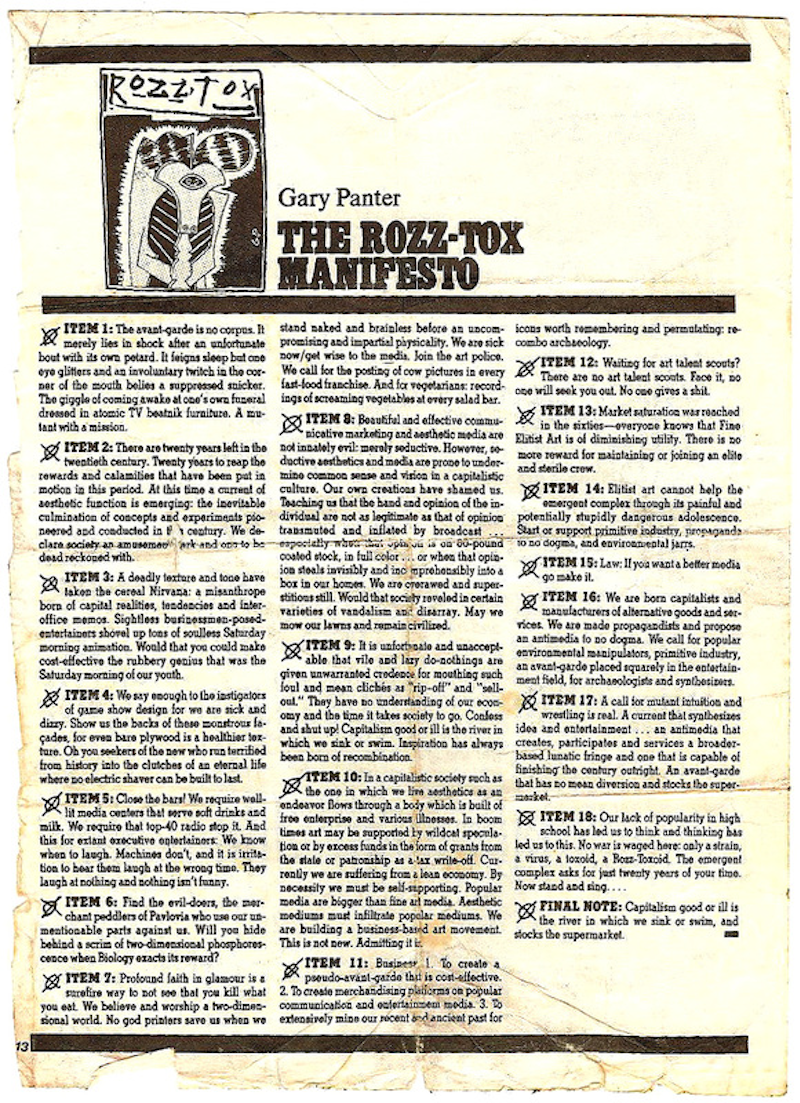

Paul "Pee-wee Herman" Reubens, at 70, took his final bow this week, leaving behind a legacy marked in no small part by the subversive success of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. The CBS Saturday morning phenomenon ran from 1986 to 1991, capturing the imaginations of children and adults alike. Notable for its surreal set designs, courtesy of the famed underground cartoonist Gary Panter (his “Jimbo” is a must-read), the show became a tangible demonstration of what Panter argued for in his Rozz-Tox Manifesto: “An antimedia that creates, participates, and services a broader-based lunatic fringe."

Growing up, I found myself drawn to several such unconventional “children's” shows, thanks to my father's distinct taste for the offbeat. Among them were Fleischer Studios’ Popeye the Sailor (“Vim, Vigor, and Vitaliky” was his all-time favorite episode of anything), Looney Tunes cartoons, The Ren & Stimpy Show, and of course, Pee-wee’s Playhouse. My father had a particular fondness for colorful productions with unusual “built” or “constructed” sets—he’d gladly expatiate on the merits of Michael Powell’s The Thief of Baghdad—and Pee-wee's Playhouse had a similar appeal.

Pee-wee’s Playhouse was not just about storytelling; it was an artistic spectacle. The aesthetics, conceived by Reubens and his talented team, took center stage. As much as my father admired Reubens, he also shared a similar affection for the off-kilter masterpiece that was David Lynch's Twin Peaks, another inexplicable artistic artifact that briefly seized the zeitgeist of its era (and overlapped, during its two-season run on ABC, with the tail end of Pee-wee’s Playhouse’s stretch on CBS).

Reubens curated a remarkable ensemble of performers, including Phil Hartman, John Paragon, Lynne Marie Stewart, Laurence Fishburne, and S. Epatha Merkerson, among others. The creative vision of the show was a collaborative effort by various accomplished artists and musicians, including Panter, Wayne White (a painter and puppeteer who voiced several characters), Danny Elfman (of Oingo Boingo and Tim Burton film-scoring fame), Mark Mothersbaugh (Devo), The Residents, and others. Panter recalled the chaotic first day of production, “Where's the plans? All the carpenters are standing here ready to build everything," the set workers asked. Panter had responded, "You just have to give us 15 minutes to design this thing!" They did, and the result was nothing short of an artistic spectacle. “I was writing an album’s worth of music once a week, and it was really exciting,” added Mothersbaugh.

The sets were a melting pot of styles. As Panter put it, "This was like the hippie dream… It was a show made by artists... We put art history all over the show." It featured Googie-style designs, evoking a psychedelic, over-the-top version of Los Angeles coffee shops. Alongside its artistic richness, the show also employed varied filmmaking techniques, including chroma key, stop-motion animation, and claymation.

My personal connection with the show was so deep that it indirectly led to my homeschooling following a violent conflict with a classmate over his unwise decision to borrow my “Chairry” action figure. Looking back, my obsession with Pee-wee's Playhouse felt like a refuge from the familial discord, a calm in the storm whenever my parents took an interest in my activities.

Despite facing personal and legal challenges, Reubens managed to resurrect his Pee-wee Herman character for Netflix, a testament to the enduring appeal of his creation. It was fine, but the original Pee-wee was sui generis, much like John Kricfalusi's The Ren & Stimpy Show or Chuck Jones' Looney Tunes. Even when their commercial popularity was short-lived due to the unique vision of their creators—as was the case with the Ren & Stimpy and the disgraced, as-yet unredeemed Kricfalusi—their imprint has remained indelible.

In their wake, children's shows have become more refined, their rough edges smoothed out to cater to a wider audience of stay-in-bed adults and indifferent, content-saturated children. SpongeBob Squarepants and Adventure Time are testament to this evolution; both go down easy and amount to almost nothing. Panter's Rozz-Tox Manifesto envisioned a bold future for shows like Pee-wee’s Playhouse and Twin Peaks. However, mainstream media has reshaped this anti-art model to fit the market rather than challenging the market itself, as pioneers like Reubens, Kricfalusi, and Lynch aspired to do. Perhaps Panter should’ve added another item to his list: “In the long run, it’s all content; it’s all product; it’s all grist for the marketing mill.”

Losing Paul Reubens brings a bittersweet reminder of the past, connecting me to the dark corners of my childhood. Predeceased by my eccentric father, Reubens’ departure marks another chapter closed. But in his wake, he leaves a legacy that continues to inspire. In the words of Panter, “If you want a better media, go make it.” And that's exactly what Reubens, Panter, and his other collaborators did. Their run lasted for a half-decade, and then a bunch of people ripped it off, raided it for spare parts. Eminem, of all people, has surely made more money from doing the Pee-wee Herman voice than Reubens.