Norman Scott didn’t have a big moment of triumph on the witness stand. The TV version of his story claims otherwise and shows him scoring like a pro. If only. The series, A Very English Scandal (on Amazon Prime), takes as its source a book of the same name and that book torpedoes the idea. Scott the witness didn’t give a speech, but he did admit to telling the occasional tall tale and accepting media payments for his accusations. “The damage was done,” writes John Preston in his capably told, and to some extent wise and witty, true-life account of how a prominent British politician plotted the greasing of an ex-boyfriend. The ex-boyfriend was Scott, a floundering beauty who’d become a long-running pain in the neck. The politician was Jeremy Thorpe, leader of Britain’s third-place Liberal Party and a man missing the valve that regulates self-involvement.

Thorpe inhabited the spotlight during the 1960s and 70s, a period when successive flop governments inspired some voter giddiness about party choice. As the TV show reminds us, he frequently spoke up for black rights. Despite that, he was a stinker. “It’s no worse than shooting a sick dog,” Thorpe said when he wanted Scott killed, or so testified Thorpe’s closest ally in the Liberal Party. Sexual relations with his intended murder victim had begun when Scott, 20, showed up in London without a job, a home, a university degree, or a National Health card; no card meant no hope of legal employment. Thorpe, sensing opportunity, mounted the boy and did so many more times in the next few years. Trouble eventually followed, and followed, until the whole story wound up in the newspapers, after which Thorpe stood trial for his ex-flame’s attempted murder. The trial ended with the defendant walking free—into political oblivion, but free. Scott tried to tell his story, but judge and courtroom found his account null.

On Amazon Prime we see a shameless rendition of the court proceedings. Scott’s badgered about taking money for TV appearances. “I don’t care about the money,” he flares. “But I do care how men like me are shoved into corners and masturbated in the dark and then thrown out the door like we’re dirt. Like we’re nothing, like we don’t exist, and all the history books get written with men like me missing. So yes, I will talk, I will be heard and I will be seen, your honor. You can pay me or not pay me, I don’t care. But the one thing you will not do is shut me up.”

Next he’s clattering down a courthouse staircase, recapping for buddies. “I was rude, I was vile, I was queer, I was myself,” he tells them. Outside, on the courthouse steps, Scott addresses a crowd of reporters. “It went very, very well indeed,” he says. In real life there was no speech and no cheers. The TV version’s an improvement: we want to see Scott do well, and if a gay man’s going to triumph, it ought to be through letting his true self out and making noise about it. As Scott informs us, that’s what he’s doing here. But today’s cliches didn’t make the rules in Scott’s court room. Back in 1979 he got nowhere.

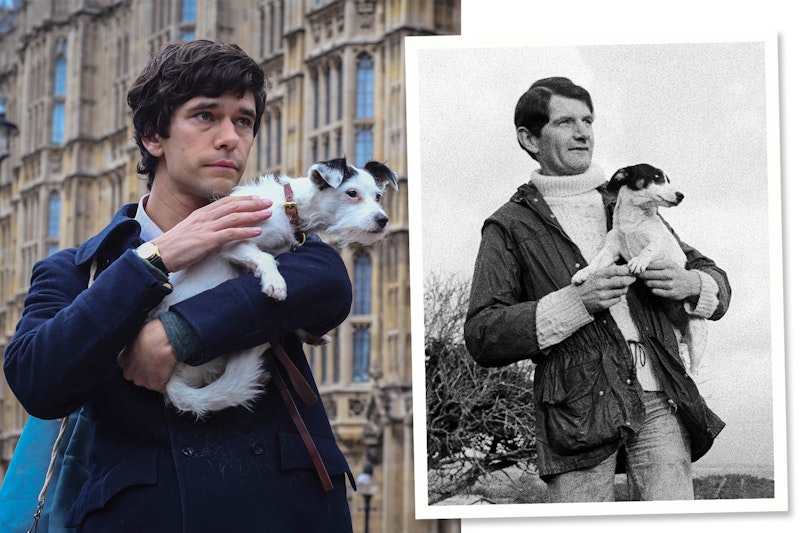

A Very English Scandal stars Hugh Grant as Thorpe and Ben Whishaw as Scott. They’re good, everyone’s good; it’s well-made British TV. The lighting’s murky and the kick-off episode has dialogue sometimes too fleet and nimble for a foreigner’s understanding. But when the show wants to make a point, it goes right ahead. For Scott’s post-testimony triumph, a hetero schmuck is on hand merely to tag along. There’s a loud blowsy old gal hanging on Scott’s left arm, and a youngish but not too striking gal on Scott’s right arm. The old gal supplies noise and comedy relief; the youngish gal shows that there are normal-looking people who know Scott and care about him (he’s had quite a career, emotionally). She has a grinning, supportive husband, and he comes trucking up behind them as the trio turns a corner. Normally you look ahead when trying to catch up; the man doesn’t. His eyes are down and he speeds around the corner as if expelled from a device. He’s a small man, demure of dress, and his lips are set. He doesn’t grin until he’s right behind Norman’s shoulder, and then you don’t really see his face, just slivers of it as Norman’s head and shoulders move.

The grin, pretty much by itself, is there in our sight and then the two seconds are done and the man’s ducking mysteriously to the left. He's supplied one more bit of applause, visual but applause, for the hero’s self-congratulations. I suppose he also shows how the balance can go when your demographic isn’t the one in charge.