Jann Wenner is a sociopath. That’s the conclusion any reader will reach about 50 pages into Joe Hagan’s Sticky Fingers, a new biography of the Rolling Stone founder and editor. It’s a remarkable book, a bio with the full participation of its subject, an egomaniac so delusional that he only denounced it once it was finished. According to Hagan, “It was all on the table—there’s nothing he didn’t know… He’s used to having control, and that’s a difficult thing.” Wenner cooperated with Hagan for four years, told him everything, and it was only this past June, when he read the finished manuscript, that Wenner realized how poorly he comes off: “I gave Joe time and access in the hope he would write a nuanced portrait about my life and the culture Rolling Stone chronicled… Rock and roll set me and my generation free musically, socially and politically. My hope was that this book would provide a record for future generations of that extraordinary time. Instead, he produced something deeply flawed and tawdry, rather than substantial.”

Wenner’s stunning lack of self-awareness and a self-esteem so strong it occludes everything but “marble busts” and monuments is a thread that runs throughout Sticky Fingers, 547 pages of dirt on one of the most important publishers and media figures of the 20th century.

So what could Wenner possibly object to? Well, there’s the binge-drinking, the piles of cocaine, the staffers he never paid, the partners he ripped off, the friends he never had, the ideas he stole… but when Wenner says the book is “tawdry,” there’s no doubt in my mind that he’s referring to the many pages devoted to his ambiguous homosexuality and his marriage of convenience and business to Jane Wenner (who goes full Howard Hughes in the 1970s and '80s, holed up in the couple’s Manhattan apartment stoned on Quaaludes and unable to leave her bed for days at a time).

Wenner’s homosexuality and the intense shame he felt are discussed throughout the book, from his days as a schoolboy through the AIDS epidemic in the '80s. Pressed on it, Wenner insists, “It just wasn’t my worry, because I didn’t live that lifestyle. I was a part of the straight world. Still am to this day.” His colleagues call bullshit. Seymour Stein: “He’s lying to you. He was frightened by it. We all fucking were.” Kent Brownridge saw “fear in his eyes” whenever AIDS came up. His own wife admits: “We were all worried about AIDS.”

This isn’t some thinly-sourced Albert Goldman-esque hit job. Hagan interviewed dozens and dozens of rock stars, celebrities, former Rolling Stone employees, industry moguls, and people that were around Wenner and the magazine. A brief list, just to establish this book’s credibility: Annie Leibovitz, Greil Marcus, Yoko Ono, David Geffen, Bob Dylan, Bono, Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Jerry Hopkins, Dave Marsh, Jon Landau, and Cameron Crowe (an incomplete list, obviously not including any of the dead who were quoted). A remarkably consistent portrait of Wenner emerges from these interviews: a shallow, narcissistic, gluttonous, hapless buffoon. This is reiterated throughout the book, whether it’s Wenner foolishly publishing a book of John Lennon’s legendary 1970 Rolling Stone interview against Lennon’s wishes—ruining a friendship that would never be restored—or buying a $6 million private plane because he suddenly felt like skiing in Aspen one afternoon. “I would just circle over LaGuardia to have lunch.” What kind of maniac says something like that to their biographer and expects a blowjob in return?

Wenner’s cooperation and subsequent complaints make Sticky Fingers a uniquely compelling and authoritative biography. Whenever you hear a subject doesn’t like a book about them, you know it’s going to be juicy, but without cooperation of first, second, or even third parties means most of the dirt one gets out of it is apocryphal or naked fiction. Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon is a really fun and dark book, but I don’t trust it as record, mostly as curio. Goldman is an example where the biographer’s own hang-ups and obsessions come out so blatantly one questions the author and their editors’ lack of self-awareness. Goldman was obsessed with proving that John Lennon was gay, and the way he writes about male performers is… suspicious. At least Wenner’s latent homosexuality didn’t wither and fester into homophobia—all things considered, he should consider this book a success.

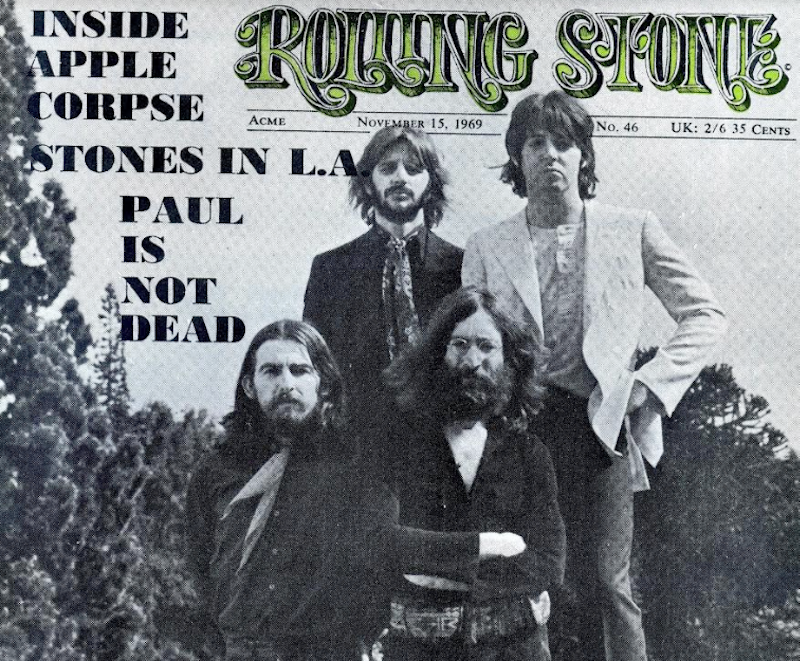

Because for all the boyish self-flattery, buffoonery, drug use, and gauche taste, another side of Jann Wenner is emphasized throughout Hagan’s book: the man was a brilliant promoter in the right place at the right time, hired the right people, and managed to balance his own avarice and the practical realities of running a major newspaper and magazine. Rolling Stone was out of money, in debt, and about to go out of business several times in its 50-year history, but Wenner always salvaged it.

It’s inexplicable, and it’s certainly not the work of some cunning business genius or a genuine 1960s sage, which is no doubt how Wenner would’ve like to have been portrayed by Hagan. Sticky Fingers is the story of Wenner’s life, pot bellies and cocaine addictions and all. I realize that interest in a 547-page book about the founder of Rolling Stone, not the magazine itself, probably isn’t that high, and the book would’ve been a lot less entertaining if Wenner wasn’t such a uniquely fucked-up but somehow talented and cunning guy. At one point it’s noted that Wenner is “unable to feel embarrassment,” separating him from most rock stars, entertainers, and media figures. A slipshod hit job with the stuff in Sticky Fingers probably would’ve been dismissed by most, but the subject spills his own guts, and the anger at his biographer only reinforces the picture it paints of the man.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992