I’ve few illusions about The New York Times’ political agenda—although not enough attention is given to the “Heed what we say, not what our company does” hypocrisy—and haven’t since I was a youngster reading the paper in the 1960s. The Times’ political and social views, though usually not my own, are still valuable for anyone trying to make sense, especially in the Trump Era, of the country’s ongoing polarization, even if today’s iteration, while deafening because of social media, is more bark than bite compared to more tumultuous decades.

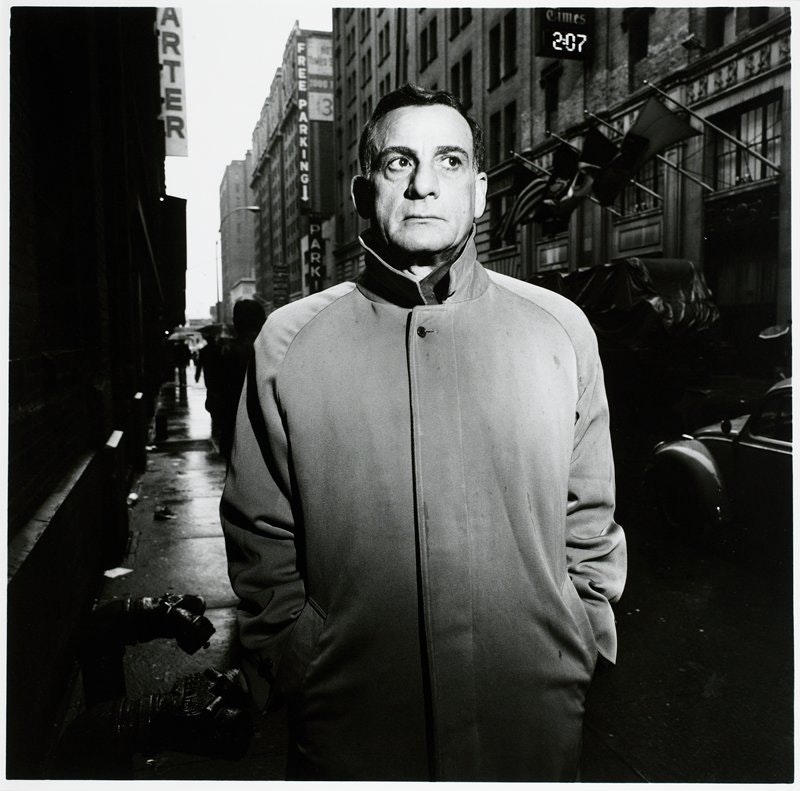

Nevertheless, I took umbrage at an October 25th obituary of onetime New York special prosecutor Maurice Nadjari, who passed away last month at the age of 95. I understand that some obits of men and women who’ve at some point in their lives gained notoriety can be a struggle for an honest writer: Nadjari was, for a relatively brief period, a controversial figure, and any account of his long life is correct to point that out. However, Robert D. McFadden’s obituary read more like one more hit-job on Nadjari, portraying him as a proto-Rudy Giuliani, even though he’s been out of the spotlight for decades.

As is typical with entitled New York Times writers—and journalists in general—McFadden is condescending when he writes that Nadjari was popular with “ordinary New Yorkers” (the rabble), while the powerful in New York railed against him as a “grand inquisitor.”

The fourth paragraph sums up the arc of McFadden’s lengthy (at least in these days of shrinking copy inches): “To his detractors, many in law-enforcement and among civil libertarians, he was a grand inquisitor who used illegal wiretaps, entrapment scams, unsupported allegations and leaks to the press in a ruthless, messianic pursuit of villainy that destroyed reputations and innocent lives.” Tellingly, McFadden, 82, quoted not a single person to back up that incendiary paragraph. It’s true that many of the key players during Nadjari’s run are now deceased, but surely there are current legal scholars and historians who could’ve either confirmed or rebutted McFadden’s uncorroborated assertions.

