Vilnius sits like a posy pressed between the pages of a worn copy of Das Kapital, decaying in the south-eastern corner of Lithuania. Lacking Riga's size or Tallinn's medieval beauty, it nonetheless has a certain liveliness absent in its sister capitals, a curious funkiness, where the baroque facades of Rennaisance churches share space with the crumbling remains of millennia-old pagan altars; where sprawling communist architecture has been converted to underground punk clubs; and where the world's first and only Frank Zappa memorial monument is far from the hippest of the metropolis' wonders.

But then any nation with a history as varied and fascinating as Lithuania would create a centerpiece as unique as Vilnius. At one point encompassing a territory stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black, the hardy and war-like precursosrs of the modern Lithuanian people prayed before the undying fires of their forest altars for thousands of years, before the Teutonic forces gradually overcame it during the centuries long ''Northern Crusade.'' In the years before their absorption by the German-Christian forces, the Lithuanian court was a model for tolerance and learning, offering religious foreedom not only to Pagan and Christian but even to the despised Hebrews, allowing for the building of synagogues and theological instruction while the Catholic majesties Ferdinand and Isabella were destroying the golden age of Andalusian Jewry in an orgy of blood and fire.

An alliance with Poland led to the high-point of Lithuanain national power, before its gradual dissolution by hungry neighbors led to a long decline. Like the nations surrounding it, Lithuania suffered terribly during the 20th century, briefly enjoying the flush of autonomy before being ravaged by the Nazis and subsequently being placed beneath the ministrations of the Soviet Empire. The first nation to declare freedom from the U.S.S.R., Lithuania has spent the years since struggling to overcome the crumbling infrastructure and retarded standards of living common to former Soviet satelites, and the inevitable brain-drain that such conditions spur.

For all the historical cruelty they've endured, Lithuanians generally maintain a gregarious attitude unshared by their Baltic neighbors, and the black humor that has long been the only recourse open to them. My hosts are a professional couple in their early 20s, the missus a film-translator, the mister a web-developer. In the states their intellect, wit and taste would place them firmly in that blurry spot between yuppie and hipster, living in an IKEA-furnished apartment in an up-and-coming neighborhood of a major American city. Here they live, like virtually everyone else, in a rundown blockhouse, with few of the 30-year-old Soviet-built amenities functioning, and none operating with absolute precision or regularity. In the small lot outside cars are parked in every spot an automobile could possibly be wedged, overflowing the asphalt onto sidewalks and gardens. "When they were building these,'' my hostess explains, ''they never thought more than one or two people would own a car.''

Though they scoff at partriotic talk and scorn the incompetence of their goverment, their pride in their homeland still bleeds through. After listening to the remainder of my itinerary my hostess shakes her head with dissapointment. ''These are shitty countries,'' she says, years of chain-smoking combining with her Baltic accent to make her sound not entirely unlike Natasha from Rocky and Bullwinkle. ''Why do you want to go to all these shitty countries?'' She ashes her Winston Silver in a jar now emptied of homemade gerkins, scratching at the chin of her massive black Newfoundland. ''Lithuania is also a shitty country,'' she acquiesces, then points the glowing tip of her cigarette at me with mock seriousness. ''But it's the best shitty country.''

All of Vilnius seems suffused with this spirit, the hard won pride of a survivor, who, knowing her scars are too recent to be hidden, dresses them up as a mark of honor. The city's obvious attractions, primarily its gorgeous Old Town and many leafy parks, are of little interest to the local population. My hostess and her friend flip through my guidebook and laugh uproariously. ''I would never go to any of these places,'' she says, pointing to the drinking section. One in particular catches her eye and she quotes the name in disbelief. ''This is the worst bar in the world.''

Her friend, Eglė, nods with a sad smile, as if afraid to hurt my feelings. ''Only fat Germans go there.''

Not wanting me to leave Vilnius thinking it contains nothing but churches and meaty Bavarians, Eglė agress to take me on an alternative tour of her city. She advises me to wear boots, takes me to a nearby grocery store for beer to sustain us on the road, and starts us off on a trek through her hometown that Frommer's would likely not approve of.

