Diana Mosley told World War II this way: Look at what Churchill allowed Russia to do to Poland. No mention of how Russia came to be in a situation to do it, or why Churchill was in no situation to stop Russia. No mention of Germany or Hitler. I like the breeziness. H.P. Lovecraft said if people connected the dots, the human race would go crazy. Lady Mosley didn’t connect dots. Reading a collection of her writing, one sees an intelligent, lively, largely tolerant, rather charming mentality fluttering hard atop the stink of its loyalties and official beliefs. She was a Nazi lover and a fascist; she stayed that way forever. But she opposed preventive detention. In 1940 the British had to clear the decks; Lady Mosley and her husband were thrown in prison and didn’t see each other until war’s end. Later she wrote again and again about the unfairness of their case, and about the need for habeas corpus. She didn’t say how fascism and habeas corpus were supposed to get along. She did write some detailed and moving passages about her fellow inmates in women’s prison.

A moment I liked: somewhere in the collection she remarks that we all have our pleasures, hers is to read Saint-Simon in French, others may prefer skittles or color supplements, what does it matter. A fellow-creaturely remark, if you like.

The book is The Pursuit of Laughter: The Most Controversial Mitford Sister. This Mitford was so controversial because she was a Mosley, the wife of the man who led fascism in Britain when the Nazis looked ready to take over. But the publishers chose high spirits. On the cover a long-throated person cocks her head at life and its nonsense; she’s drawn period-style. Inside lie Hitler (he does show up, because she remembers he was fun at parties, a gifted mimic) and Stalin and Duff Cooper and her prison diary, and World War II as seen by an Englishwoman favorable to Nazis.

A famous man died, an Englishman in America. One day his son stopped by his grave to pay respects. Another young man was there and the two fell into conversation. The second boy told the first how much he admired the dead man, how he had read everything about him and everything by him. The man’s son replied, “Oh yes? Well, he was my father,” or words to that effect. Years later he wrote a column about the incident and kicked himself for those words. He didn’t say what about his answer had been so dreadful. I’ll fill it in: he was one-upping the boy. In effect the statement read “He was my dad, you lose.” To my mind the statement could’ve meant “He was my dad, isn’t that something?” Hence I need to process before deciding insult was intended. I say the hitch isn’t me being slow; it’s British thinking versus American.

The man was Kenneth Tynan, a name inserted down here because the son’s column can’t be found. No, Google turns up nothing. All I have is my memory, a few paragraphs read long ago. In the Guardian, or so I thought. I don’t want to stick Tynan’s name atop that. Let him be a footnote, one accompanied by a confession of poor sourcing. And let his connection to the above anecdote be suggested, not affirmed. This leaves my little proof, my petite incident highlighting English ways versus American, stranded on admittedly vaporous ground. I accept that. Its truth lives and will find further form.

My joke about the English playwright who’s gone sellout in Hollywood. The playwright refers to his agent as Hobbes because “he’s nasty, brutish, and short.” Follow-up to joke: some smart guy voices the obvious rejoinder. The playwright answers, “No, sir, that is I. I am solitary and poor!”

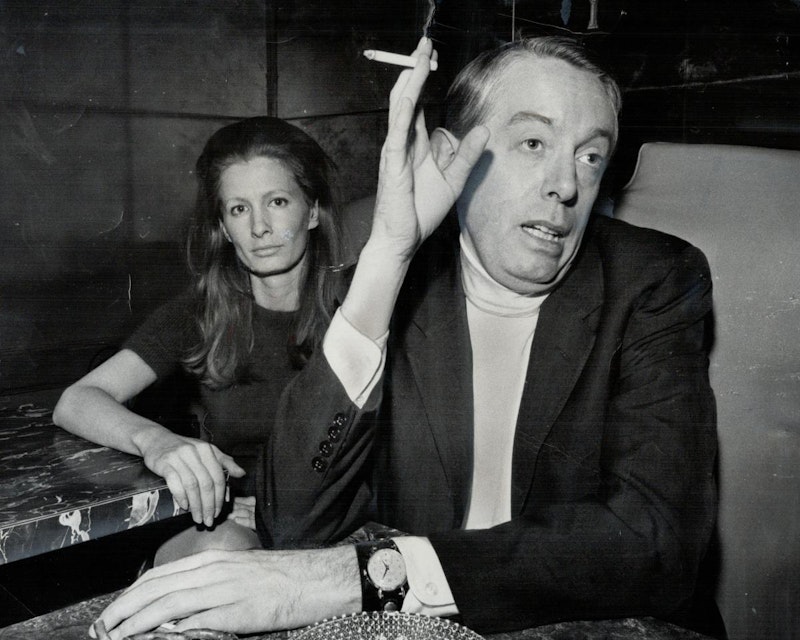

*Lady Fascist, snooty kid. Tainted breeze, British decline. Found on a poster in 1977, with porny drawings and East London showtimes. An aggressively canopied bed features in the poster art.