Google unintentionally scooped the Smithsonian American Art Museum when it released the full photo archives from Life magazine last year. Now anyone with a mouse can pour through photographic records as far back as the 1860s, but it’s work from the 1930s that trumps the current SAAM exhibit, “1934: A New Deal for Artists,” made up of paintings commissioned by FDR’s Public Works of Art Project. Google’s treasure trove is quick, it’s easy, and it makes the argument that the visual context for this era exists not in painting—which makes up the entirety of the “1934” exhibit—but from other media: photos of endless bread and unemployment lines and a devastated rural America, the work of Walker Evans and James Agee, Woody Guthrie and the folk music movement. (The important exception to this would be Diego Rivera, whose populist murals were made of a purer, more monumental art. His depiction of bankers in line with conquistadors tops any of the pitiful gasps of today’s “populist” movement.)

There is no small amount of immediacy with the subject; the American public is facing perhaps its greatest period of economic unrest since the Great Depression. On the exhibit’s excellent slideshow I posted a question that, in short, wondered how much consideration was given to the current economic crises when planning this exhibit. Ann Wagner, a curator for the exhibition, responded:

The exhibition was planned before the September economic collapse, but only a few months before it when the real estate situation was already very bad. The original concept of the 1934 show had more to do with the 75th anniversary of the Public Works of Art Project, the first of the New Deal art projects. But the museum also planned this show from our permanent collection in order to save money rather than bringing in expensive traveling shows.

[…]

I was very conscious of the parallels between then and now when I was researching and writing the book entries and labels between September and December 2008. But I also paid attention to the many differences between the two periods. I had to do a lot of work, and have a lot of help from librarians, archivists, historians, and curators, before I understood at least some of what was going on in the PWAP paintings. I look forward to learning more from people all over the country.

There is a perfect, if unplanned, introduction to the “1934” exhibit. W.W. Robbins’s “Weathervane/Model of a Cadillac V–16 Sport Phaeton” stands at the end of the folk art wing and just before the secondary entrance to “1934.” It rests a few feet above the average viewer, the detailed vehicle heavy and secure, pointed west. It offers as reductive a metaphor as they come: the automobile as America’s industry headed out to the suburbs and the last remaining swatches of the frontier—now still and lifeless in a climate-controlled museum. If one approaches the exhibit through the main entrance, the first artwork is nearly as painfully metaphoric. Ross Dickinson’s “Valley Farms” (1934, oil on canvas) offers a stark introduction: a small farm is nestled in the foreground against a looming chain of valleys taking two thirds of the image. Two plumes of smoke linger in the foreground and background, presaging an ominous future. This type of basic narrative is found throughout the exhibit, usually with a narrow palette of bright colors and a quaint Americana vocabulary.

According to an employee in the AAM’s bookstore, the exhibit has seen steady—and surprisingly high—traffic. In his own words, he conceded that some the paintings might be considered “boring,” but nonetheless the people keep coming. Some of the pictures are boring, but what perhaps keeps the crowds moving is the overall wash of sentimentality and cohesion found in the paintings, all oils on stretched canvases executed between 1933 and 1934, many in a frame with a PWAP dog tag stamped at the bottom.

And yet there are very few good pictures in the exhibit. By themselves, most of the paintings drown in banal populism—the kind that condescendingly glorifies calloused field hands and ignores the non-white (there are, at most, two or three non-white subjects in the whole room). The exhibit’s tone is schmaltzy in its homage to the working poor and working class, more like a Steinbeck novel like The Grapes of Wrath or Cannery Row than anything else.

A small exhibit on the other side of the museum houses a group of paintings by Edward Hopper and a selection of photographs from the same era (starting in the 1930s through the 60s), exploring the potential—and, I find, highly plausible—relationship between Hopper’s work had with the growth of photography’s canon. Both placed everyday people, structures and objects in subtlety dramatic settings, creating tension and release with placement and composition. Hopper’s “Ryder’s House” (1933, oil on canvas) is a simple painting of a rural house, yet the windows are either shuttered or the blinds are drawn, giving the house a flattened depth at odds with the bucolic prairie landscape.

