A lady in Southern California was once caught emailing a Photoshopped picture of President Obama as a chimp, a baby chimp with a chimp mom and dad (“Now you know why—No birth certificate!”). The lady was an official with the Republican Party of Orange County, so her forwarding of the email attracted attention. In the small media flurry that followed, she emerged as a grandmotherly type who was baffled by the issue at hand. She understood that people thought she had something against blacks. But why did they think that? The charge hurt her.

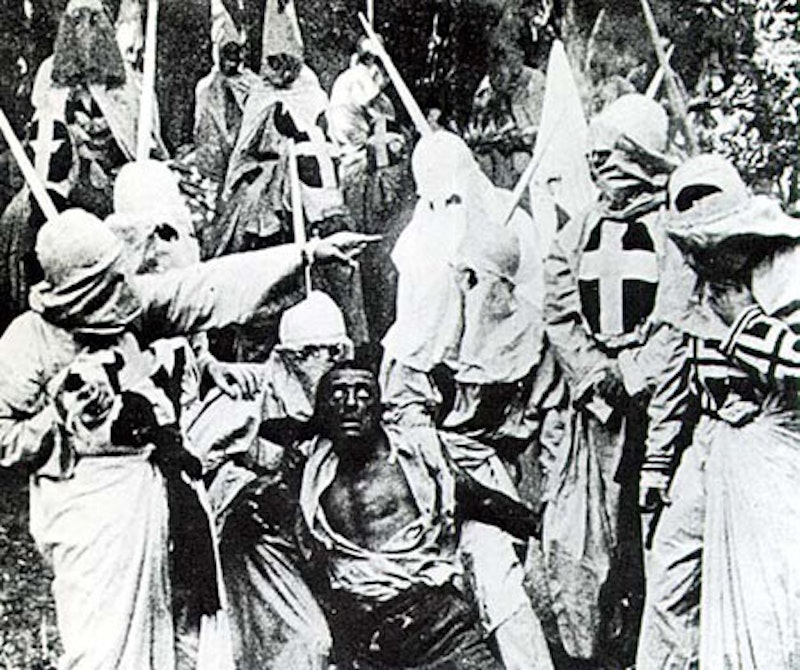

She and D.W. Griffith have something in common. Griffith is the man who made The Birth of a Nation, the Jaws or Gone With the Wind of the first Hollywood generation. The movie is about the Ku Klux Klan, specifically the Klan’s founding and its victory over the newly liberated blacks of the South. When the hero music plays behind someone on a horse, the someone has a Klan outfit. He is sicced on a black, and the black gets stomped back into place.

Birth made $10 million, which today would be about $227 million. It was Hollywood’s biggest hit for three decades. That makes it a sort of founding document for America’s movie business, with the letterhead showing a Klansman on a horse. But even in 1915 there was opposition. A Klan blockbuster could get made back then, but it did face a measure of trouble.

The star of the film, Lillian Gish, wrote about the backlash in her autobiography. She published the book in 1969, generations after the event, but she was still appalled. The film had been “assailed,” she wrote. “From the beginning, Birth of a Nation encountered extraordinary censorship and protests, as well as praise.” It was attacked by “important liberals” for “alleged prejudice and race baiting.”

On balance Gish thought the controversy helped the movie. If the NAACP was against something, people wanted to see it. News of violence helped too: “Fist fights and picket lines occurred at many premieres of the film… War news in the papers gave way to stories of this violence. Cities all over the country clamored to see the film.”

Even so, the response hurt. “Mr. Griffith reacted to the violence and censorship with astonishment, shock, and sorrow,” Gish wrote. And out of all the attacks, “the one from which Mr. Griffith suffered the most was the accusation that he was against Negroes.”

The director’s reaction “slowly turned to anger.” Griffith became a militant on behalf of his film. He argued its accuracy, pointing to legislative records and high court documents. He issued a pamphlet about free speech, showed up at court hearings and legislative hearings. His film’s viewpoint? “He admitted freely that it was a Southern point of view,” Gish wrote. But, as she and Griffith saw things, that didn’t mean the movie was against blacks: “of an attack on race or on the Negro race as such, Mr. Griffith insisted, there is no hint, no scene or sign.”

Gish wrote, “Griffith was incapable of prejudice against any group.” She remembered fondly that he “always treated Negroes with great affection, and they in turn loved him. Being a Southerner, he could communicate with them, and they liked to be around him because he was amusing. When some of them turned against him after the showing of The Birth, he was deeply wounded.” Hating blacks would be like hating children, Griffith thought.

In the midst of her account, Gish included a public statement by Thomas Dixon Jr., the writer whose works Griffith turned into Birth. Dixon attested that the film had been inspected and approved by a panel of three clergymen—one Universalist, one Presbyterian, and one Roman Catholic. The clergymen found the film had six effects on the audience, all of them good. The first was “It unites in common sympathy and love all sections of our country.” The third was “It tends to prevent the lowering of the standard of our citizenship by its mixture with Negro blood.”

By “all sections of our country,” Dixon no doubt meant North and South, but the emphasis on “common sympathy and love” is still quite a note next to the remark on blood admixture. Dixon’s wind-up remarks are also interesting. “I am not attacking the Negro of today,” he wrote, and he counted blacks in his story: three good ones (“faithful unto death”) and two bad ones.

Back to Gish. Finishing her defense of Griffith, she wrote that the director “believed that the Negro had made great strides since the end of slavery… He said that the white man had taken centuries to attain the intellectual and spiritual powers that many Negro citizens had achieved in a few decades.” Which would mean that, to his mind, it was remarkable for blacks to read, write, tie ties, and so on. It would also mean that he thought blacks in 1865 were backward and possibly at the level of animals, just as they were shown in Birth of a Nation. But that’s the point. He wasn’t repudiating Birth. He just couldn’t see why anyone thought he was against blacks.

It’s amazing how some reflexes stay in place. Since Birth of a Nation, out-in-the-open race propaganda on behalf of whites has gone to the margins. Instead of giant film premieres, the material gets treated to Reply and Forward. But it’s still there, and the people behind it are still likely to come out with the same thing as in 1915: Who me?

And they’ll mean it.

Let's Say You Made A Blockbuster Movie About Kicking Ex-Slave Ass

You’d still think you weren’t a racist.