But I don’t think he has a strong grasp of human personality or character. Body language is simplistic and obvious, and the stories lack depth. His satire’s heavy-handed and ineffective. The pacing of his pages isn’t particularly complex. He doesn’t handle theme or subtext well, and lacks a sense of structure or indeed of drama. His worldview’s limited, particularly about gender dynamics and sexual attraction.

Doherty refers in his article to Robert Hughes, who loved Crumb’s work and compared him to Breughel and Gillray. The problem is that Hughes (in the article Doherty quotes) argues that Crumb’s effective because his work refers to shared emotional experiences with the audience. But this says nothing to those who don’t share those emotional experiences and so are unmoved by Crumb. It says only that those who like his work will find his work the sort of thing they like.

For Hughes, the characters of Crumb’s drug fantasies were “figures in a commedia dell'arte that is entirely of our time: we recognize ourselves, our relations with the world, with our lost parents, our present authorities, in them.” But what if we don’t? What if the stories Crumb builds around those characters are too tentative, too vestigial, to carry any significance to us? I wonder if it’s significant that Hughes was primarily an art critic—a critic of individual images, not of narrative forms.

But I wonder if Hughes doesn’t also get at something of Crumb’s appeal. I wonder if some of Crumb’s audience likes his work just because he tells them what they want to hear. Don’t be ashamed of your sex drive, don’t believe in utopia, don’t trust people who say they’re better than you. It’s a message bound to appeal to people increasingly fed up with idealistic kids. Which would explain why critics of Crumb get treated as censors.

I note that R. Fiore, one of Crumb’s more attentive editors, once said in responding to critics of Crumb’s use of racist imagery that “in these holier-than-thou days it’s quite the fashion to declare one’s soul purified of all trace of racism and then conduct witch hunts into the souls of others.” That was in 1995. Almost 25 years later, Doherty’s making the same argument. To look critically at Crumb’s work is implicitly to challenge an ethos of self-indulgence. And if you’re a Crumb fan invested in that self-indulgence you might think that critical approach looks like censorship. You’d be wrong.