Billy Graham died recently, but not the Billy Graham who meant anything to me and not the one I thought would die first. No, the original Billy Graham, even with a 25-year head start, seemed likely to outlive Wayne Coleman, the multi-sport washout who took the evangelist’s name as his own because he once fancied himself fueled by the same religious fervor. Coleman—the so-called “Superstar” Billy Graham—has survived all the possible failures a man could face: career failure, liver failure, heart failure.

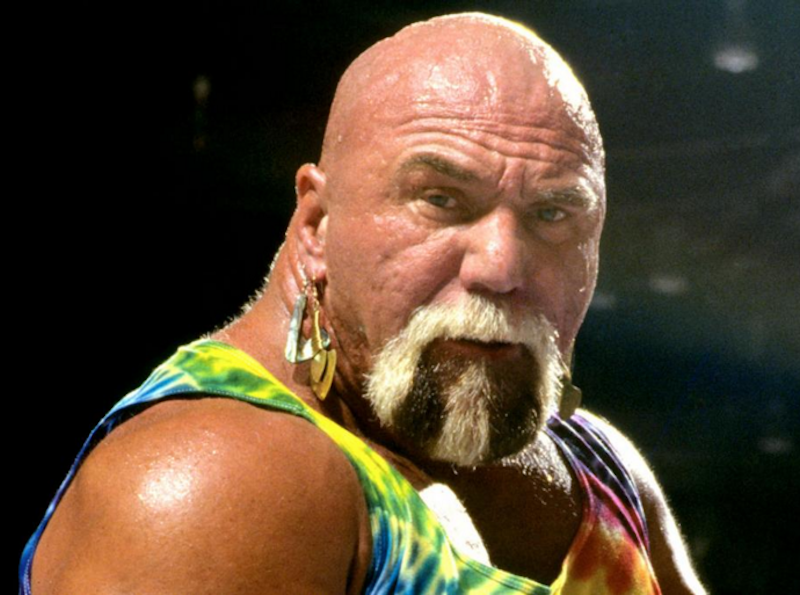

When I first saw the Superstar on the old Jim Crockett Promotions shows, the “Superstar on the TBS Superstation” as he would jive-talk during his interviews, I was transfixed. He was a bald, muscular, and weirdly-bearded character who dressed like a hippie and spoke like an African-American. His monologues always devolved into rambling, rhyming delusions of grandeur, with him reminding us that he was the “man with the biggest arms and the man who could do the most harm” and that he “ate t-bone steaks and lifted barbell plates.”

There was nothing quite like this routine, not even with Dusty Rhodes and Roddy Piper making the rhetorical rounds, because the Superstar was something special: he was the original, the innovator, the genuine article, the man everybody ripped off. He pioneered the bleached-blond hair, the tie-dyed t-shirts, the earnest co-opting of Muhammad Ali’s speech patterns (which in turn had been derived, at least in part, from young Cassius Clay’s thorough study of wrestler and early TV star “Gorgeous” George Wagner). His most slavish imitators, men such as Hulk Hogan and Jesse Ventura, would purloin his aesthetics and go on to achieve great renown.

But the Superstar always came up short. By the time I first laid eyes on him, he’d washed out of professional boxing (his first and only match lasted a round and ended with him knocked out), door-to-door evangelism, professional football (he signed contracts with a host of NFL and CFL teams impressed by his unique blend of size and speed, then injured himself during training camps), powerlifting (where he managed to achieve a 605-pound unequipped bench press), bodybuilding (he won “biggest arms” at a major show), and, most damning of all, the WWE.

The WWE run broke him, Superstar claims in his WWE-approved autobiography Tangled Ropes, because even though he had become that promotion’s most popular bad guy world champion, he was ordered after nine months on top to lose the belt to freckle-faced amateur wrestling star Bob Backlund. Superstar, a temperamental man who depended on amphetamines, painkillers, and massive doses of steroids to keep his body in good working order, went off the rails. He knew he had achieved something great, with his stream-of-consciousness interviews and tape-measure biceps, but the elder Vince McMahon was too stuck in his ways to acknowledge it. Decades before the younger Vince McMahon would ride wrestling bad guys Steve Austin and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson to megabucks, Superstar had demonstrated that the fans would pop for a charismatic bad guy.

But time is neutral, and Superstar was a man who always peaked too soon and for far too short a period. I recently interviewed bodybuilding and powerlifting legend Stan Efferding, a seemingly indestructible athlete who continued to set powerlifting records well into his 40s, and Efferding discussed how anyone relying on anabolic steroids and exogenous testosterone to maintain bodily homeostasis was doomed to failure unless everything else—diet, exercise, sleep, hygiene—was right on the money. In the case of the Superstar, a delusional addict with a voracious appetite for pills and syringes, nothing was ever right on the money: he could bench-press 605 pounds with no warm-up one day, tear his pec the next, slip into a bedridden state for months, then re-emerge from his cocoon to perform one more feat of derring-do before developing pneumonia. He was always winging it, whether in boxing or wrestling or football, and hoping that he might parlay a few fleeting instances of greatness into something that wouldn’t end in abject failure.