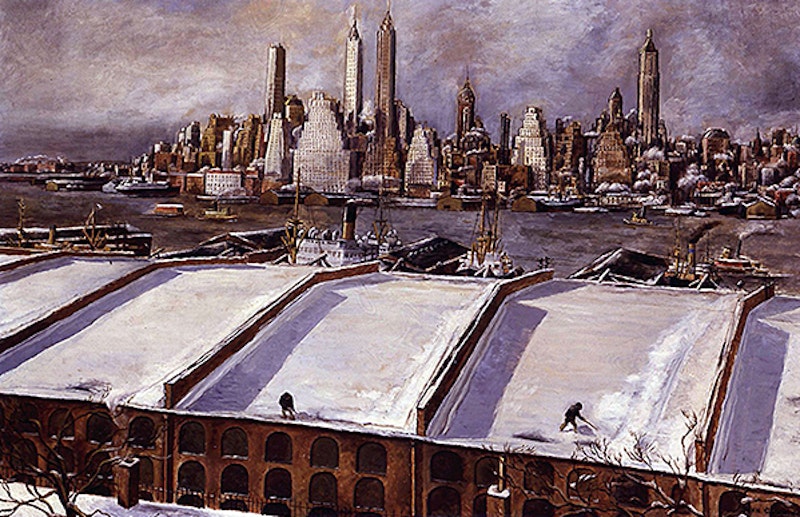

No one is blaming the PWAP artists for not being all Ed Hoppers, Diego Riveras and Pablo Picassos, as there are several wonderful paintings to take in, such as John Cunning’s “Manhattan Skyline” (above; note the use of the snow-filled warehouse in the foreground as a stand-in for rolling fields in a typical landscape); “Underpass—Binghamton, New York” by an unidentified artist, in which the closest lamppost hangs in the air with a spectral quality; Ilya Bolotowski’s “Barber Shop,” which could almost be confused with a lesser Van Gogh; and J. Theodore Johnson’s “Chicago Interior,” which captures, if fleetingly, a healthy dose of the burgeoning bourgeoisie amid the clang of industry.

While the reductive approach is enticing, it’s important to remember the exhibit is not meant to be an important chapter in the art of painting. It is an historical record at its most basic level, and the museum has made a substantive effort to broaden the exhibit’s focus: The aforementioned message board has elicited new information on several of the exhibited works; there is a Flickr group for sharing your own 1930s-era photos; and an interactive map plots the locations of several of the exhibit’s works. It brings to mind a post from Andrew Sullivan, wherein he describes his blog as a “historical document”—not history in the age-defining sense, but as one of many windows for future generations to regard a particular era. The exhibit’s simple, populist drama, then, is given more room to breathe with the help of digital technology. The paintings are elevated by the era’s photography, a foreshadowing of the dominance of digital media today, and the “historical document” grows more nuanced.

Perhaps nuance is what’s missing from the “1934” exhibit. What we see is a flat-lined observation of the era, bravura and desperation all in the same sheen, no peaks or valleys. Julia Eckel’s “Radio Broadcast” is an accidental still-life arrangement of a group of musicians with an almost-religious feel to the composition. It’s a near-perfect inverse to the music that was much more relevant to that time period.

Music plays a much smaller barometric roll today than it did in the days of Tin Pan Alley and gospel, genres that were as important to the communities that fostered them as they were the broader listening public. The Internet, and subsequently social media, offers the largest breadth of dialogue and community building—and is now the new battleground for defending the New Deal. In the future, the available historical documents will fully span all media, providing a multi-dimensional history (with some painful, over-sharing aspects; Twitterati and Facebookers, I’m looking at you). Exhibits like “1934” will look even more one-dimensional. This is not to say the show isn’t worth your time. There is much to take in from the exhibit’s array of landscapes, cityscapes, calm industries and developing urban vocabularies. Take your parents, take your kids, and look forward to future backward-looking exhibits that will better transport you.

Hard Times at the Smithsonian

The American Art Museum's new exhibit, "1934: A New Deal For Artists" highlights some of the best government-subsidized work from the Depression era.

John Cunning, "Manhattan Skyline" [1934]