Linda Holmes at NPR is highly dubious about The Washington Post’s recent profile of Chevy Chase. “Is a profile of him at this moment in all of our lives really necessary, though?” she tweets. A second tweet elaborates: “he hasn't done work in a while, and his unpleasantness is well-documented, so I’m just wondering whether it’s productive to keep giving him attention.” Note that she’s doesn’t object to anything in particular about the piece. She’s just leery that it exists.

The Internet is a loose baggy monster, and The Washington Post has shown itself willing to splash out on features. Yet we’re hearing “necessary,” a word normally used when tight limits are around. Decisions about screenplay structure, basement storage, or the family budget are good situations for “necessary.” Likewise “productive” is used for things like offices, meetings, and chicken farms. An article is more likely to be described as informative, revealing, interesting, and so on (or else their opposites). “Necessary” and “productive,” in this new context, strike me as clues. And here’s another: “wondering whether it’s productive to keep giving him attention.” Possibly this business about attention means that Chase wants to read about himself and we shouldn’t let him. Or else it means that the public at large shouldn’t know anything more about the old villain. Either way the idea seems to be that Chase is a problem, and that the article, by existing, makes the problem worse.

That’s the attitude I detect behind the odd word choices: that an article isn’t primarily something produced by some people and read by others, and that instead it’s an allocation of social favor, a dollop of importance that society drops at the feet of some favored subject or another, and that the article’s existence will be good or bad depending on what attitude it amplifies on society’s part. If we already know that Chase is a jerk, this new article exists simply to bulk out the pile at Chase’s feet. We don’t want that because Chase is one of the big bad white guys.

That very last point, the one about Chase, is obviously true. When he was co-star on Community with Donald Glover, Chase made cracks about Glover being black. When Saturday Night Live had a gay cast member, Chase thought it would be funny to weigh him every week so viewers could see if he had AIDS. Now, in the scheme I attribute to Holmes, the big bad white man shall no longer be big—look, no article about him. And society shall be less a thing that belongs to big bad white men, because look, we don’t have to read about this one.

Much as I dislike big bad white men, I find this line of thought to be a dud. I read for myself, and I don’t trust Holmes or anybody else to gauge the final effects. Not that I think Holmes wants to decide what people can read, or that the view I attribute to her is stupid. (During the recent noise about Louis CK, she produced some tweets that are models of incisive commentary.) I don’t even say she’d sign off on this view I present, since I’m the one who extrapolated it. But past that point I dig in my heels. I bet Holmes’ preferred view would be at least a neighbor to the one I describe, whereas my own way of seeing these matters is on a different continent. My further sense is that my continent’s sinking and hers is rising because we live in the latter days.

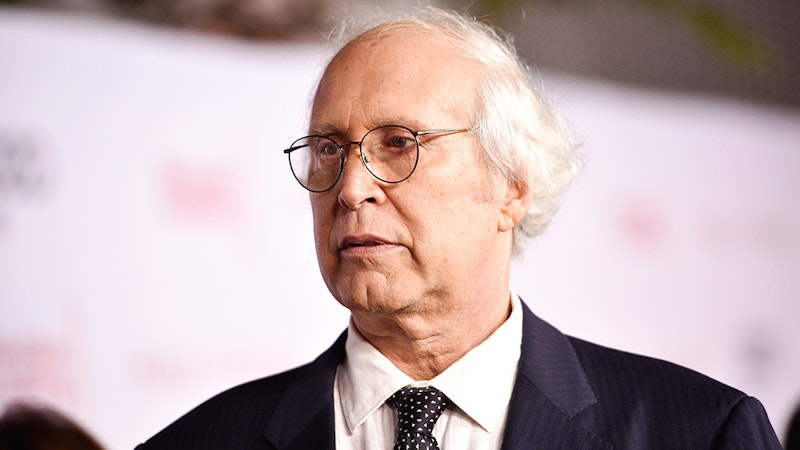

In Chevy Chase’s living room. “There’s a script by an unknown screenwriter. The part he’s being pitched includes all of three lines. He wonders why his manager sent it through.” Here’s a story about Chevy and his old show, Saturday Night Live: “Six summers ago, at his daughter Cydney’s wedding, Chase turned to Lorne Michaels and told him he was ready. He hadn’t been back to host since 1997. It was time.” Punchline: “‘He said no,’ Chase recounts.” From the star’s childhood: “But he lived with his mother, Cathalene, who would wake him up in the middle of the night and slap him repeatedly in the face without explanation.” (Paul Shaffer cracks, “I thought he had gone to Bard, and it turns out it was the School of Hard Knocks.”) Martin Short tells a story to illustrate how huge Chase was back when he was huge (end of 1975, much of 1976). One of Chevy’s daughters says she got fed up with Chase because of his drinking. Now he’s stopped and he’s lost 40 pounds.

The above is from “Chevy Chase Can’t Change” in The Washington Post. Right below the headline: “The 74-Year-Old Comedy Star Is Sober and Ready to Work. The Problem Is Nobody Wants to Work With Him.” The evidence comes down to the Michaels anecdote and the script with the three-line part. Fine by me, and the article’s 4900 other words provide a decent portrait of the jackass in winter. The piece is good reading for people curious about Chase or celebrity life cycles or baby boomer decay or the perpetual retreat into non-being of that dingy golden age, the 1970s. “I'm interested to see where his lifetime of nastiness has come out,” I tweeted, and I stand by those words.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3