Comics published in the early-1980s are relics of a medium in transition. The previous decade found the comics scene embracing daring adult-oriented approaches to illustration and writing. They attracted a wider audience of adventurous readers, comic fans, and even patrons of fine art. 1960s DIY zine comics and the underground comix movement laid the groundwork for this demographic change. By the 1980s established creators and publishers were forced to confront a new reality: comics were no longer kids’ stuff or mere squirrel bait for collectors. Nonetheless, fandom’s old guard didn’t vanish the minute issues of Love & Rockets, American Splendor, RAW, and other alternative series sparked the alternative comics explosion.

Some old-school fans resisted the new alternative comics, others embraced them unconditionally, and more were simply overwhelmed by the large influx of offbeat indie titles. Mainstream 80s creators’ work mirrored the varied perspectives as the alternative movement’s aesthetic mutations and progressive ideas trickled into super hero stories. Frank Miller’s Daredevil and Batman: The Dark Knight, Perez & Wolfman’s New Teen Titans, the Chris Claremont/Paul Smith X-Men, and Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing tugged at heartstrings and tackled political issues with a nuance more often associated with their alternative competitors. Marvel Team-Up no. 131 is another extraordinary artifact that displays the collision of disparate ideas so prevalent in mainstream 80s comics.

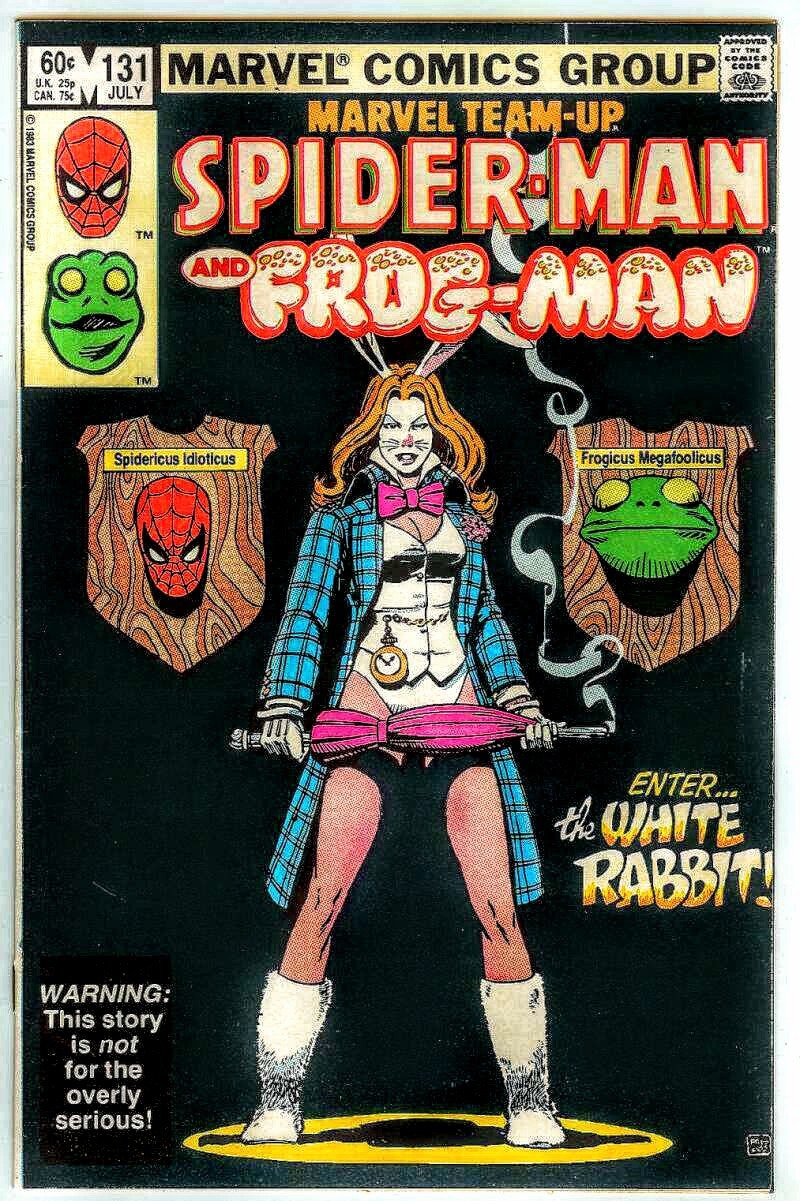

This issue of Marvel Team-Up (MTU) came out a few months before the bizarre Marvel Assistant Editors Month (AEM), the first major Marvel crossover event and an experimental high point in the publisher’s history. MTU 131’s “The Best Things In Life Are Free… But Everything Else Costs Money” is packed with a provocative weirdness that bears traces of AEM-style irreverence (the front cover displays the caveat “Warning: This story is not for the overly serious!”). Though Spider-Man is the star here, “The Best Things…” sports a busy quadrangle of non-Spidey-centric plot threads that never connect until the final pages. Spider-Man/Peter Parker’s ongoing “insecure everyman stuck in a super hero body” saga gets mixed up with the semi-revival of ex-Daredevil villain The Leap Frog aka acrobatic thief Vincent Patilio; the character takes a new name and alignment as a good guy called Frog Man. Standing for the side of law and order, Frog Man’s new alter ego is Leap Frog’s son, the distinctly ungraceful junk food junkie/idealistic comic geek Eugene Patilio.

Just as Frog Man stumbles his way into the crime fighting business, Parker’s downtrodden buddy Roger Hochberg has an emotional breakdown after family dramas and financial hardships spin out of control. And a new super-villain called White Rabbit has hit town. This sexy/proto-furry is the alter ego of shallow heiress Lorina Dodson. Unchecked privilege and psychotic obsessions with classic literature shatter her moral compass and drive her to a recreational life of crime, robbing fast-food restaurants and other modest establishments. Naming and modeling herself after a character from the novels of Lewis Carroll, the buxom/thrill robbing heiress looks a lot like a Playboy bunny and commits crimes while shooting carrot-shaped razors from a gun disguised as an umbrella. She’s clad in a leotard, whiskers, and white face paint; a top hat, jaunty vest, and pocket watch complete the outfit (a homage to Alice In Wonderland‘s Mad Hatter). Supported by a sketchy bunch of freelance thugs, White Rabbit throws money and crackpot schemes around with abandon.

This is an archetypal 80s villain—rich, self-centered, and dangerously negligent. She’s a satirical/yuppie bashing caricature of what happens when a spoiled brat grows up. The story’s writer, J.M. DeMatteis, is well-known for challenging scripts inspired by moral and philosophical concerns; his White Rabbit characterization is an odd union of anti-capitalism and male gazing. Artists Kerry Gammill and Spider-Man vet Mike Esposito draw her in a style that never strays far outside the curvy lines of conventional sex appeal, reinforcing a double-edged eroticism. The art gives the villainess undeniable beauty, but this touch is mainly employed to contrast her ugly negligence.

Inevitably Spidey and Frog Man battle against White Rabbit, but their clash is cut short by Roger Hochberg, who derails everything once MTU 131 heads into its final act. Exactly how Hochberg stops the battle can’t be described in reductive terms. It’s a twist loaded with symbolism and a clear reference to the focus on reality that was intrinsic to many 80s alternative comics— a low-key character who hasn’t a single super power, one who has a barely tenuous role in this outlandish story ends up at the center of its climax. Over-the-top criminal arrogance and heroic determination are kicked to the curb as an earthy concern for family safety inspires the tale’s most decisive act of bravery.