Eglė's suggestion for rigorous shoewear proves prescient at our first stop, which she describes as being ''probably the worst ghetto in Vilnius.'' Rows of corrugated metal shacks sit interspersed with communal wells, resting incongruosly close to a thriving business district, the skeletons of skyscrapers being rapidly erected. ''The ground is worth a lot of money,'' Eglė tells me, ''but most people won't sell.'' Looking around at the third-world conditions I appreciate the local's sense of pride, if not their business acumen.

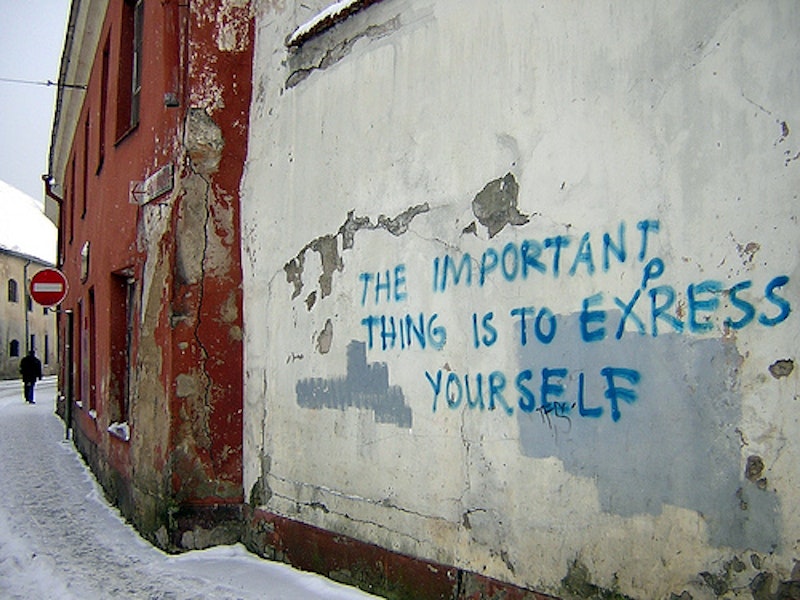

Next up is a mammoth concrete infrastructure lacking any outer development. What would have been a huge (though, I would guess, very ugly) Soviet hotel has become a canvas for the local artists collective talents, an opportunity they have afforded good use of, huge graffiti murals of all styles and subjects. More locations follow, an abandoned concrete factory nestled amidst an old-growth forest, a crumbling cemetery, the worn remains of a pagan chapel atop a high hill east of the city.

But the centerpiece of our tour is the Republic of Uzupis, a neighborhood of artists, poets and, as my guide describes them, ''friendly drunks'' lying east of the Old Town proper. Lacking the anarchistic freedom of Denmark's Christiana, Uzupis feels less an anomaly than that town, and a more natural outgrowth of Vilnius' innate character. Punks sit by the river watching painted waterwheels spin leisurely, and Lithuanian hipsters meander between art galleries. On a small side street, a dozen mirrored plaques display the contitution of Uzupis, 41 regulations written in Lithuanian, English, French, Hebrew and a half-dozen other languages, promising to lead the all the world to paradise were we to abide by them. My personal favorites are 13 (A cat is not obliged to love its master, but it must help him in difficult times) and 22 (Everyone has the right to encroach upon eternity).

Heading out of Vilnius the next day I crossed over the Green Bridge, the main pedestrian thoroughfare in the center city, capped at each end by Soviet-era statues presumably not demolished by the populace post-independence because they are such perfect examples of that most hideous style. Staring up at the square-jawed youth with hammers and manly-looking woman holding sheathes of wheat wide enough to cripple a tractor, I was struck by how foolish the Soviest were in seeking to stifle the impulses of the vividly colorful Lithuanian people and replace it with such barren monstrosities. Left to their own devices, the citizens of Vilnius erect multicolored stone eggs in their city squares, and elevate horn-blowing angels above beer-sprouting well-springs, yet Stalin and his ilk thought to pave over this ebullience with gravel and concrete.

But in time these scars will fade, and the remnants of the evils forced upon Vilnius and her people will be nothing but a grim memory, and the city will be again left as it is naturally—vital, free and funky.