At this point, Nadjari’s career is, if not a footnote, mostly forgotten to history—he wasn’t a reviled dictator, terrorist, convicted criminal or infamous politician. We’re not talking J. Edgar Hoover, Richard Speck or Al Capone here.

I am not unbiased, for I knew Maury Nadjari very well as a teenager and young man. That, admittedly, leads to a more personal view of the man, but also sheds light on the shoddy coverage of newsmakers. One of Nadjari’s two sons, Howard (or Howie as I’ve always known him) is one of my dearest friends; in Huntington, New York we went to junior high school, high school and then Johns Hopkins University together. I was a regular fixture at the Nadjari household on LaRue Dr. in the late-1960s and early-1970s, and found Howie’s parents, Maury and his wife of 69 years, Joan, warm and generous people.

I wouldn’t say Maury (oddly, at least for that era, Howie and his brother Doug referred to their parents as “Maury” and “Joan” rather than mom and dad) was a cream puff who turned off his pronounced political views when he returned home at night. I doubt he cared for my long hair, hippie lifestyle and championship of politicians like Gene McCarthy and George McGovern, but he never let on. Needless to say, I remained mute when the topic turned to marijuana, the possession of which he believed was a real crime.

We’d engage in debate, and though I flatter myself by believing he thought I was a worthy adversary (if young), once the discussion was wrapped up we’d converse about any number of less controversial topics, often while having dinner. Joan would chime in with her thoughts, as would Howie and Doug, and it almost always made for a convivial afternoon/evening/weekend day. At some point, when the Atkins Diet captured the nation’s imagination, Maury embraced it (even though he was always very fit, and rarely missed an early-evening swim at one of Huntington’s public beaches), saying to me one night, “Steak and lobster! What could be better!” My memory might be fucking around, but I’d swear he pronounced it “lobstah,” in a New York accent.

When my father suddenly died in 1972, Joan and Maury were very comforting (as were the parents of my friends Elena Seibert and Bobby Ringler), an act of kindness that was from the heart and not some unfeeling “messianic” narcissist. Both the Nadjari parents wrote separate, and not pro forma, letters to my mother, for which she was very grateful.

I hadn’t seen Maury and Joan in years, though Howie, in our semi-regular correspondence and birthday phone calls, filled me in. A few years ago I wrote a story about Joan, in which I theorized that she was a woman ahead of her time, a pre-wave feminist. Not long after, she wrote me a hand-written 10-page letter that was filled with small jokes (and she was nearing 90 at the time), but dashed my view of her as a trailblazer, saying she was very happy as the wife of the man she loved, and taking care of the kids.

Back to the mean-spirited obituary. McFadden apparently doesn’t realize that the war against Maurice Nadjari is over, and has been for a long time.

•••

A few brief notes on Bob Dylan’s Travelin’ Thru, Volume 15 of his “bootleg” series, this one covering the period of 1967-1969. It’s a three-disc set (unlike those that covered his 1965-66 magic carpet ride or the Rolling Thunder concerts), mostly because he recorded John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline so quickly. The outtakes from JWH aren’t much different from the released album, although “As I Went Out One Morning” is sung like a dirge, unlike the cryptic gem that made the final cut.

The duets with Johnny Cash are mostly great (although the sound quality not much better than a boot of the sessions I’ve had for years), and “I Still Miss Someone” and “Guess Things Happen That Way,” Cash hits from 1958, stand out. I’d never heard “Wanted Man,” a song Dylan wrote and gave to Cash (and never released himself), and though the lyrics are kind of tossed-off, probably written in 10 minutes, it would’ve been a fit on Nashville Skyline or Self Portrait.

Also included is Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away,” which he taped for Cash’s premiere episode (June 7th, 1969) of The Johnny Cash Show, which lasted two years. I remember watching; it was the first time I’d seen Dylan sing on TV, and, because he was purposely in exile, it was dramatic when Cash simply said, “Ladies and gentlemen, here’s Bob Dylan.” It’s still a stirring performance.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955