The Superstar’s last real chance for one more shining moment came at the 1980 World’s Strongest Man contest. That competition was still in its infancy, and even though men like Bruce Wilhelm, Don Reinhoudt, and Bill Kazmaier had emerged as leading contenders and somewhat specialized athletes, it was still a sort of all-comers invitational featuring loads of pro footballers, armwrestlers, pro wrestlers, bodybuilders, and performers from other strength sports. Superstar, who’d been many of those things himself, figured his odds were as good as anyone’s. After all, Olympic weightlifting champion and fellow wrestler Ken Patera had finished a close third in the inaugural competition.

“I thought the World’s Strongest Man contest might help me turn the corner,” he explains in Tangled Ropes. “And despite my wife’s protests, I sold our furniture to subsidize my training, which was highlighted by taking as many steroids as I could obtain and drinking three gallons of raw milk every day.” This wouldn’t be the last time that Superstar, flat broke and at the end of his noose, dug into his reserves to subsidize the prodigious consumption of drugs needed to power his comeback. But this would prove the last time that his body could even partially withstand the tremendous strain.

The 1980 World’s Strongest Man contest, from the perspective of someone who’s watched all of them, wasn’t particularly compelling or dramatic. Bill Kazmaier dominated the events in workmanlike fashion—Superstar claimed in a recent interview that Kazmaier was likely blood-doping, as well as gulping down the bottlefuls of Dianabol that everyone else was—and the rest of the field just muddled through. Six-hundred pound armwrestler Cleve Dean, a holdover from a previous competition, proved capable of pulling a truck and not much else. Lars Hedlund and Geoff Capes, athletes who had a solid grounding in strongman fundamentals, held their own.

But Superstar was the one to watch, explaining that he became the “sentimental favorite” after pulling a hamstring during the log lift. Such pulls and tears were constant problems for athletes who gobbled down steroids in the era before human growth hormone was readily available, particularly athletes like Superstar who trained on a kind of feast-or-famine basis and never developed the tendon and ligament strength needed to bear the strain of the 330 pounds he was now packing onto his 6’4” frame.

For the most part, Superstar did okay. He did well in the battery lift and bar bend and terrible in almost anything that involved core or lower-body strength, eventually finishing seventh overall. As I watched, I empathized with his plight: because I entered strongman from a bench press and deadlift background, the log lifts and other overhead movements involved in the sport had bedeviled me during my first two competitions (I pulled the same calf muscle at both events). But Superstar’s performances didn’t really matter, because he received a lot of interview time and there engaged in his usual theatrical tirades. He later admitted to considering “getting color” during the log lift event, having proven himself an excellent bleeder during a legendary series of matches with Dusty Rhodes, but thought the better of it after struggling to actually hoist the log.

For his trouble, Superstar received $3,350, or slightly less than he had made from selling all of his belongings to prepare for the event. This last go-round on a heavy-duty steroid regimen further compromised his health, and by the time I first encountered him during the mid-1980s, his wrestling repertoire was limited to kicks, punches, and very safe, slow bumps. He could barely perform his signature hold, a bearhug in which he hoisted his opponent off the ground, and when he did attempt it, he kept it on for only a few seconds. By the time he had left Jim Crockett Promotions and reappeared in all his tie-dyed glory in the WWE, his body was so brittle that he wound up requiring surgery on his ankles, hips, and knees after only a handful of matches against “Hacksaw” Butch Reed.

It was interesting to watch the Superstar fail during his last run in the WWE, because it was clear to me even then that Vince McMahon, Jr. admired the hell out of the guy. Yet Superstar was also a drug addict, a man who was always falling apart and coming back, and his receding years have been marked by numerous heel turns: he tried to destroy McMahon’s steroid-fueled wrestling business by cooperating with federal investigators, he made nice with McMahon so he could be inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame and earn a few bucks selling his WWE-approved book (which is a fun and breezy read, filled with loads of self-loathing and self-delusion), and eventually hocked his WWE Hall of Fame ring to help pay mounting medical bills before embarking on another round of shoot interviews criticizing McMahon and many of his co-workers.

In that last respect, Superstar occupies a privileged position. He and WWE contemporary “Honky Tonk Man” Wayne Farris have spent the past 30 years of their lives recording interviews about their wrestling days, easily producing more combined hours of oral history than any other pair of wrestlers who have ever lived. In Farris’ case, the stories are venom-laced but the teller is still in possession of his faculties; his accounts might be inaccurate, but they’re intended to put him over and sell whatever version of himself he’s currently peddling on the open market for wrestling appearances. Superstar, meanwhile, speaks without regard for truth or falsity. The few great things he actually accomplished are always leavened with outright lies or favorable misremebrances. Even in Tangled Ropes, the cover-to-cover authoritative memoir of his life to the point of its publication, he’s frequently wrong.

“I came in fifth in a field of ten at the World’s Strongest Man,” he writes. “Not bad, considering my injury.” As noted earlier, he finished seventh, an easily verifiable fact. Then again, who gives a fig about the truth if it gets in the way of a too-good-to-be-true story about a world-beating failure?